Jonathan Schofield on how CP Scott’s words are being ignored, to all our cost

FACEBOOK got a good kicking from British MPs last week.

“Democracy is at risk from the malicious and relentless targeting of citizens with disinformation and personalised ‘dark adverts’ from unidentifiable sources, delivered through the major social media platforms we use every day,” warned the committee’s chairman, Damian Collins, summing up a report in which the digital giant was condemned for behaving like a ‘digital gangster’.

Collins also said: “Mark Zuckerberg continually fails to show the levels of leadership and personal responsibility that should be expected from someone who sits at the top of one of the world’s biggest companies.”

Zuckerberg, and the rest, in the subjective world of social media, might do well to take a 98-year step back, to Manchester in 1921.

While Zuckerberg’s manipulative company is clearly a problem (with its alerts telling people, in effect, they are somehow weird, lonely, mad and bad for not having interacted with their ‘friends’ for a week or a month), it reflects the mood of the times.

This, in part, is dictated by the Bedlam Hospital that is the internet, where almost everybody in the asylum gets to scream what they want when they want, unedited and unmoderated. Thus, subjectivity rather than objectivity rules. This shift in how many view the world covers just about every issue including certain aspects of identity and gender politics, 'no-platform’ student unions, gillet jaunes protesters and even aspects of our own judicial system and policing. It’s enough to feel yourself disadvantaged, rather than have to prove it, to have your voice heard by ‘friends’ and sometimes the authorities.

Of course, to an extent this has always been the case, especially with whipped-up crowds and mobs. The only difference is the mob is not contained in a public square anymore, but let free across the world wide web. Facebook and other social media are simply the most efficient weasel platforms defeating objectivity. Thus, people form agreement groupings and ignore other voices. They feel warm wrapped up in their own monomanias with their mates providing the comfort blankets, and the last thing they want is an expert showing evidence to the contrary.

This is discussed in a fine New Statesman article, ‘How can we teach objectivity in a post-truth era?’ by Simon Blackburn.

He writes: ‘A person can (be) too ready to believe whatever comes across on Twitter or Facebook, and too dismissive of a consensus achieved by careful, patient, skilled investigation by trained scientists, historians or even scrupulous journalists….(So) people believe what they want to believe…and refuse to believe what they don’t want to believe, however well attested it is.”

He goes on to say: ‘Once caught up in a cascade or chain reaction, people refuse to listen to evidence. In science, history, law, economics, or politics, the only way to recover from particular wrong turns is to go over the ground again, more carefully. Yet those who are already taken in by one particular version of the truth are unlikely to pay attention to this.

‘Yet when somebody decries the very idea of objective inquiry, it is good to ask whether, if they were falsely accused of possessing and using counterfeit currency, they would prefer the investigation to be careful, patient, open-minded and thorough, or the reverse of all these things.’

Zuckerberg, and the rest, in the subjective world of social media, might do well to take a 98-year step back, to Manchester in 1921.

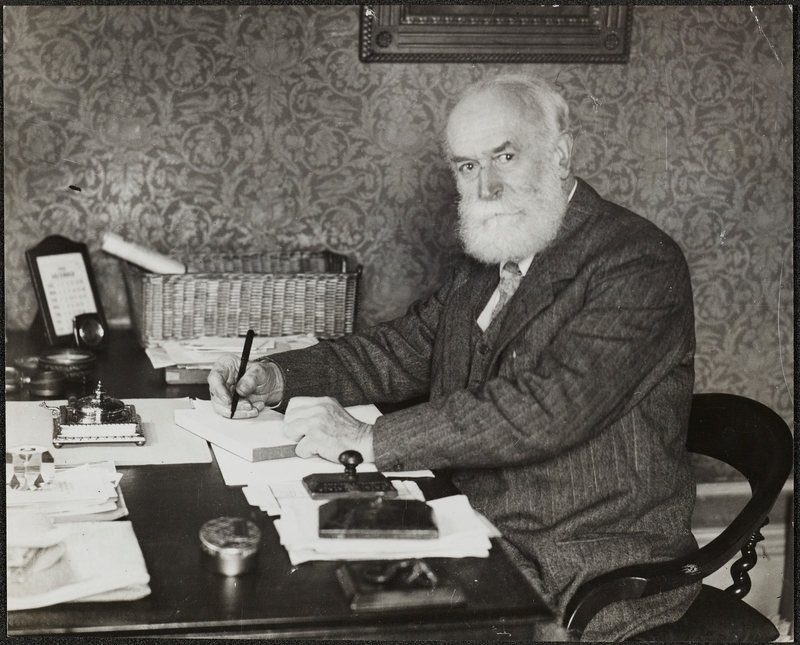

The best definition of what all media, let alone social media, might at its best, attempt in terms of objectivity, comes from CP Scott, 57 years the editor of The Manchester Guardian, now The Guardian.

He wrote what could almost be described as a beautiful prose poem to journalistic integrity on the occasion of the centenary of the paper. This contains his most famous line, ‘Comment is free, but facts are sacred’. Good stuff, yet read the quote with the rest of the passage and that line achieves greater potency.

'I think I may honestly say,’ wrote Scott, ‘that, from the day of its foundation, there has not been much doubt as to which way the balance tipped as far as regards the conduct of the paper whose fine tradition I inherited and which I have had the honour to serve through all my working life. Had it not been so, personally, I could not have served it.

‘Character is a subtle affair, and has many shades and sides to it. It is not a thing to be much talked about, but rather to be felt. It is the slow deposit of past actions and ideals…and so it is for that latest growth of time, the newspaper.

‘Fundamentally it implies honesty, courage, fairness, a sense of duty to the reader and the community. A newspaper is of necessity something of a monopoly, and its first duty is to shun the temptations of monopoly. Its primary office is the gathering of news. At the peril of its soul it must see that the supply is not tainted. Neither in what it gives, nor in what it does not give, nor in the mode of presentation must the unclouded face of truth suffer wrong.

‘Comment is free, but facts are sacred. "Propaganda", so called, by this means is hateful. The voice of opponents no less than that of friends has a right to be heard. Comment also is justly subject to a self-imposed restraint. It is well to be frank; it is even better to be fair. This is an ideal. Achievement in such matters is hardly given to man. We can but try, ask pardon for shortcomings and there leave the matter.’

Of course, Facebook and Twitter are not newspapers, but the fundamental idea in the magnificent line, ‘It is well to be frank; it is even better to be fair’, might inform their passive notions of regulation.

More pertinently, the tail is now wagging the dog.

The methods used by Facebook and others inform the behaviour of our traditional news-gatherers. Read a Daily Telegraph thirty years back and the level of Conservative reasonableness and ‘fair’ reporting is plain to see, even The Daily Mail was more measured. The Guardian was still, more or less, applying Scott’s principles too. That’s been blown away in 2019. Scott recognises his paper in 1921 is about leftish, reformist principles but understands he must avoid hateful 'propaganda'.

The opinion articles of both The Telegraph and The Guardian (as two examples of opposed but 'serious' papers from 2019) have taken the words, ‘The voice of opponents no less than that of friends has a right to be heard’, and largely trashed them. The stridency of Christopher Booker on one side, and the whining of Owen Jones on the other, prove the web’s coronation of the subjective is sovereign.

If this is the internet’s liberation of thought, it’s terrifying. At least, objectively.

Follow @JonathSchofield on Twitter.