SOMEHOW it was appropriate that when the BBC contacted me for a short tribute to Alf Morris, following his recent death, I was using aids provided under the disabled person’s laws pioneered by him as I was recovering from recent hip surgery.

Like millions of other people in this country I was benefiting from Alf’s life work to improve the lot of disabled people.

Alf’s 1970 Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act was the start of a barrage of legislation he initiated first as a back bencher and then as the world’s first minister for the disabled.

Disabled people received rights and resources via five major Acts of Parliament which dramatically improved their welfare and social landscape, or as he put it ‘this reduced the socially handicapping effects of disability’.

He didn’t just restrict himself to changing laws in the chamber of the House of Commons but campaigned successfully on behalf of veterans suffering from Gulf War Syndrome and haemophiliacs who had been given HIV or Hepatitis C from contaminated blood during transfusions.

He is a loss to politics and his example should be used to make sure he is not the last of his kind.

If the motivation and objective of being in politics is to make a difference then Alf succeeded spectacularly. This country, and indeed the world, is a better place because of Alf’s work. Most MPs would like to make a similar claim; very few have ever been able to.

But the question occurs to me could any politician setting out to make a difference now follow anything like the trajectory Alf followed?

Or to put it another way could an MP born in 1988 sixty years after Alf’s birth make such dramatic improvements in the social conditions of so many people?

This is a question worth exploring because it throws light on how our democracy functions in 2012 compared to the 1970s. Is our democracy better or worse or just different?

It would be a fitting memorial to Alf to use his life so well lived to understand how our democracy can again be used to transform disadvantaged peoples’ lives.

Alf’s politics were formed in the harsh, Dickensian poverty of Ancoats in the years immediately after the First World War. One of eight children his father was severely disabled having been gassed and wounded during the First World War; he died when Alf was seven.

This was a time before child benefit and it took a fight by his local MP to get his mother, a sufferer of severe arthritis, a war widows pension. It is difficult from the perspective of a mature welfare state to imagine how tough life must have been.

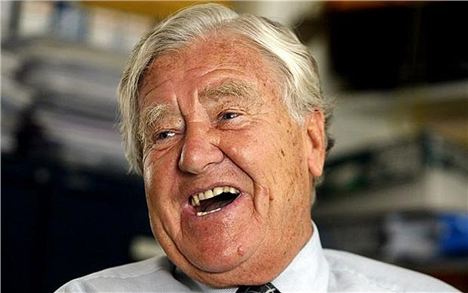

Alf Morris campaigning in Wythenshawe in 1966

Alf Morris campaigning in Wythenshawe in 1966

No prospective Parliamentarian brought up in this country in the last 40 years could have experienced such disadvantage in a loving family. The only contemporary comparable situation might be a child brought up in a dysfunctional, chaotic, drug abusing environment but the deprivations there are of a different kind. So fortunately the conditions that created the steel and determination in Alf no longer exist, but they did create a radical.

It is often forgotten that when he started his political career as the Chairman of the Labour League of Youth Alf was on the left of the party. He was on politically intimate terms with many of the leading Trotskyites of the time and often over a glass of beer would tell less than flattering stories about them.

People of course can be radicalised by more than just social disadvantage, think Tony Benn, but the result is often intellectual not practical. Alf then knowing that he wanted to use his own experiences to help disadvantaged people had first to be lucky. He was.

He came first in the ballot amongst back benchers to put forward a Private Members Bill and he chose the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Bill. This had huge costs associated with it and Harold Wilson the then Prime Minister was strongly opposed.

The difference between then and now was that pressure within the Labour movement and the Labour Party as well as from disabled peoples groups meant that the government relented. There is no example in recent times of a government letting through a Private Members Bill of such magnitude.

Paradoxically the Labour Party of the 60s and 70s had more diverse and independently minded views than the party of today. The rows were often nastier but the compromises more explicit. The Labour Party of today is much more democratically centralist. If the leadership is caused problems its instinct is to freeze out the dissident not compromise.

The answer then to the question could a new MP achieve as much as Alf is a rather depressing no.

The structure of all the parties is designed more for politicians' careers rather than transforming society. First be an MP’s assistant, then a ministerial advisor, then an MP and finally a minister without being touched by direct experience of the outside world.

This is the path of our three main party leaders.

Alf came from a different time fierce on behalf of his constituents (it is often forgotten the tough and effective campaign he ran to develop and protect Manchester Airport, the largest employer in his constituency, from the attacks of Thatcher) and the disadvantaged.

Independent of mind: anti Europe, anti abortion, anti Sunday trading impossible to categorise.

He is a loss to politics and his example should be used to make sure he is not the last of his kind.