DR JEFF Forshaw is one of those blokes that makes you feel a blithering idiot.

But what if it’s all just random? What if our universe is just one of a large number of universes each with completely different laws of physics like some power playing dice. What if we’ve just happily landed in this one

Not that he means to, he’s a lovely bloke, chatty, responsive and unassuming. He has the ability to boil down hugely complex theories and present them to us serfs in a nice little science biscuit.

It’s just that he is so achingly intelligent that you come to realise you possess the cognitive ability of a toad. A thick one. The one that flunked toad exams.

Dr Forshaw is Professor of Particle Physics at The University of Manchester. Having achieved a First from Oxford and a PhD in Theoretical Physics at Manchester, Forshaw has produced over 100 academic papers, appeared on The One Show and BBC Breakfast, penned a number of books with titles you won’t understand and written two more popular science books for the layman with best-mate Brian ‘Sexy Science’ Cox.

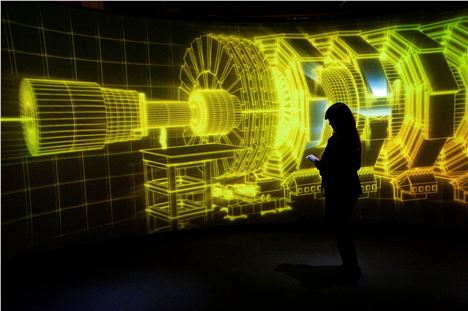

Confidential met with Forshaw at the University to discuss the upcoming Collider exhibition (running from 23 May-28 Sept 2014) at the Museum of Science and Industry.

Collider: Step Inside the World's Greatest Experiment is bringing CERN (The European Council for Nuclear Research) and the Large Hadron Collider to Manchester. Not physically. 27km of particle speedway buried nearly 200 metres beneath the Franco-Swiss alps is not easy to dig up, but Collider is taking a good bash at recreating the experience.

This behind-the-scenes look will ‘transport visitors into the heart of one of the greatest scientific experiments of our time’, blending theatre, video and artistic sound. During its stint in London, the exhibition attracted more than 25,000 people in its first two months.

Forshaw has spent time working at CERN, that’s when he’s not in Manchester studying the phenomenology of elementary particle physics. Today I’ve mostly been studying the phenomenology of a sausage roll. Toad.

WARNING: Before entering there's a 'Higgs boson for dummies' right here.

Here's a selection of Forshaw's science biscuits to nibble at.

Forshaw on bringing CERN to the people.

“Yes. If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be a scientist at CERN, what it feels like to be part of a monumental discovery, then this exhibition is the closest you’ll come. Straight away you’re transported into the audience when the discovery of the particle, that missing piece in the jigsaw, is announced. You see the scientists beavering away trying to understand the origins of the Universe."

On why everything isn’t whizzing round at the speed of light.

“People get carried away and call the Higgs the 'God particle' because without it, everything would just dissolve and start whizzing around at the speed of light. The laws we were trying to understand didn't work, because the particles looked to have no mass. The Higgs particle explains the origin of mass in the Universe, so why everything isn’t whizzing about and why atoms are allowed to form. But we’d never seen this particle, Peter Higgs predicted it was there in the 60s. CERN was built to find it.”

On imagining a needle in a haystack, it’s much, much worse…

“The detection is the difficult thing. At CERN they’re smacking protons into each other around a 27km ring at a fearsome collision rate of about a billion every second. Yet they’ve only managed to harvest a few thousand of these particles. It’s the needle in a haystack, but immeasurably more difficult. There was no guarantee we’d even find the Higgs. It really was a journey into the unknown. But then, there’d be no point building it if we knew what we were going to get."

On finding the stuff of the universe.

“The theory is crucial to understanding what happened at the birth of the universe, it tackles directly the questions of our origins. The ultimate goal is to find out what the ‘stuff’ of the universe is, how it behaves. To state we’re trying to understand the origins of everything does sound very grand, but it draws people in, it has real profundity. Scientists, we’re like the archaeologist that sees a ruin coming out of the dust, things become clear but there’s much more to know beneath the surface."

On the relationship to Manchester.

“The starting point for all particle physics was in Manchester when Ernest Rutherford split the atom in 1911. There’s still a large involvement with Manchester University, we’ve got about a hundred people at the end of Brunswick Street working on data from CERN as we speak. Most of them will spend significant time at CERN, their experience is mirrored by this new exhibition. They’ve got mock-ups of the corridors and offices. Anybody that wants a taste of working there needs to go.

On the Collider being an old, fat TV.

It works in a similar fashion to one of those big, old, fat televisions. They had a big back because they were essentially boiling off electrons from a piece of metal at the back - that’s why you’d see them glow - then accelerating them to hit the screen in different parts using an electric field and magnets. At the collider the particles are accelerated from A to B using an electric field then bent using magnets to travel around the 27km ring. It's a very similar principle.

On Higgs being a cow.

Now we think we’ve found it, we have to measure its properties. It’s like seeing a cow in a field from a distance, you want to to go up and check it has four legs, udders and moos. Peter Higgs didn’t just say there’s a particle in there somewhere, so go find it. He said it should also possess these properties and behave in this way. We’re checking that it behaves itself.

On dark matter, what’s its problem?

“Next up is dark matter, so called because it doesn’t shine. When we look into the universe we only see things that emit light. If it doesn’t emit light we can’t see it. The universe hasn’t made it easy for us. We know there’s a load of this dark matter out there because it bends light from distant galaxies on its way to us. We have charts of the stuff, we have evidence it's there, but we don't actually know what it is. Higgs must be a smaller part of a bigger jigsaw containing dark matter. At CERN we're trying to make it visible. That’s top of the list.”

On why science unites the world.

“CERN is very similar to a University. It’s a place of learning shared by all nationalities, all ethnicities. It’s inspiring to see a significant portion of the world’s countries, us, China, the US, Russia, Israel, even Iran, all working towards a shared goal. It’s a fantastically unifying thing science. It unifies in a way politics never could. Everybody wants to understand where we came from.”

On why every time you open your mouth it's bullshit.

“There was a debate about whether scientists should govern the world recently. I don’t think we’d be much better than anyone else, politics is a different animal. But we scientists do understand how easy it is to be wrong. I tell my PhD students that everytime they open their mouths, they should assume it’s bullshit, because then you have to work tirelessly to convince people you’re right. You hear politicians speak with such certainty about something that’s probably nonsense.”

On what happens if it’s all just ruddy random?

“There’ll always be unanswerable questions. Trying to understand how we came to exist, it touches on theological, philosophical, metaphysical questions. But what if it’s all just random? What if our universe is just one of a large number of universes each with completely different laws of physics like some power playing dice. What if we’ve just happily landed in this one in which we can exist, but others are failing because their laws of physics don’t lend themselves to life. That has sever theological implications. It can’t be the result of an omnipotent being, because everything is random.”

On CERN creating the internet, and that not being the plan.

“When you ask what the point is, some things don’t have an immediate point. Medicine, for example, has an immediate point. Others have uses we can’t yet anticipate. The answer is not necessarily the reward, it’s getting there. Where we are now has been one long human toil to understand. Some results you can’t predict, the world wide web was invented at CERN by Tim Burners-Lee. We could never have predicted how it would change the world.”

On an infinite universe... where's the edge?

“There’s no indication to date that the universe isn’t infinitely big. But don’t get hung up on it, it’s inconceivably big. Currently we can see out to 13.8 billion light years away, but every day we see further as more light reaches us from further away. So we know there has to be something beyond. Everyday it gets bigger. People look for an edge, but there isn’t one. There’s not one shred of evidence to suggest the universe isn’t and hasn’t always been infinitely big. That all came from one tiny little atom. But that was a drop in an ocean of these atoms. We’re inclined to think that our universe is the only one, that’s very likely untrue.”

On dark energy.

“If I could understand one thing right now it’d be dark energy. We know even less about dark energy than dark matter. It looks like it’s smooth across the universe and responsible for accelerating the universe, making the Big Bang faster. But that doesn’t make much sense. The best understanding we have leads us to conclude that the universe, accelerated by this dark energy, should have quickly expanded to the point where no life could form. We’re very confused about that one.”

On why scientists aren’t robots but artists too.

I don’t subscribe to the two cultures idea of art and science. This pursuit of contextualising our place in the universe has huge cultural value. Great art has often stemmed from the very question we seek to answer, where we came from. The process we scientists go about is entirely creative. Being a scientist is akin to being an artist, we use guess work too, follow our feelings and instincts. That’s something that isn’t often recognised, we’re seen as robots.

On why the universe is a beauty.

Peter Higgs said that the equations were too beautiful to be incorrect. An equation is art, but when you say equation the blinkers come down. But give someone a quarter of a snowflake and ask them to complete the rest through symmetry. It's the same with an equation. You’re inextricably drawn to complete the picture, it’s like you have no choice. Nature is telling you what to write down and what the world should look like. It’s like Michelangelo knocking David out of the stone and saying ‘he was already there’.

Peter Higgs and Stephen Hawking

Peter Higgs and Stephen Hawking

Collider: Step Inside the World's Greatest Experiment will run daily between 23 May and 28 September 2014 from 10am to 5pm.

Tickets are priced at £7 for adults and £5 for concessions. Entry is FREE for under 7s. Tickets here.

Museum of Science and Industry, Liverpool Road, Castlefield, M3 4FP.

0161 832 2244