THIS is a tour-de-force of fancy.

The Market Street scheme provides us with an insight into the Victorian obsession of using history as a guide to what should be built in the present

It seems the amount of traffic using Market Street was becoming a concern to Manchester Corporation in 1895, so its Market Street Area Committee had an idea. It proposed a boomerang-shaped street from Exchange Station, close to the Cathedral, directly to Oldham Street with the ultimate goal of reaching London Road Station (now Piccadilly Station). This would have run parallel to Market Street.

This is how a contemporary account in Manchester Places describes the idea:

‘The new thoroughfare, it is thought, would relieve Market Street of some of this pressure of traffic, would be a desirable addition to the city and would form an almost direct and continuous way from London Road to Exchange Station.

‘It is, almost needless to say, that the scheme from that point of view is not regarded with particular favour by the majority of the traders in Market Street. They have a preference for an entirely busy highway and do not desire “relief” of the kind suggested. The new street the committee propose should be 60 feet wide. The corporation acting as the holder of the land contiguous to it, although they would not themselves build property, would have the power of determining the class and character of the buildings to be put up on either side of the street.

‘The suggestion is that Manchester should have a thoroughfare not unlike those which form the old Rows at Chester with intersecting bridges for the convenience of foot passengers.’

If you want to understand how bad Market Street congestion was then take a look at this image from a few years later in 1914.

Market Street and Cross Street junction in 1914, congested but mightily busy

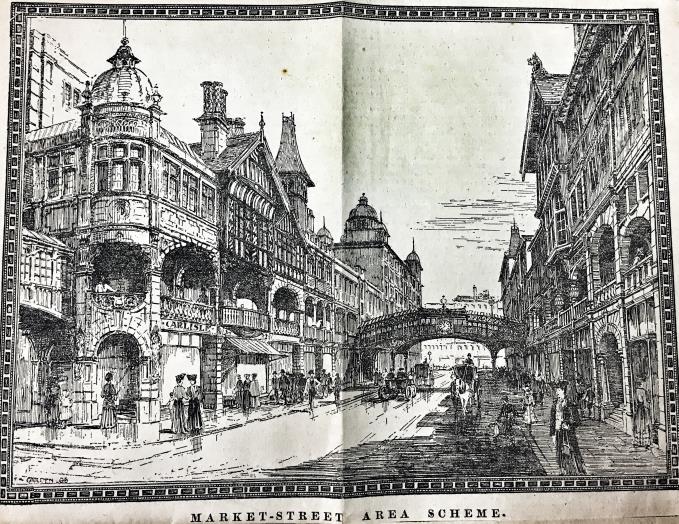

Market Street and Cross Street junction in 1914, congested but mightily busyStill the image shown at the top and bottom of this page is beguiling. The style of the buildings and the manner in which it is drawn suggests John Douglas, the half-timber specialist, may have had a hand in it or at least helped inspire the proposal. Douglas did much of the work in Chester we might think of as medieval and much of the work in Worsley we guess isn’t. The sketch appears to be signed by one FW Grouden or Goulden. History is fickle and this forgotten man is lent an afterlife here: let's hope his spirit is tickled by this unlikely turn of events.

'The Rows' would have stretched from Exchange Square to Piccadilly Station

'The Rows' would have stretched from Exchange Square to Piccadilly StationWhat is especially interesting in this plan is the separation of people from vehicles. There is a charming bridge over the road straight ahead and another elegant structure to the left of the sketch. People move on roadside pavements but also at first-floor level and over the bridges. In effect people need not reach ground level in this new system. In effect we’ve got streets in the sky.

This is a High Victorian anticipation of Hulme and Fort Ardwick in Manchester and all the nationwide deck-access failures of the 1960s. Of course, rather than cold concrete the Victorians would have used brick, stone, timber and stained glass in the new street. The scheme would also have run through the site of Manchester Arndale, anticipating the split-level shopping in the present mall but providing more charm and a lot more intricate detail.

Of course it never happened, nor did a reduced plan on the same lines, but the Market Street scheme provides us with an insight into the Victorian obsession of using history as a guide to what should be built in the present.

This scheme is one of many appearing in Jonathan Schofield's new book Illusion and Change in Manchester, due to be published in late July by Manchester Books Limited.