MARK Kermode is a charming person.

One of those generational broadcasters who demonstrate sufficient intellect to appeal to the geeks and specialists in their broad audiences yet also have an everyman delivery that feels down to earth, even humble.

I came up to Manchester to university in ’82,” says Kermode. “There was City Life, a cooperative. After asking repeatedly I eventually got a job on ad sales and I was useless.

Recently Confidential’s been collecting these generational gentlemen.

I've interviewed Paul Morley this year and our absurdist, Sleuth, has recently encountered Stuart Maconie, while Mark Radcliffe launched an ale in a MCR pub; a launch we covered.

You could almost see Kermode, Morley, Radcliffe and Maconie living in a big house together and running a TV and radio network called KMRM. They’d bag a whole section of the broadcast audience.

Of course Kermode is the only southerner out of these North Western boys, but he’d have plenty to say about his time in Manchester in the eighties when he first became a film critic.

I meet Kermode ahead of his Bridgewater Hall concert, Film Music Live with the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra conducted by Robert Ziegler. Kermode is well known for his film buffery and cultural commentating on Radio 5 Live, the Culture Show, The Observer and in countless books and programmes.

We sit in the festival of bland that is the downstairs bar area of the Holiday Inn at MediaCityUK. We have a chinwag and a reminisce, serenaded by a soundtrack from the hotel speakers that makes BBC Radio Manchester’s choice of music appear edgy.

Being a film critic

“Is a film critic the best job in the world?” I ask. “Given you have to watch so many movies and take the very rough with the very smooth and the 3d?”

“It’s a lovely job,” says Kermode in that comforting and rapid tone of his. “I watch ten or twelve films a week. Four on Monday, four on Tuesday and then the rest spread over the other days. Monday and Tuesday are the main screening days.”

“Given your status as the darling of film criticism in the UK at present, is there a special Mark Kermode preview screen somewhere?”

“No, no,” says Kermode. “It’s a ritual. The preview theatres are around Soho, on Wardour Street, Dean Street, Soho Square. It’s all in a compact area. You go to there on a Monday at 10am for the first screening and 1pm’s the next one. At 12.30 you could catch every single British film critic trudging from one or another other screening with a glazed look on their faces. We’re like a pack of dogs. But really the job is very simple, it’s watching films for a living and telling people about them.”

“Lots of people do that,” I say. “But not many of them have your notoriety. What do you think’s your secret? Is it the ability to get complex thought across simply?”

“That’s sweet of you to say,” says Kermode, “but it’s other people too. I’ve been lucky enough to be put in rooms with Danny Baker and Simon Mayo, broadcasters who are brilliant and bring out the best in everybody. That’s the key to it.”

A gracious man our Mark Kermode but before I ask another question he continues.

“Another key is getting in a position to do this. That starts with walking into City Life in Manchester in the early eighties and asking to be part of it, and then walking into Time Out in the late eighties, then into Danny Baker’s studio in the early nineties and Simon Mayo’s in the late nineties. Persistence.”

Manchester and City Life

“Tell me a little more about City Life and Manchester. I was at an event with Mike Hill (an ex-editor of City Life) the other day and he remembered you clearly. Good times?" I ask. City Life was Manchester's listing and comment magazine, eventually subsumed in the Guardian Media Group. It still exists online, albeit now part of Trinity Mirror.

“Very good times. City Life when it began in the eighties was a tight group. I remember them all, Mike Barnett, Mike Hill, Andy Spinoza, Ed Glinert, Chris Paul and so many others. It was a co-operative at the time and it all began there for me. Sometimes people ask me how do you become a film critic? The answer is that in the current world, I don’t know how you'd do it.

“Back then you could walk into offices. Now you wouldn’t get past the door. NME used to be off Carnaby Street now it’s in a tower and you need a pass to get in. After City Life I went to Time Out and literally knocked on the door and said, ‘Give me job I’ve written for City Life in Manchester, give me a job please’. And they did.”

“What about those formative Manchester years for you?” I ask.

“I was really lucky because I came up to Manchester to university in ’82,” says Kermode. “There was the student magazine and people there had won a Guardian award and then set up City Life as a cooperative. So after asking repeatedly I eventually got a job on ad sales and I was useless so began writing.

"Of course a magazine was a physical product in those days, nothing digital, we didn’t even have a fax machine. Pages were made with Letraset, scalpel and spray glue. As you were coming up to the issue being sent to print you might have another of the gang, Andy Lovatt, saying, ‘This copy is two inches too long’, and cutting off that bit with the scalpel.”

“All hands on deck then?” I say.

“Absolutely,” says Kermode. “One morning I was picking up the magazines in the City Life van from the printers to bring them back to the office for distribution. I lost control on the motorway. The load shifted in the back or probably I was doing my hair in the mirror. I bounced between the barriers. I totalled the van. It was bad, but no-one else was involved. The van limped back to town.

“I said, "I've had an accident in the van." We got the lovely guy from Manchester Van Hire on the phone. He said very concerned, "Are you all right?” "Yes." "Was anybody else hurt?" "No" "You haven't got whiplash?" "No." The phone went quiet. "You fucking idiot what the hell do you think you were doing!" he screamed down the phone."

He pauses his rush of words for a second, and smiles.

“The whole City Life thing was like a series of stories that we all made up.”

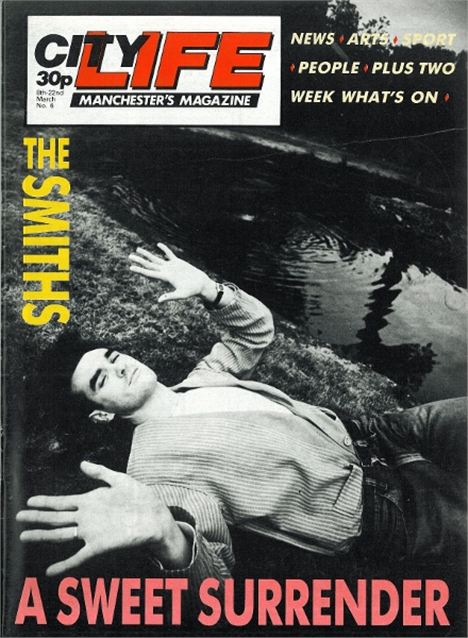

City Life: courtesy of SKV Communications

Film music is personal

One of Kermode's passions is the relationship between film and music.

He's just completing a series of shows with Robert Ziegler and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra presenting a personal choice of film music including Mary Poppins, The Exorcist, Planet of the Apes; North By Northwest, Taxi Driver; The Devils; There Will Be Blood; Twin Peaks and Silent Running.

“The movie music you seem interested in is hardly a rollicking ride through classic popular themes - James Bond, Star Wars and all that - is it?” I say

“No. But I am nothing if not a fan. So I said the music in the shows should be from films that have been important to me as a fan. Not canonical, just my selection.

"Twin Peaks, Fire Walk With Me is an example of that. I loved that film and the music and now more and more people are appreciating it too, but it had been kicked around a lot. One critic from America wrote: ‘In a town like Twin Peaks nothing is what it seems. This isn’t the worst film ever made, it just seems like it is.’ It’s a good line but it killed the film stone dead.

“I once asked the man who wrote the film score, Angelo Badalamenti whether the terrible reviews had hurt him. He said, “It’s one thing for me, another for David Lynch because he’s the director and the film was his child.’ Anyway I’ve introduced the music from Twin Peaks before and it is so good people have said, ‘I love the music, but what’s the film it features in?’ The music can have a separate life from the movie but it can also re-awaken people’s interest in it too. I like underlining that."

We deviate a few minutes talking about silent movies. Kermode says, "Silent movies were never silent of course. They always had music, usually played live in the theatre. Nobody would ever dream of watching a movie silently."

Which is the key of course.

There is always sound. Even if we sit in an empty park on a secluded bench on a windless day and watch the world go by, there are sounds, wisps and scraps of nature, birds, bees, the sound of footsteps as people pass, planes above, the hum of traffic. In the artificial surroundings of the cinema silence except for dramatic effect would be painful.

We return to Kermode's movie music musings.

“Then there’s a lot of my childhood in my choice," says Kermode. "I’ve always had an obsession with Mary Poppins. I love the overture which is a bit of this and a bit of that, a jukebox of popular songs from the musical.

“When I was a kid you saw a film and then it was gone, not like today with DVD sets and Sky Movies. One of the ways you could grab a bit of the movie was through the soundtrack album. You’d sit there playing the album remembering the film, and that was our video or DVD collection. Mary Poppins was important because I played it over and over again.”

Horror and Sci-fi

“There seems a lot of horror and sci-fi themes you like,” I say. “I suppose horror and sci-fi use music more than other movie genres to create mood?” Kermode gained a PHD from the University of Manchester in 1991 writing a thesis on horror fiction.

“That does happen,” says Kermode, “and I am drawn to elements of those types of movies. The Exorcist is a good case in point. The director Friedkin wanted the music to be a ‘cold hand on the back of the neck’. After lots of false starts Friedkin stumbled upon the opening bars of Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield.

“He said, 'That’s it!' Friedkin says he never heard the rest of the album which turns into a guide to the orchestra if you know it, but it was those opening bars which worked. Because it really does become the ‘cold hand on the back of the neck’, it really does establish mood and atmosphere.”

“Why is classical music so emblematic of movie music - with the strings especially?” I ask.

“Well it’s not always the case, and I could give examples,” says Kermode. “But it’s always been a part of it. And there are a number of orchestras that do very well on that basis. I suppose there are certain things that just sound right, there is something about strings for example...maybe they match the scale of the cinema. They seem right. Like the shape of the screen and the way it works seems right. It all comes together.”

Kermode takes a breath and jumps onto one of his bandwagons..

“3d movies I find just don’t feel right, seem a cheap gag. In fact I made a cheap gag once about Avatar on a book tour. I did a live version of the film by putting three smurfs on a coat-hangar and said, ‘If you’ve seen the 3d version, then this is the 2d version of Avatar’. Then I got a twenty foot long pole and stuck the hangar on the end with the smurfs and waved it over the audience’s head and said, ‘And this is what it looks like in 3d.’”

Kermode doesn't want Stardust

Just then, Take That comes over the Holiday Inn’s sound system with Rule the World from the film Stardust.

“Does this song feature in your personal choice, it’s movie music?” I ask.

“Oh God, you’re right this is film music," Kermode says with a shudder, and laughs. "But no, we’re not doing this. Ever."

As we leave Kermode tells me to pass on his warmest regards to his ex-Manchester colleagues on City Life.

He's that kind of man. Thoughtful it seems. Maybe he has a stamp-the-foot attitude when he's not being interviewed. Probably not. The 50-year-old seems a perfectly pubable man. One you could have a relaxed chat with over a drink or two.

Perhaps if he has a dark side it's in his liking for horror movies. Maybe that's where he keeps the skeletons in his cupboard.

And of course, behind the charm there's a touch of ego.

To base an entire series of concerts around your own occasionally mysterious personal choices, morphing your role as critic into the arbiter rather then the commentator, might appear a little self-centred.

As perhaps does his 'style': quiff, heavy glasses, dark suits and ties. Then again, as revealed above with his desire to succeed as a film critic, his 'persistence', he knows what he's doing. His 'look' has become a brand to match his vocal delivery and his dislike of 3d.

The latter might be his Achilles' heel.

As he enters his fifties that hatred of 3d might cast him as a fogey before his time. Technological leaps are part of the very essence of movieland's brief history. Maybe Kermode should embrace a whole different pair of spectacles, learn to love 3d, reinforce that easy everyman character.

Mark Kermode: Film Music Live has been touring the country. More details here.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+