Andrew Rosthorn on stories of the NW, the slave trade and the problem of unhelpful introspection

A ship from 1619

Perhaps the origins for the Guardian’s strange introspection over its founder John Edward Taylor’s links with slavery appear to begin in the USA. It seems the motivations behind this repackaging of history are linked if nothing else.

A particular example is the 1619 Project, published in August 2019 by The New York Times to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival in Virginia of an English ship called White Lion?

The White Lion’s captain traded thirty slaves captured at sea from a Spanish ship bound for Mexico by exchanging them for ship’s stores supplied by the English colonists of Virginia in August 1619.

English lawyers call it nunc pro tunc, Latin for ‘now for then.’

Nikole Hannah-Jones, a staff reporter on the New York Times, won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her ‘sweeping, provocative and personal essay for the ground-breaking 1619 Project, which seeks to place the enslavement of Africans at the center of America's story, prompting public conversation about the nation's founding and evolution.’

But by December 2019, the New York Times Magazine had published a letter from five eminent historians, accusing the authors of the 1619 Project of ‘displacement of historical understanding by ideology’, the Gray Lady of Eighth Avenue especially for suggesting the American revolutionaries of 1765 were fighting Britain to protect slavery.

One of the five historians, Professor Sean Wilentz of Princeton University, wrote in the Atlantic Monthly that ‘no effort to educate the public in order to advance social justice can afford to dispense with a respect for basic facts.’

The New York Times journalist Bari Weiss resigned in 2021 from the usually sober-sided newspaper. Ms Weiss complained about ‘activist journalists who treat the paper like a high school cafeteria.’

When Nikole Hannah-Jones was accused of fomenting ‘rage, polarisation [and] distrust’ by her journalism, she told CBS News that “All journalism is activism.”

“We have to try to be fair and accurate. And I don't know how you can be fair and accurate if you pretend publicly that you have no feelings about something that you clearly do.”

Presentism = moral complacency and self congratulation

The New York Times was also accused of ‘presentism’ which is defined by Wikipedia as ‘a pejorative term for the introduction of present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past’ - pretty much what Denys Arthur Winstanley wrote in the UK in his 1912 Lord Chatham and the Whig Opposition: ‘Nothing is more unfair than to judge the men of the past by the ideas of the present.’

Lynn Hunt, Eugen Weber Professor of Modern European History at UCLA in California, wrote in 2002: ‘Presentism, at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation. Interpreting the past in terms of present concerns usually leads us to find ourselves morally superior; the Greeks had slavery, even David Hume was a racist, and European women endorsed imperial ventures. Our forbears constantly fail to measure up to our present-day standards’

While Nikole Hannah-Jones was declaring in New York that ‘all journalism is activism’ seven historians in Manchester, including Professor Matthew Smith, director of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership at University College London, and Matthew Stallard, a researcher at UCL, were working on a 12-month ‘public history collaboration’ with Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum known as Global Threads.

The Gobal Threads team conducted ‘original research into Manchester’s buildings, locations, memorials and museum objects to draw out new and previously under-described stories of lived experience, resistance and solidarity in relation to colonialism, enslavement and the city’s cotton economy.’

In April 2023, the Guardian asked Matthew Stallard to write the introduction to their ‘visual exploration of historical Manchester’s rapid growth into a ‘shock city’ – and how slavery was key to the emergence of Cottonopolis.’

Time for some Latin lessons

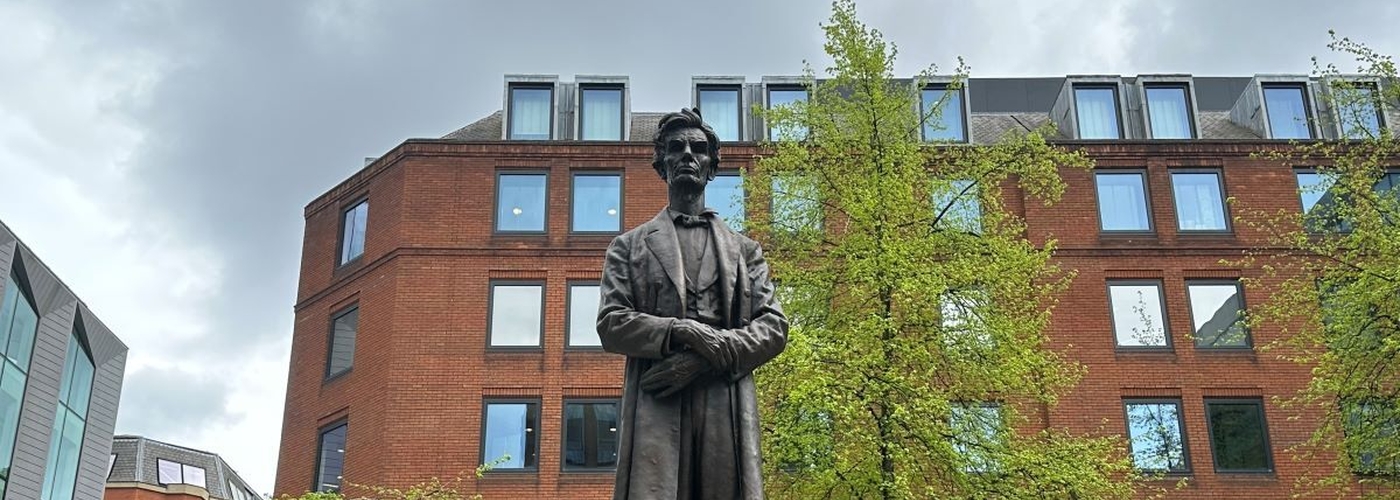

One of the Guardian’s sub-editors also conjured the now renowned 19 April 2023 headline asking whether the sailing ships on the crests of the city’s two world famous football clubs should be removed as ‘emblems of a crime against humanity’.

Under the strapline‘Abandon ship: does this symbol of slavery shame Manchester and its football clubs?’ Simon Hattenstone offered an excellent example of presentism, ‘introducing present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past’ and surely unfair for the reason given by Winstanley back in 1912: ‘judging the men of the past by the ideas of the present.’ Jonathan Schofield vigorously responded on these pages defending the ship, its symbolism and the men who had caused it to appear on the coat of arms.

Lawmakers have the power to make laws to correct unjust situations by drafting a new law with retrospective application. English lawyers call it nunc pro tunc, Latin for ‘now for then.’

Nunc pro tunc might be valuable in a parliament or a courtroom but it must surely be verboten to historians and even dodgy for the writers of historical novels. For the Guardian and the New York Times, nunc pro tunc on slavery has proved to be a dangerous drug.

It’s not as if the facts of the world-wide effects of slavery were unknown until recently or that eighty per cent of the cotton piece goods traded in the world were traded by the 11,000 merchants of the Royal Exchange in Manchester.

In the hundreds of thousands of words published this year by the Guardian and the UCL Legacies of British Slave-Ownership website we are not told the unassailable fact that in 1785, when Peel, Yates & Co of Liverpool imported the first seven bales of American cotton ever to arrive in Europe, human slavery had existed on this earth for 11,000 years.

We are not reminded by the Guardian that in 1785 the United States of America had been politically independent for twenty years or that without using a single pound of American cotton Lancashire had been ingeniously producing and exporting high quality textiles on high wages for 200 years.

And now time for some history

You will not read in Global Threads about James Barlow, 1821–1887, the son of a Tottington handloom weaver and builder of the Albert Mill in Higher Bridge Street, Bolton, where thousands of spinners and weavers turned out the best cotton blankets, bedspreads, satin quilts and ‘Osman’ Turkish towels that money could buy.

The source of Barlow’s wealth and the relatively high wages he paid his workers was American slave-grown cotton. It was the only usable cotton available in large quantities after the East India Company had restricted supply from India. When the supply from America was cut by the Civil War, the Lancashire mills shut down.

Barlow was a profoundly moral person, a devoted and influential Methodist, a president of the British Temperance League and a lifelong campaigner against slavery. He was elected mayor of Bolton after the Cotton Famine.

The Cotton Famine hit North West England in the winter of 1862, the second year of the war and largely as a consequence of the war although there were other factors. The slave-owning Southern states were refusing to ship their 'Middling Orleans' short staple cotton to Liverpool and warships from the Northern states were intercepting blockade-runners loaded with 'Sea Island', the long staple cotton on which the fine spinners of Lancashire depended. Both sides in the Civil War were putting pressure on the British government by starving the people of Lancashire. Half a million workers were on poor relief. Half the spindles and half the looms were idle. In Preston, 42 per cent of mill hands were unemployed for want of cotton.

Karl Marx had warned in the New York Daily Tribune on October 14, 1861, that "As long as the English cotton manufacturers depended on slave-grown cotton, it could truthfully be asserted that they rested on a twofold slavery, the indirect slavery of the white man in England and the direct slavery of the black man on the other side of the Atlantic."

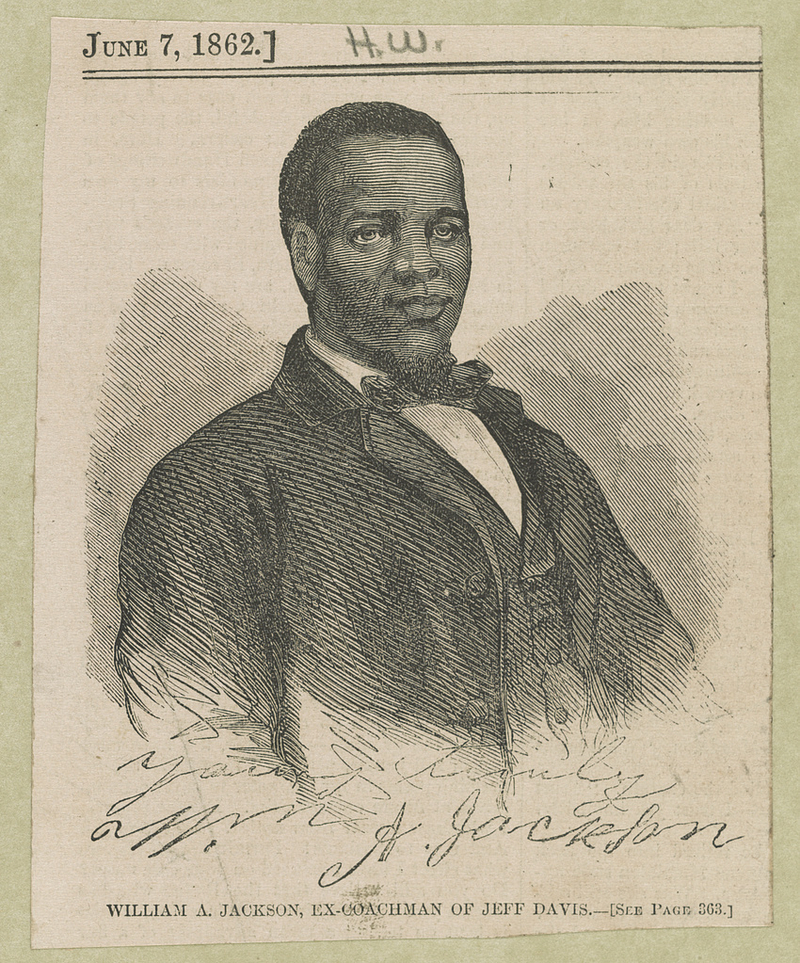

Back to James Barlow. In February 1863 he brought an escaped American slave to stay at his new home, Greenthorne, near Edgworth, and arranged for William Andrew Jackson to speak to two thousand people packed into one of the new temperance halls in Bolton.

Barlow outlined Abraham Lincoln’s case for the civil war then introduced the black man who had been rented out by his owner to work as a coachman for the rebel Confederate leader Jefferson Davis. Jackson told the audience how the Confederate president had ignored the presence of a slave when discussing war plans with his generals. This arrogant error was recounted recently in the CIA journal Studies in Intelligence.

When Jackson made his dangerous break for freedom across the battle lines in Virginia in 1862 he carried to General McDowell of the Union army valuable military information memorised by listening to the plans of the Confederate generals. McDowell telegraphed the War Department in Washington and Jackson became the most hunted black man in America.

Alan Rice, reader in American Cultural Studies at the University of Central Lancashire, said Jackson was a “great speaker and used his speaking skills to rouse people into supporting the anti-slavery northern states of America. He was widely praised by Lancashire workers.”

Greenthorne, a safe house on the Lancashire moors for a fugitive American slave, became 68 years later a safe house for Gandhi. The Mahatma was under relentless attack from the British newspapers for organising a boycott of Lancashire cotton cloth. He had been released from prison to attend the Second Round Table Conference in London on the future of India. On a secret visit to Lancashire in 1931 Gandhi stayed overnight at Greenthorne at the invitation of James Barlow’s humanitarian granddaughter, Miss Anne Barlow.

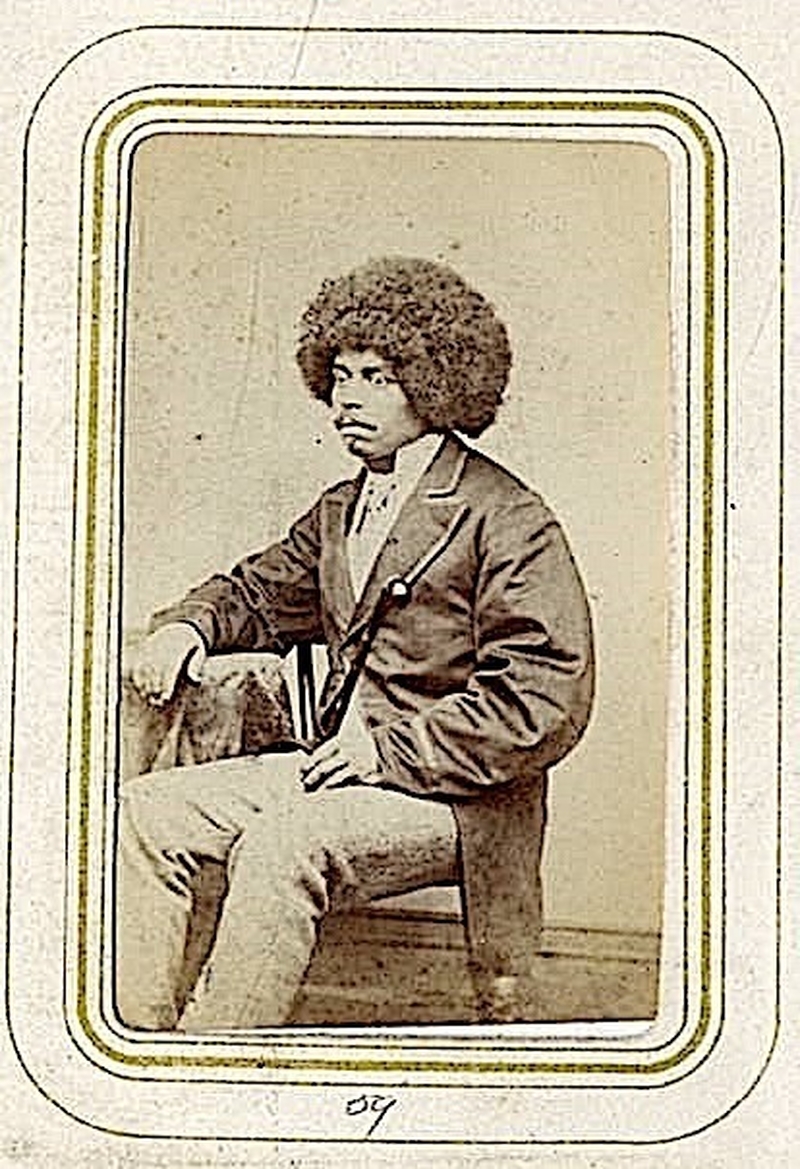

The escaped slave James Watkins was living openly in Manchester in 1861 when the census showed that he was a “lecturer on slavery” at 74/73 Piccadilly. He had escaped in Maryland, guided to relative safety in Connecticut by members of the Underground Railroad, then fled to Manchester to avoid re-capture by slave catchers under the notorious 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

In September 1866, the year after a former Confederate secret agent assassinated President Lincoln, another escaped slave, James Johnson, was working as an iron striker at Dawson & Stanier’s Flat Top Foundry in Oldham. Later he worked for Platt Brothers and campaigned in Lancashire and Yorkshire as an evangelist preacher. In 1869, he married Sarah Preston, a mill girl “through whose instrumentality and patience I have acquired the blessed boons of being able to read and write.”

After Sarah died James Johnson married Mary Ann Cook. Their daughter published a 12-page pamphlet after he died in 1914.

The Life of the Late James Johnson (Coloured Evangelist). An Escaped Slave from the Southern States of America. 40 Years resident in Oldham, England; recounts the life of a man born into slavery in North Carolina in 1847, with no knowledge of a mother or a father and sold for 825 dollars to a plantation owner. A single copy of Johnson’s autobiography survives in the Oldham Local History Archive.

There are so many stories to find on this subject with no nunc pro tunc involved, just history plain, as a matter of record.

Andrew Rosthorn is a veteran news reporter, born in Yorkshire and now based in Lancashire. After reporting the Irish troubles in the early seventies for the Daily Mail, he worked on hard news for the Daily Mirror, Sunday Mirror, the Independent and the Independent on Sunday.

This is a freelance opinion article.

If you disagree or agree we’d like to hear from you. We want a range of opinion on Manchester Confidential. As we said here in January: ‘We have a policy of freedom in writing and do not hold any doctrinal, political or ideological position. Nothing is cancelled and all sensible stories will be considered. Of course, writers must provide high quality, punchy and grammatically tight content.’ Try us, send us ideas, get a voice.

If you liked this story read these:

Manchester architecture part two

Hong Kongers in Manchester

Mrs Beeton and pigeons transmogrified

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!