LAST Thursday rock and roll hall of famer David Byrne shuffled on stage at the Royal Northern College of Music in a more sedate fashion than his infamous Stop Making Sense days.

Byrne was there to talk about a broad range of topics relating to his new book How Music Works. The informal discussion was facilitated by host Dave Haslam and contributor Mark Mulligan, writer of the renowned Music Industry blog.

This was one of only three dates on Byrne’s own version of the traditional book tour entitled Plug In, Tune Out. Each date featured different guest speakers and a different over-arching topic. The Manchester theme for the Manchester leg was ‘Does music matter less in the current era?’

The Beatles, The Stones, Dylan, James Brown... It doesn’t matter who it was it told me there was another world out there and another way of thinking and the sound of it conveyed an attitude I hadn’t heard in my parents' record collection

The opening five minutes were given solely to Mulligan who gave a short presentation on new models of determining artist success in the digital age to ease the audience into the tone and direction for the evening’s discussion.

The Scottish born Byrne took the centre stage seat in the RNCM theatre and appeared utterly relaxed and at ease in his lecturer-like role. The stage lights reflected off his white hair, making him the centre of attention if he hadn’t been beforehand.

How Music WorksAfter a short couple of anecdotes, including Byrne’s ‘method singing’ on the song Drugs (running around the studio so he was out of breath when he sang) the trio found their conversational rhythm for proceedings and hit upon the first musical discussion based on ‘current era’ quandaries. Namely, Spotify.

How Music WorksAfter a short couple of anecdotes, including Byrne’s ‘method singing’ on the song Drugs (running around the studio so he was out of breath when he sang) the trio found their conversational rhythm for proceedings and hit upon the first musical discussion based on ‘current era’ quandaries. Namely, Spotify.

Byrne admitted to tracking his Spotify-related royalty income out of curiosity: “I picked the song Lazy to see how it was doing in Europe. The total income was around £400 divided by myself and DJs and from that there was 15% after record label agreements. In the end I was left with lunch money. That was over a year so I earned one lunch that year, but that’s not to blame Spotify – that’s too easy.”

Mulligan followed up with some industry facts and figures of his own revealing that it takes around 300 Spotify plays of a song to equate the same income from one iTunes download of the same song. The same is true of that song receiving just one play on mainstream radio with around 5000 listeners.

The trio offered little in the way of solutions or alternatives for artists but they were also careful to not come across as angry at the current recorded music consumer trends. This was a civilised discussion pointing out intriguing issues in the music industry in a post-internet world rather than an attempt at starting a copyright witch-hunt.

Staying true to the theme of the evening – Does music matter less in the current era – Byrne and Mulligan discussed the curious shift in music related technology after the advent of the internet. The pair mused on how previous technologies had been focused on creating better sound quality, moving from cassette to CD and dabbling with minidiscs etc. Currently however they claimed that technology was focused on music quantity rather than quality, with people valuing their consumption of all songs over the quality of them.

Whilst the panel jointly bemoaned this trend they conceded to the mp3/iPod age’s ease of use. Byrne also went further to muse that fan-to-fan relationships faded through technology allowing all songs to be immediately available via a laptop rather than the romanticised act of swapping mix tapes and personal recommendations.

On the other hand artist-to-fan relationships have increased through Twitter and other social networking platforms and the need for artists to self promote to generate an income.

Manc DJ turned ‘journalist’ Dave Haslam seemed a bit too glued to his pre-planned questions which were often more like sweeping gloom-ridden nostalgic statements in the vein of “Where’s the next Hendrix/Lennon/Cobain?” Given the innovative and progressive presence of Byrne this line of questioning only served to frustrate the ideas and theories of How Music Works.

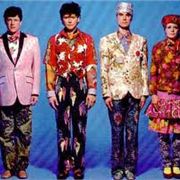

One of the more interesting segues was the discussion of the broader description of pop music from the sixties to now. With a career that spanned the majority of the last few decades Byrne mused that for all the industry changes pop music has changed very little in sound over the past fifty years. Where before the pop explosion popular music consisted primarily of big band material, the new music signalled a radical departure, the likes of which has not occurred since.

Talking HeadsCould this change ever occur again? The trend now is for genres to assimilate one another – punk, pop-punk, punk-rock, etc. Even the most radical new records are described by their assumed influences.

Talking HeadsCould this change ever occur again? The trend now is for genres to assimilate one another – punk, pop-punk, punk-rock, etc. Even the most radical new records are described by their assumed influences.

“To me the James Blake record was pretty radical, it was so stripped out and there were barely any words. But I doubt something like that will start a million other records like it,” said Bryne.

The latter half of the evening was dedicated to questions from the audience to which the house lights were turned up to reveal a sea of up-stretched eager arms. Byrne’s only request was that the “questions be asked in the form of a question” which was not always heeded.

A couple of times long convoluted and muddling statements expecting answers stumped Byrne as they would have anyone, but the final question from a twelve year old girl ended the night on a particularly sweet note.

The girl simply asked Byrne what music he listened to when he was twelve, the kind of simple prompting question that allowed his passions to spill forth: “The Beatles, The Stones, Dylan, James Brown... It doesn’t matter who it was it told me there was another world out there and another way of thinking and the sound of it conveyed an attitude I hadn’t heard in my parents' record collection.” he replied.

It is this other way of thinking that fills the pages of How Music Works. It’s just a pity these ideas didn’t quite come across on the night.

Follow Ben Robinson on Twitter @BenPRobinson.