“I WANTED to be like a buffalo,” says Kim. “I was so full of anger and hate for so many years. I wanted all my scars, my burnt skin, covered with hair like a buffalo's so no-one could see it. I still have pain but I hide the scars. Look and you will see why I felt like I did.”

I knew immediately it was important

Phan Thi Kim Phúc, known simply as Kim, rolls her sleeve and I look at a forearm rippled like tidal sand on a shore.

“Feel it,” she says.

I run my fingers along the ridges of flesh. I try to imagine napalm burning down my back and arms, the skin on fire. I get nowhere, the scale of the pain off any register I can muster.

Kim’s life was defined by two moments on Thursday 8 June 1972.

During the Vietnam War her village Trang Bang had been occupied by North Vietnamese forces. It was then attacked by the South Vietnamese assisted by the Americans. As Kim fled, a South Vietnamese pilot seeing the running civilians presumed they were enemy soldiers and hit them with napalm.

That was the first moment.

As Kim tore off her clothes shouting “Nóng quá, nóng quá” – “Too hot, too hot” she was about to become a death statistic amongst millions that died in two decades of war (estimates vary wildly from 1.6m-3.8m total dead in the Vietnam War).

Then a double click, a shutter moves, and captures a 9-year-old child in pain, arms spread like a crucifixion, naked, running from a man made hell. It captures innocence, savagery and injustice. It wrings the heart.

That was the second moment.

Nick Ut, a 20-year-old war photographer at the time, pressed his finger and one of the defining war images was made real.

"I knew immediately it was important. In the war I took pictures of people and the effects of war on people. I wanted to be close to humanity and how it suffered."

'The effects of war' had made him an Associated Press photographer in the first place.

"My older brother was in the war as a photographer, he was shot in the Mekong Delta, so I carried on for him," says Ut. "I was sixteen when I became a professional. So young, but I was determined to get close to what was happening to show it as it really was."

"Sometimes it seemed I was so close people wouldn't believe the pictures I took," he continues. "President Nixon when he saw the picture of Kim and the napalm attack thought it had been an anti-war campaigner's 'fix'. That was what he called it, a 'fix'."

Others knew the impact it had when it was published in the New York Times.

"I have met so many soldiers who were serving in Vietnam at the time," says UT, "who thank me for the picture, saying it hastened the end of American involvement. In effect it helped stop the war."

Ut, now 64, compares the war photographer's proximity to the hard point of war with photographers in the 21st century.

"The war was horrible you know. But I talk to photographers who have been to Iraq and Afghanistan and they were so controlled out there. The Americans learnt the lesson of these photographs from Vietnam and we no longer have the freedom to get so close to where the action is except under highly regulated conditions. They don't want an image becoming so powerful."

In an age where everybody has a phone with a camera, where there's Instagram and Twitter, its doubtful whether a single image such as that of Kim's could have the same impact - indeed the most telling images often come from the mobiles of soldiers unmediated by a professional press and thus hidden by the internet rather than exposed. This doesn't lessen the impact of the picture Nick Ut caught. Ut himself was wounded three times during the war in an arm, a leg and the stomach revealing just how 'embedded' he was to his subject. Look through his portfolio and you'll see how he's up there with the bravest and the best of war photographers.

Immediately after the picture of the napalm attack Ut and other photographers helped Kim make it to a field hospital. It looked like the injuries might prove too severe for her to survive but slowly she pulled through.

Kim created the third and fourth moments in her history herself. She founded and is the figurehead for a foundation committed to providing assistance for children psychologically and physically damaged by war. She lives in Canada having asked for diplomatic asylum there with her husband, Bui Huy Toan, after they absconded from a flight between Cuba and the former Soviet Union in 1992. Before then she'd been a propaganda tool for the Vietnamese government.

"I used to be certain no boy would love me but I found love, I had children too and more love came to me and I also found faith, Christianity," says Kim. "I never thought I could be normal, but I can live a normal life. At the same time I know I am, you might say, a celebrity, but I am also down on the Earth, real. Now I use the fame the photograph gave me, that moment in time, to give something back. I believe God had a plan for me. I was in the wrong place at the wrong time and now I'm in the right place."

She pauses. A secular man, I feel uncomfortable with religion and its dogmas. But Kim appears the antidote to dogma.

"I now travel across the world sharing my experience trying to help children in similar circumstances. I am in Manchester today, who'd have thought I'd be here before June 1972 took over?"

She pauses again.

"I was running then, now I am flying," she says with a peaceful, beatific, unnerving expression.

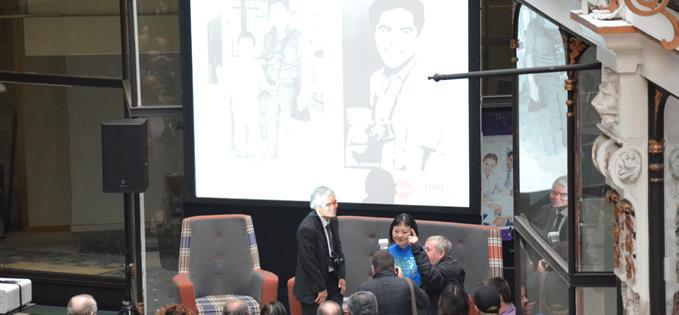

As she takes her place with Nick Ut I feel slightly dazed. This was a girl who became famous under circumstances that sum up the desolation and emptiness of war, that strikes a chord with anyone with an ounce of compassion. Here's a man who proved time and again the cliché that a picture can paint a thousand words. As the event continued I thought how strange it was, in modern terms of reference, to see both the Leonardo and the Mona Lisa of this image on stage, the artist and the subject given equal reverence, both wearing their fame with an easy grace.

Nick Ut and Kim Phúc were hosted in the Barton Arcade with the assistance of Pot Kettle Black at the invitation of the Leica Store in St Ann's Arcade. Nick Ut took the famous image with a Leica camera - "They're the best. The contrast, the focus, superb."