CHURCH towers, chimneys and tower blocks.

We're talking about Manchester's skyline which is now set to start leaping unlike ever before

First religion drove us to heaven, then industry filled the skies with smoke, commerce took over and now it appears we want to live closer to the gods

All the action has come in the last 250 years as far as tall buildings are concerned.

Aside from relatively modest church towers, nothing much troubled the Lancashire skies over the small town until industry came barging down the road, swaggering like a king, changing everything.

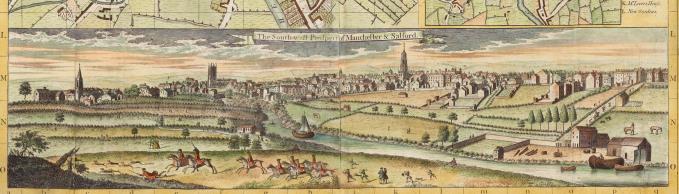

The earliest skyline views we have of the city are from the south west, the present Liverpool Road area of Salford.

And look at the cute place in this 1750 illustration from John Berry's map.

Manchester around 1750

Manchester around 1750 There are just three tall structures, from the left, Sacred Trinity, Manchester Cathedral (at that time called the Collegiate church) and St Ann's. The Cathedral tower from the 1420s was the oldest and tallest and the first structure to climb over 30m (100ft).

Meanwhile a fresh salmon-rich River Irwell snakes across the foreground with the old quay on the right. Quay Street in the city centre marks this former landmark. Big houses with posh gardens and summer houses occupy Spinningfields. Estimates vary as to the populaton size but it can't be much above 20,000. Yet fortunes are being made in trade and Manchester is already famous for its textiles.

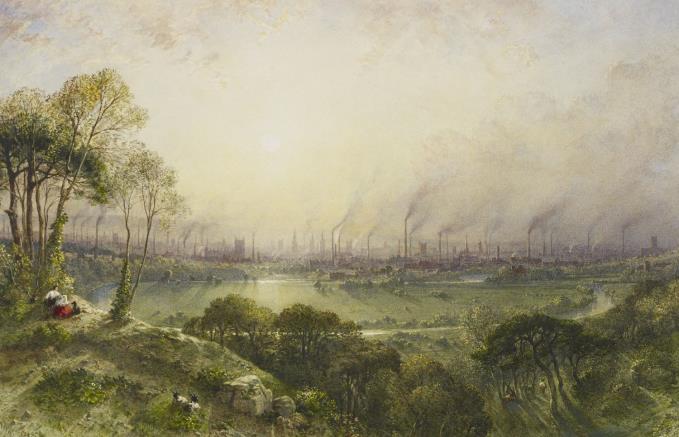

A century later and all is utterly changed. The world has been remade. Manchester has become a famous metropolis, the 'shock city of the age' and is filled with tall structures. One German commentator has already exclaimed how Manchester has become the first city in the world where chimneys are taller than churches and palaces.

This 1850s' view of Manchester from Kersal by William Wyld captures the transformation.

The world is changed: William Wyld's 1852 painting with the horizon filled with high chimneys

The world is changed: William Wyld's 1852 painting with the horizon filled with high chimneysIn the foreground there's a typical depiction of a rural idyll complete with lolling farm workers and splendid nature. It could be any pastoral of the period from across Europe. But behind is Manchester with one of the tallest skylines in Europe, a forest of chimneys with churches glimpsed between. Industry has arrived and the 1750s town has been blown away. It's a transitional moment perfectly caught, the foreground is the past, the background the future.

The sheer energy of Manchester is captured again in this view taken as though from a hot air balloon in the 1859. It's by John Raphael Isaac and views Manchester from high above Salford Crescent.

John Raphael Isaac's 1859 view

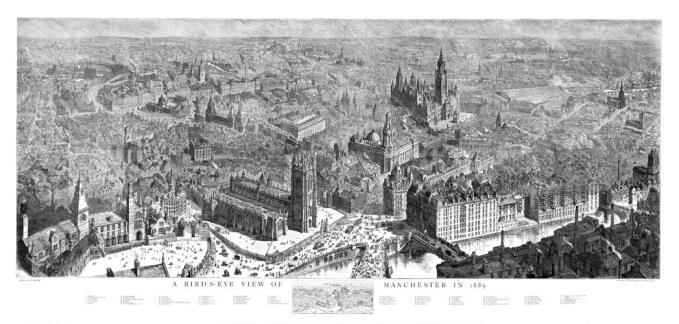

John Raphael Isaac's 1859 view In 1889 H W Brewer in The Graphic magazine again imagined the city from a high perspective. The chimneys are still ever present but this time the skyline is more familiar. The Town Hall is ten years old, the Cathedral tower is six metres (20ft) higher than in the 1750s picture after restoration, and the Royal Exchange tower on Market Street has arrived.

H W Brewer's 1889 bird's eye view

H W Brewer's 1889 bird's eye viewThe next exponential lurch upwards came with the building boom that followed the opening of the Manchester Ship Canal in 1894. Commercial properties such as St James' Buildings and the Refuge Asssurance now built over on iron frames lifted the city. In this same family of structures were more commercial properties from the 1920s and 1930s such as Ship Canal House, the Midland Bank, Sunlight House and many more. These were often over 50m (165ft). The triumph of the chimney was over.

St James' Building and The Refuge Assurance (now The Palace Hotel)

St James' Building and The Refuge Assurance (now The Palace Hotel) Ship Canal House

Ship Canal HouseThe scale of these early twentieth century buildings created much debate in the city. Did we want to ape Chicago, one letter to the Manchester Guardian disapprovingly asked? The controversy resulted in permission being refused for two buildings that would have greatly enhanced the present skyline: Lee House and Memorial Tower. The first, set to be completed before the outbreak of WWII, would have been over 76m (250ft), the second, proposed shortly after WWII, would have been over 115m (380ft). The first stage of Lee House was completed but Memorial Tower never got started.

Lee House at 250ft and a beautiful design

Lee House at 250ft and a beautiful design Memorial Tower standing at 380ft behind Sunlight House

Memorial Tower standing at 380ft behind Sunlight House The International Modern movement in architecture brought the first true skyscraper to Manchester with the 118m (390ft) CIS tower in 1962. This was followed by the 107m (350ft) Sunley Tower (now City Tower in Piccadilly Gardens) and a rash of tall office buildings.

The period after World War II also saw the mass demolition of the chimneys that had punctuated the nineteenth century skyline. The fall of the chimneys led, it could be argued, to a lower profile of buildings across the city generally, although this was compensated through the late sixties and seventies by the rise of the suburban block of flats .

The CIS Tower

The CIS Tower The CIS Tower was top dog for a remarkably long time, 44 years, until in 2006 Beetham Tower overwhelmed it. At 169m (554ft) it produced a lopsided skyline for the city; a skyline pinned at one end by the CIS Tower and at the other by Beetham Tower.

Lopsided skyline from Chester Road

Lopsided skyline from Chester Road

The present view from Old Trafford

The present view from Old Trafford Another recent view taken from a similar location to the 1750 prospect above

Another recent view taken from a similar location to the 1750 prospect above The international financial crisis of 2007/8 put paid to competitors for Beeetham Tower. But ten years on the property market is swilling with cash and the skyline of Manchester city centre, with that part of Salford contiguous to it, is destined to leap higher than ever before. This time with residential towers. Our article here shows several visualisations of how that skyline is set to change and includes Owen Street Tower, which will be the first to break 200m (650ft).

Some of these projects won't happen, but many will.

They are part of the continuing story of the city's silhouette and how changing requirements produce patterns in the production of tall buildings.

First religion drove us to heaven, then industry filled the skies with smoke, commerce took over and now it appears we want to live closer to the gods.

Blue-sky thinking so to speak.