SET IN Italy during the seventies, a period of continuing economic crises and rampant inflation, the story takes its inspiration from autoriduzione movements which saw Italian working people take control of the prices they paid for food, transport, rent and utilities.

From the start it’s slow, sluggish, and a little too shouty. Characters spend too much time staggered and bemused by their own choices for the farce to take hold.

Working class Italian housewife Antonia has joined in a housewives protest at the local supermarket where they shopped paying only what they thought was a fair price, or only what they could afford.

Antonia has a substantial amount of shopping which she needs to hide from her scrupulously honest husband Giovanni. She enrols the help of friend and neighbour the recently married Margherita. Their attempts to smuggle food out of the house under Margherita’s coat are explained to Giovanni as pregnancy, a fairly rapidly developing pregnancy at that, and an ambulance is called.

Margherita’s husband, Luigi, is overjoyed at the news and the two men dash off to hospital pursued by police seeking the ‘stolen’ supermarket goods.

A controversial 1997 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Fo uses the daft plot to pursue discussions of exploitation, working-class solidarity, profiteering, political betrayal, and the early days of a twentieth century feminist revival.

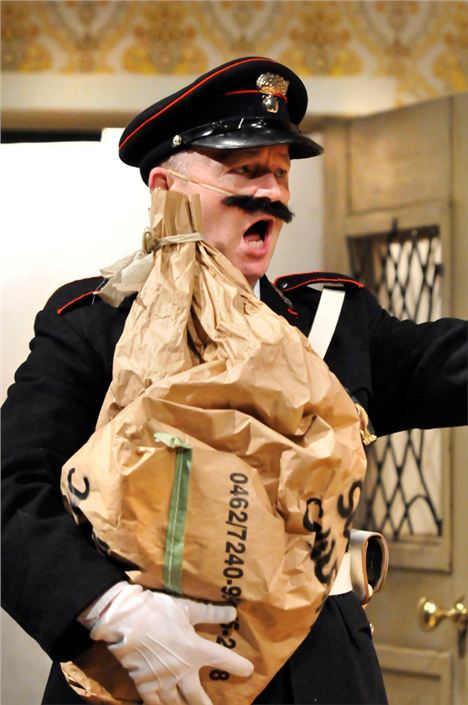

His work is essentially farce, with traces of Italy’s Commedia dell'Arte, a style seen on the British stage in Richard Bean’s recent hit ‘One Man, Two Guvnors’. Fo can be just as funny, but with added a political bite.

The Octagon production chooses to retain the original location, place and time, rather than update or move to the UK. The costumes and the wallpaper, together with the rather shabby kitchen and paucity of household consumer goods, gets that just right.

But the play loses its fire and pace, and therefore its comedy, in this production. The political message is weakened too.

An updated version might have captivated the audience more. Times have changed since I first saw this play. In those days it was believed that profitable businesses paid taxes, and that high prices were a result of high costs, rather than a deliberate part of the marketing mix.

I doubt Dario Fo would mind a little tinkering to reflect modern times and to put the boot into bankers again. An updating of the political context too would not have gone amiss; some of the play’s references to splits within the left are lost on large parts of a modern audience, many of whom might even find reference to shop stewards a little confusing. These things were much more common currency in the seventies.

But even an updating wouldn’t work without a change from the performance style and pace delivered at Bolton.

From the start it’s slow, sluggish, and a little too shouty. Characters spend too much time staggered and bemused by their own choices for the farce to take hold. Farce needs a good percentage of straight playing characters apparently blissfully unaware of the nonsense of their acts displaying a convincing belief in their own rationality.

The audience can provide the interpretation, questioning the action until overtaken by the twisted logic and laughing in spite of themselves.

Colin Connor is closest to this, playing a rather effete and lovable Giovanni with a charming Irish accent and a great stage presence. Danny Cunningham, as Luigi, conveys a genuine delight at news of his wife’ imminent confinement, despite there being no sign of her pregnancy just a few hours previously.

Eamonn Riley has the most fun in assorted roles, including two almost identical policemen. Kate Coogan, who displayed superb comic timing in the Octagon’s award-winning Secret Thoughts, has limited opportunities to shine. Lynda Rooke is a strong force, but it is difficult to believe how in awe of her husband she is, and her pace is too slow.

The Octagon had not originally programmed Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay, but scheduled it to replace a new work Stitched Up’, which was not quite ready. Bolton Octagon has produced superb work in recent years, but this production doesn’t reach their core standards.

Can’t Pay Won’t Pay is at Bolton Octagon until Saturday 18 May