This is a long article that covers several different key points of Manchester's governance in 2013. For this reason we've split the story into chapters, in case you want to attack it piecemeal.

Chapter One: Of Consultations And Foot Stamping

"OF course you can always do consultation better," says Sir Richard Leese. "To say everything’s always perfect would be a bit daft. But also, I’ve got lots of experience of people who apparently didn’t notice the consultation first time round, even though they had leaflets about it, or spoke to their neighbours about it, and then something happens and they say, ‘Why wasn’t I consulted?’”

One of the duties we have as councillors is to represent those people who, for whatever reason can’t come and lobby for themselves.

The Council Leader and I are sitting in his office, a couple of floors above Princess Street, in the grandest Victorian town hall in the nation.

There's Leese's desk under the window, and a boardroom-like table closer to the interior wall. Against a chimney breast, carefully placed, is Sir Richard's bicycle, the helmet slung rakishly off the frame.

There are books scattered about, papers too, it's not the neatest office but not the messiest either. It's a working space.

Surprisingly there's no press officer sitting in the interview. It's just the man and me with one of the Confidential interns, Jo Milligan.

"But that's one of the problems," I say. "Residents seem to feel, whether it’s to do with libraries, schools, swimming pools, parks, that the decision’s been made and the consultation comes in afterwards. Consultation is in effect just a cynical game."

"First what people need to understand is that they have to have a proposal to consult on," Leese says flatly. "The library and pool debates came from a proposal subject to statutory consultation as part of the budget process. This comes with an evidence base to support it and we build a proposal that’s based around that, then we go to consultation."

"So are people wrong to feel they are being told to accept decisions and not being given time to object," I say.

"Look, I think it’d be a sad situation if no-one cared about their local facilities. The fact that people care about them and want to do something about them is a good thing. But it’s equally the case we can’t sustain everything we’re doing at the moment as you can only pay for things if you have the money."

Sir Richard Leese pauses for a second and there's a note of impatience, even irritation, in his voice.

"There are many instances were people were previously informed or consulted about an issue and didn’t bother about it. A favourite of mine is when somebody who’s been involved in a consultation is unhappy because the outcome is different from what they want. Then they always say the consultation process was flawed."

"Remember with many of the these issues," he continues, "people would have known about them because they were discussed in the last round of cuts. I know it’s something you’ve raised in the original articles around Alexandra Park (click here), but let’s take that as an example of the process.

Park protesters keeping watch for the woodcutters

Park protesters keeping watch for the woodcutters

"From our side there's been consultation and involvement with local members, ‘friends of’ groups and other parts of the local community. Probably there have been about four or five years of discussions and various plans so this was not something that happened overnight. There were also very public bids to English Heritage to consider funding, there were the planning applications, which again are very, very public."

Leese pauses and looks briefly around the room.

"We've been very open. I'm not sure how people can claim we haven't been open enough. But there's something we're missing here."

There is a real obligation on us, a political one, as councillors, to be the advocates for those people.

He shifts in his chair, and leans forward onto the table, his hands clenched.

"Aside from libraries and parks and pools there is another role in terms of our politics as a Labour Group. It concerns whole areas where we are making fundamental changes around social care. This is the biggest chunk of our budget, we’re taking back forty-odd million pounds over three years with the cuts, and trying to make the best of it. That's hard.

"Yet I’ve not seen anyone out there with a placard or demonstrating about this. Children in care aren’t going to demonstrate, people with learning difficulties aren’t, people with mental health issues are unlikely to, old people suffering from dementia aren’t either.

"One of the duties we have as councillors is to represent those people who, for whatever reason can’t come and lobby for themselves. A lot of those don’t vote either but there is a real obligation on us, a political one, as councillors, to be the advocates for those people. Some things are invisible to all except the direct recipient of that service and it’s an absolutely crucial role for us to understand that as councillors."

“And aside from consultation, if city residents want the council to change policy, reverse decisions what should they do?" I ask. "After all Confidential had a petition on the changes to on-street parking in the city centre during early evenings and on Sundays a couple of years ago and that was ignored."

“First, we do reverse or amend decisions as the current consultation process has shown (click here). This may not have happened with your parking objections. In the end as the elected council we didn’t agree with your position. As it turns out I have to say the evidence on the parking would demonstrate that we’re not 100% right on it which is why we’re refining the policy.”

The refinement which happened on 4 April, after the interview, was another consultation about whether charges should rise in key areas of the city centre, with a small fall in peripheral areas (click here). The extension to on-street car parking charges it seems is a decision that won't be reversed.

Chapter Two: Of Chief Executives And Decision Making

BEING open when it comes to democratic accountability is the whole point of the interview.

In other words who runs the city and how is it run. This arose from several articles we've run recently.

Every year, the Chief Executive will be given the election manifesto and told, 'That’s what we’re delivering over the next twelve months'

There was a feeling that something had broken in the Town Hall, and not just with the Alex park tree-folk, but also with many Mancunians about cuts and their imposition.

Several readers and friends of Confidential were wondering whether councillors had become the mouthpiece of bureaucrats, selling the latter's decisions to the public, when of course the elected representatives should be telling the civil service of Manchester what to do. Are the bean counters ruling the roost?

"Talk me through how policy decisions are made in the city from idea to delivery," I ask Sir Richard.

"Let’s start with the biggest decision, the budget," says Leese. "We were given a settlement from government where we had to make savings of £170 million by the second year of a two year period. The starting point was a principles paper which I wrote.

“The principles paper was discussed and agreed by the majority elected group on the city council - the Labour Group. I then gave the principles paper to the chief executive who distributed it to the strategic management team. They then started working on proposals in discussion with the elected executive members."

"So it all starts with the elected representative, you perhaps, through the Labour Group, the majority power base at the moment?” I say.

"Initiatives can start in all sorts of ways,” says Leese. "Every government brings in new legislation, a lot of which will have an impact on what we do as a local authority. It will require us to do things or stop us doing things we don't want to do or want to do. We have to come up with solutions.

"It’s as likely to be a council officer, unelected, that sees a way through as much as an elected member, and they will bring it into the discussion. Ideas originate in all sorts of places and it’s certainly not the case that elected members have a monopoly on ideas."

Sir Richard Leese, pauses and opens his hands wide.

"I suppose that at its simplest the process is this: officers advise, members decide, officers implement, members hold to account. That’s the cycle."

Just as it should be. "How are the roles between you and the Chief Executive Sir Howard Bernstein, divided?" I ask.

"Responsibility for economic development in the city, political responsibility, is roughly divided between myself and the two elected deputy leaders,” says Leese. “I lead on major economic development projects and external relationships, Sue Murphy does skills and local enterprise, and Jim Battle covers regeneration and housing. You could argue that transport and other things are in there as well but by and large we share those economic responsibilities."

"And your relationship with the Chief Executive?"

Sir Richard Leese says: "One of our priorities we established for the budget was to continue to support job creating growth. In the current climate, knowing that we had to make big cuts, we asked the Chief Executive to do a piece of work.

"What we wanted to look at were all the relevant elements of the city council and our partners playing a significant role in supporting economic development and then make sure we use resources in the best way.

"We tasked the Chief Executive with doing that job. He gets other officers to contribute and comes back with a paper. We then sit down and have a discussion with him and other senior officers and say, ‘Well, we agree with that, not sure that’s strong enough, we’d like to see more evidence for that and can we get a revision of this.’ When we think it’s in the right shape it ends in a report that goes to the council executive. Then it gets complicated."

"How so?"

"The delivery is the complicated part," says Leese. "Every year, the Chief Executive will be given the election manifesto and told, 'That’s what we’re delivering over the next twelve months'. It’s actually when you get into how do you do it that it gets more complicated and it’s an iterative process, a process of discussion and debate, to get to the right solutions with the questions we’ve asked. It can take a while."

"And openness generally?" I ask. "Talk to people in property and there’s city chatter over how major developments in the city are awarded and how the architects who build them get the job. There’s a feeling that there’s a sort of 'we've been to MIPIM' club of winners. (MIPIM is the international property market exhibition held in March in Cannes.)"

But if there is anything like that taking place in city developments, the Council Leader denies it vigorously.

"There's nothing of that nature going on. Absolutely not. It may be that some firms do better than others because some are simply better than others.

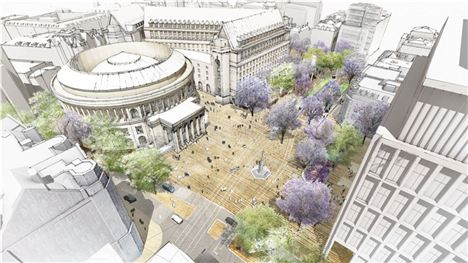

"It’s worth bearing in mind that the overall contract for the design of the civic quarter public realm, St Peter’s Square, Library Walk, the whole lot, went to a Munich-based practice, Latz + Partner, through an international competition. Another big city centre contract, the new cultural centre on First Street, Home, went to a Dutch company, Mecanoo.

"In terms of local architects, I can imagine some of them might make a complaint, but the processes as I've stated before are open."

Chapter Three: Of Councillors, Low Turn-Outs And State Of The City

“FOR a democracy to function representatives have to stay in touch with their communities? How are councillors doing this? What about writing into a councillor's duties, something like an obligation to go 'on the beat' so every week they have to spend time walking their ward?” I ask.

“We spend a lot of time knocking on people’s doors, not saying will you vote for us, but saying what issues concern you, what’s important? As councillors, we all live in the city, use it. If I go in The Cleveland (a pub in Leese’s Crumpsall ward), I’ll find out what’s important to people and the nearer it gets to closing time, the more likely people will want to tell me," Leese says with a smile, not taking up the suggestion of 'the beat'.

"If I’m in Tesco or Sainsbury’s I talk to people. A few years ago we asked people what their concerns were and matched them with what councillors said were key local issues. There was an almost 100% correlation between the two. People knew their patches. We have 96 councillors in Manchester and very few councillors are lazy in terms of doing their basic ward work – and that goes for all political persuasions.”

The fairly obvious thing here is that some people will say, 'Well, we don’t bother voting because it doesn’t make any difference.' Well, I think they’ve just found out that it does make a difference.

As he’s talking I try to remember the last time a councillor knocked on my door. The far side of never seems about right.

But then I live twenty seven metres over the Old Trafford border, off Upper Chorlton Road. Maybe City of Manchester councillors work harder than Trafford ones.

To test this I ask ten friends who live within the city boundaries about their relationship with councillors and not one can recall a conversation with a councillor or a knock on the door from them outside election time. Not one can even remember the names of their local representatives.

“What about openness and you as the Leader?” I ask. “You have your blog, but recently I was in Washington DC and visited their City Hall. Whilst I was there the mayor did a live ‘State of the City’ address on local TV and via various digital media. It was powerfully delivered. Meanwhile every two weeks he also has a question and answer session with the media. What about you doing something similar?"

“We’d have to have a local media wouldn’t we?” says Leese with a cheeky laugh. Anybody who knows the man, who's sat at public debates when he's been on the panel, knows that Leese has a good line in dry wit, often with an edge.

He may have a point about the media, us, though.

Since the digital gauntlet has been thrown down, countless journalists across the mainstream media, particularly in the MEN and the other regional press, have lost their jobs as traditional advertising revenue dries up. Even the number of BBC local newsgathering bods has declined. The new media are building to be in a position to fill the gap, but nobody's fully there yet.

This is a problem. And Leese knows it.

Official processes, local and national governance, the law, the police always need scrutiny. Jeremy Bentham put it best in the 1840s, 'Publicity (we'd call it the Media now) is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion, and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps the judge himself, while trying, under trial.'

Back in the interview, Leese says, "An active media is good for democracy so I agree, there’s no problem with the ideas from Washington. It’s worth having a go. I’ll try anything which engages more people, if it makes them aware of what's happening in the city."

Looking down on the Town Hall from City Tower

Looking down on the Town Hall from City Tower

"The biggest threat to local democracy is surely from low levels of voter turnout," I say. "I've talked to protesters over city council policy, and come across many people who haven’t voted for years in local elections. What's interesting is people will take a position on closure of a baths, a library, on council services in general, without having bothered to vote in local elections. Is there a disconnect growing between council and, let's say, self-disenfranchised residents?"

"The local election turnout last year was higher than it was five or six years ago so we’ve got a slight improvement. It’s about 30%," says Leese.

"That's still pathetic by any measure, and hardly shows trust in the council," I say.

"Of course I’d like it to be a lot, lot higher," says Leese. "The fairly obvious thing here is that some people will say, 'Well, we don’t bother voting because it doesn’t make any difference.' Well, I think they’ve just found out that it does make a difference. It’s whether people will learn from that is the interesting thing."

"Possibly people who protested at the cuts and those who don't vote are saying they think that councillors who should have represented them would always side with the official council decision so what is the point?" I say.

"Councillors in the Labour Group will tend to go with the Labour Group decision but don’t forget, as part of the process, unlike Westminster, we have internal democracy," says Leese.

"So the decisions that the Labour Group makes on the budget through the council are voted for by the Labour Group so it’s not just me or the executive members leading this. We’re not like the cabinet in London saying this is what we’re doing and the whips whip them into place."

"Are you surprised people aren't protesting more across the city given the scale of the cuts?" I ask.

"I suppose I am," says Leese with force. "The level of protest at the moment is not a patch on what it was twenty or thirty years ago. I can remember a period of time in the eighties when we never got through a council meeting without having to throw everybody out, every month.

"Protest is normal. It is part of the democratic process. It’s not something separate to it. It’s the key element of an open, democratic process that people can come to our committees, can come to the council and tell us 'We want you to do this. We’re angry about that. You don’t care about this.'”

"Earlier today, where you are sitting, I had a group of mothers with their babies from a parent and baby group in Levenshulme come to see me about their concerns. I listened to them of course, and that gets into your way of thinking about the city. I think that’s a healthy part of the process."

"But the process needs voters," I say. "Democracy is about protest but it's also about being part of the mechanism. If in Manchester we have a permanent Labour majority then clearly people become apathetic about their electoral voice being heard. Is a de facto one party state healthy?"

"We're not a one party state. There are Labour and Lib Dem councillors. To say that is wrong. But you have to understand that this is bigger than just a Manchester issue," says Leese. "If you look at voter turnout across Europe, it has been declining since the 1950s. Even in places with compulsory voting the turnout has gone down."

Chapter Four: Of Brave Ideas, Excitement And The Problem Of Local Government

"HOW would you reverse low electoral turnout?" I ask.

"Two points," says Sir Richard Leese. "First, we need elections to be competed. If you study voter turnout in Manchester, where you get the highest turnout is where they are most fiercely competed, and that's down to our opponents as much as the Labour Party. The electoral process needs to engage interest. It needs something to draw people in."

With services and welfare comes social responsibility is the message. Just because you pay a council tax doesn’t mean that you offload everything else to agencies supported by that tax and the many other taxes.

That's very true. But the City of Manchester can't escape its history.

As a previous Council Leader, Graham Stringer has pointed out on Confidential, the broad mass of the population within the city boundaries is naturally Labour voting, due to the postwar movement outwards from the city centre to neighbouring Greater Manchester boroughs.

What is perhaps needed electorally is a party that might compete with Labour. Since the Conservatives haven't a chance in Manchester, then that has to fall to the Liberal Democrats, but they continually fall short. Who will fill the void?

Politics aside, the nature of local governance creates apathy. It appears so committee heavy, a morass of words and slowly slowly catchee monkey. It doesn't generate excitement for the general population until it digs them in the ribs through cuts or crisis. Thus protest - not voting - appears the best way to get a voice contrary to council policy heard.

"And the second point?" I ask.

"We have also seen a cultural change," says Leese. A lot of people will now effectively behave as consumers rather than citizens. I think that requires a deeper challenge."

"How deep?" I say "A change in the way many in society think?"

"Very much so," says Leese. "If you look at the principles underpinning the budget process in Manchester we’ve been clear about this. We’re saying that in our communities, if they’re going to survive and thrive, then the people in those communities are going to have to start taking more responsibility for themselves. We have to cut the dependency on the council, change the relationship between the council and the citizen.

"It starts with simple things. If somebody’s got a crisp packet on the pavement outside their house, instead of asking the council to come and clean it up, they go and pick it up themselves. This is something thirty or forty years ago, people would have done automatically, rather than complain to the council and ask for a street cleaner to be sent. People need to sweep the front of their properties, look out for problems in the area, and actively work to make it better."

I draw in breath. This is obvious, goes without saying, it's just I haven't heard it too often from local politicians. Labour ones anyway.

In my mind's eye I recall all those statues such as that of John Bright, and other 'self-help' Victorians, in Albert Square in front of Manchester Town Hall.

These are not maybe the type of person Sir Richard Leese would want to be associated with, but he’s saying something similar.

With services and welfare comes social responsibility is the message. Just because you pay a council tax doesn’t mean that you offload everything else to agencies supported by that tax and other taxes.

I turn my head to look through the windows above Princess Street and in the milliseconds of the pause in our conversation run through the reasons for how we got to such dependency on local and national government.

In doing so I get lost in a maze of issues including a breakdown in sense of identity and common purpose, the atomisation of society with technological advance, the welfare state, and surely the worst evil, the true cause, lack of meaningful jobs and long-term unemployment, resulting in anger and alienation.

Stunned by the scale of change implied in the Council Leader's words I stutter out, "But that’s so beyond what the council can do, that’s a huge social change you’re calling for. The ripples extend far beyond Manchester."

Sir Richard Leese, Leader of Manchester City Council, leans back calmly.

"It is massive. But it needs to happen. It won’t happen overnight, of course, but it’s very explicit in the budget proposals. In order to deliver the sort of Manchester we want, we need behavioural change. Behavioural change takes time.

"Our citizens have got to start acting more as citizens and less as consumers. We have to start this process now, and we’re actively looking at ways to bring that about in a meaningful way from the earliest years. People have to learn to sort out problems on their own, with our help of course, where we can, but there isn't the money to do everything."

We'll be interrogating the council over how they are going to deliver this 'behavioural change' in the coming weeks. But it's a welcome thought.

And is probably a way to get that voter turnout higher. If people are citizens not consumers then they will want to register their stake in the city by voting.

Leese is right to differentiate between 'the citizen', an active member of city life, a contributor, and 'the consumer', a purchaser of goods and services, one who in effect stands apart.

The Labour Leader of the Labour dominated Manchester City Council wants a return to traditional values. Now which other political party harps on about those?

For Sir Richard Leese it seems, it's: 'Ask not what your city can do for you, ask what you can do for your city.'

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+

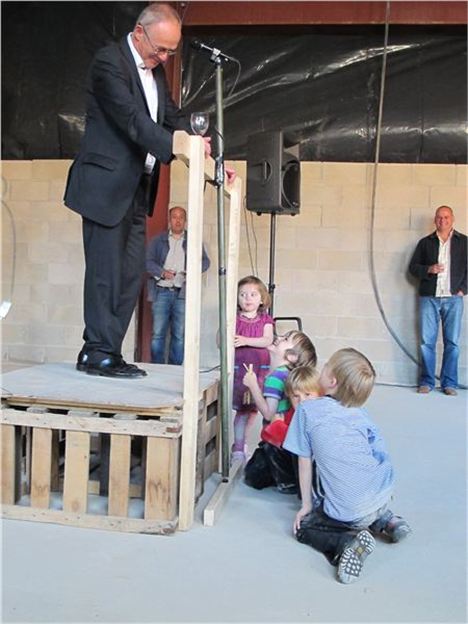

Sir Richard Leese engaging with young constituents at an Ancoats' opening

Sir Richard Leese engaging with young constituents at an Ancoats' opening