SLAY him, smite him, that pagan beast. Ride him down lad, apply the lance (if it's not been nicked)

St George saving the maid from the dragon was the personification of the determination of the English race, the embodiment of its selflessness, the measure of its courage, the essense of its honour, the clarity of its vision

April 23 is St George's Day and Manchester has its fair share of St Georges on buildings and memorials in the city centre.

'Cry God for Harry, England, and Saint George!' shout the English soldiers before battle in Shakespeare's Henry V. The English army then take on the much larger French force at Agincourt and win. Of course.The statues and sculptures mainly date from the days when the patron saint evoked the heart of English oak at the centre of the world's greatest empire.

Shakespeare's poetic licence became an inspiration for our forbears a century or so ago.

St George saving the maid from the dragon was the personification of the determination of the English race, the embodiment of its selflessness, the measure of its courage, the essense of its honour, the clarity of its vision.

St George is us these works say. And we are him.

In some ways perhaps we'd expect more Georges.

But up to World War II for people who were keen on this type of symbolism the concept of Britain was more potent than that of England (even when they said England they meant Britain). There are more Britannias than Georges in Manchester.

Personally I'm pleased.

I much prefer the concept of Great Britain rather than Little England - damn that 2014 Scots referendum. Diminishes us all.

Anyway here are the St Georges of the city centre.

Choose your favourite.

Mine is probably the vigorous scrapper on the top of Queen Victoria's otherwise remarkably ugly Piccadilly Victoria memorial.

St George by Henry Shelmerdine and the Studio of George Wragge. 1922. Victoria Station War Memorial

Calm St GeorgeHe may have had his lance nicked sometime over the years but this is a powerful work, on the moving war memorial in Victoria Station.

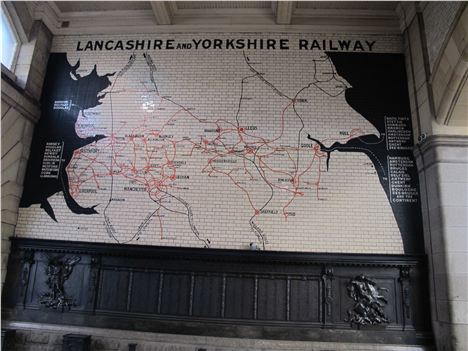

The memorial in bronze carries the names of the WWI war dead of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company, some 1,465. There's a spectacularly scary St Michael breaking the back of the devil on one side of the work and our St George on the other.

It's a powerful piece that could adorn the 1,899 year old Trajan's Column in Rome. There's also something wildly pagan about the design with the strangely small dragon (they're often depicted this size, perhaps so they could fit easily within the frame of the artist's work) cowering underneath the rearing horse of the saint.

Trajan's Column detailThe face of St George is weirdly benign in Shelmerdine's design despite the violence of the scene. But then the saint is an otherworldly presence of course, and his destination is direct to heaven.

Trajan's Column detailThe face of St George is weirdly benign in Shelmerdine's design despite the violence of the scene. But then the saint is an otherworldly presence of course, and his destination is direct to heaven.

The symbolism of the work is simple, the Brits and their allies, have triumphed over the evil Germany Empire - the dragon is seen in some of the earliest representations of St George as the embodiment of the pagan Roman Empire. To substitute one for the other was simple enough.

The saint also represents the return of order to Europe after four years of war and sacrifice - shame the peace only lasted twenty years.

St George in Victoria - so to speak

St George in Victoria - so to speak

St George, St Michael and the routes of the former Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company

St George, St Michael and the routes of the former Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company

St George by Onslow Ford. 1901. Detail from Queen Victoria Statue, Piccadilly Gardens

'At once the most pretentious, the most incoherent and most inept of any sculptural monument one has ever seen in England,' wrote the Westminster review of Manchester's Queen Victoria statue.

It's hard not to agree given the depiction of the late monarch as a big bronze beetle melting all over the farcical Baroque marble surround.

But there's charm in the grotesqueness too. On top of the monument, missed by all and sundry, is a cracking and cute fighting St George and his horse all twisted up in the serpent at his feet, but getting in that killer strike.

This St George has a cartoon-verve about him, a comic book swagger of heroic energy. Super-Saint George, fighting the good fight for the miserable monarch beneath.

'Most inept of any sculptural monument one has ever seen in England'

'Most inept of any sculptural monument one has ever seen in England'

St George by unknown artist, copy from Donatello, 1911, St George's House (former YMCA)

The artist who cast St George over the entrance to what was the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) in Manchester, did a fine job.

The piece is a direct copy of the sculpture by celebrated Italian Renaissance artist, Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (circa 1386 – December 13, 1466), better known as Donatello. That sculpture was commissioned by the Armorer's and Sword Makers Guild and completed around 1417-18. It still survives on the north side a church on Via Orsamichele in Florence.

A near contemporary description is best from Francesco Bocchi. 'The legs move, the arms are ready, the head alert, and the whole figure acts; by virtue of the character, the manner and form of the action presents to our eyes a valiant, invincible, and magnanimous soul.'

The cast captures the pensive but determined look on St George's face as he is about to do battle with the dragon. It's stockier and not as finely moulded as the original but that's fitting, you wouldn't want the copyist outdoing the master.

Manchester's terracotta St George was surely meant by the YMCA as an embodiment of all the masculine virtues people visiting its Manchester arm should look for in themselves. Here is the thoughtful hero, courageous but not insensible, physically strong (the YMCA building here included a gym, pool and running track and the healthy bodies - and clean minds) yet compassionate and gentle, a shield, and he carries his here, against wild passions and recklessness.

Donatello's original in Florence

Donatello's original in Florence

St George by Farmer and Brindley, 1873, Manchester Town Hall

Now we leave the fighters and get to the pensive heroes just prior to fight with the dragon or just after it.

In Manchester Town Hall's case, the noble St George with his famous shield crowns the entrance decoration high above the main doorway, on a gable bearing Manchester's coat of arms.

As with the better work described above this is perhaps a representation of Donatello's St George - the pose is similar. It's often thought that the latter statue originally had a helmet, in which case the well-known Victorian pair of architectural sculptors, Farmer and Brindley, have re-supplied the helmet.

Can you spot St G?Alfred Waterhouse who designed Manchester Town Hall always conceived of it as a unified application of all the arts with architecture. He has mosaics and metalwork on the interior and the painter's art too, with the Manchester murals by Ford Madox Brown in the Great Hall.

Can you spot St G?Alfred Waterhouse who designed Manchester Town Hall always conceived of it as a unified application of all the arts with architecture. He has mosaics and metalwork on the interior and the painter's art too, with the Manchester murals by Ford Madox Brown in the Great Hall.

The artwork could be used to give Manchester an extended history lesson. Hence the historical figures associated with the city such as General Agricola who is said to have founded a fort and thus began Manchester's history - his sculpture is directly below St George's.

The patron saint is purely symbolic of course, not historical.

He represents Manchester's place in the country at large, but surely also the bastion of order and good management that a well-run civic administration represents.

Here the dragon-slayer is a watchman, a councillor, a ward against corruption and selfish patronage, looking out across the city, protecting and encouraging its citizens.

St George as the good councillor

St George as the good councillor

St George by Eric Gill, 1933, Manchester Cathedral

The hardest to find external St George in the city centre is the one over an entrance into an annex of Manchester Cathedral.

The sculptural relief shows the three saints that give Manchester Cathedral its full name: The Cathedral and Collegiate Church of St Mary, St Denys and St George in Manchester.

St George is crouched down on the left of this work with his lance and his squashed serpent, looking up to the Christ-child in the Virgin's arms.

This is the most directly Christian evocation of the English patron saint in the city centre. There is no representation of the red cross on white, just a suppliant and worshipping figure, a gentle knight, although the presence of the lance indicates his capacity to act as a soldier of God.

The sculpture is sweet rather than dramatic, low-key, if one considers the contemporary work of Eric Gill, such as the powerful figure outside the BBC's Broadcasting House in London, or the wondrous designs in the Midland Hotel, Morecambe.

Gill has gained modern notoriety through Fiona McCarthy's biography which detailed his brilliance but also his incest and bestiality. He was never in control of his passions like the idealised St George.

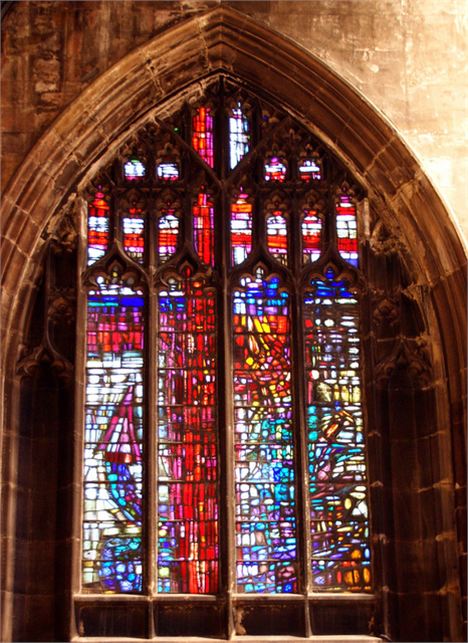

The Cathedral has a several interior representations of St George including a spectacular post WWII window from Tony Hollaway and the charming but damaged wooden carving of the saint, again stood on his defeated dragon, from the mid-1400s. That is the earliest representation of the saint in Manchester, way before the current mania for waving little plastic flags in red and white.

Gill's spectacular work at The Midland in Morecambe

Gill's spectacular work at The Midland in Morecambe

Tony Hollaway's St George's window

Tony Hollaway's St George's window

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+