IT’S becoming an anguished cry for those interested in Manchester’s soaring profile: Why aren’t our proposed new towers and skyscrapers more flamboyant?

Manchester wouldn’t suit that Dubai style of architecture, I don't think many places do...

People look to work across the world in Shanghai or Dubai or closer to home in London with The Shard and The Gherkin and say, why not here? Recent comments about the plethora of new development proposals on Confidential have included: ‘Why do all these have to look like Square blocks?’ or ‘Horrific soulless boring blocks, Londoners will be laughing looking at these’ or ‘I wish the designs were a bit more interesting. Why is every single one just another boring cuboid like the 60s tower blocks?’

Of course ranters on websites often hit the keyboard after spending no more than three seconds thinking about their target. Still, the lament is commonly heard, hinting at a split between many in the profession, apart from a few 'starchitects', and general public opinion.

As Nicolai Ouroussoff, has written in The New York Times: ‘The current mania for flamboyant skyscrapers has been a mixed blessing for architecture. While it has yielded a stunning outburst of creativity, it has also created an atmosphere in which novelty is often prized over innovation. At times it’s as if the architects were dog owners proudly parading their poodles in front of a frivolous audience.’

The poodles Ouroussoff refers to are often the essence of vanity and ego, the corporate monsters of ‘new money’ economies in the Middle East and Asia, now of course, spending big in London. Sometimes these are blatant expressions by the same countries of their arrival on the global scene. Nothing new in this of course, Manchester Town Hall was a demonstration of civic muscle in 1877 and proof of its place in the world, walk through Whitehall and that's all about Imperial Britain.

Last week in Manchester, Childs Graddon and Lewis (CGL) revealed revised plans for the Trinity Islands apartment scheme close to St John’s and Castlefield. The highest tower had been reduced in height from 50 to 38 storeys and some of the original, more spectacular ideas, such as rooftop gardens crowning the development, have been lost. Down at the podium and ground-level really attractive elements remain: gardens, internal courtyards, a running track, River Irwell views and so forth, but cold reality had stormed in and scaled the scheme's height down, although the same number of flats (around 1,200) will be built.

The original Trinity Islands design

The original Trinity Islands design The new proposal - toned down but apparently 'multi-coloured'

The new proposal - toned down but apparently 'multi-coloured'One of the problems was that initial consultation had revealed concerns about the tallest tower overwhelming the nearby Museum of Science and Industry and the Grade I listed Liverpool and Manchester Railway Station. This demonstrates one of the issues facing tall buildings in the UK, it can be harder in a democracy to push schemes through than within autocracies. Although the fact that consultation lowered this scheme might be something campaigners against Gary Neville's black towers by the Town Hall could use as ammunition.

Not that the Trinity Islands towers have been reduced to simple rectangular blocks without ambition. The footplates are rhomboids and the walls are alive with colour patterns that will shift as a person moves round the buildings. The structures will look subtle when viewed straight on, but the ‘colour becomes more intense as the viewing angle becomes more acute’.

Just don't expect any 'iconic' tall building of shimmering, twisting glass or steel pirouetting into the pure blue of the Manchester sky. Or maybe the grey.

Model ambition from Gary Neville's consortium muscling in on Albert Square

Model ambition from Gary Neville's consortium muscling in on Albert Square“Manchester wouldn’t suit that Dubai style of architecture, I don't think many places do,” says Roger Stephenson, a busy Manchester architect whose best building in the city is, in my opinion, the new Chetham’s School of Music opposite Victoria Station. “And anyway the problem is money, especially with apartment blocks. Even if we wanted to make them more flamboyant, the return you can get from selling apartments in say SimpsonHaugh’s One Blackfriars in London is unimaginably higher than any return you can get in Manchester.

“But what we can aim for here is to deliver polite, well-managed towers that display excellent design and good discipline. There are architects who work well and with imagination when working at a traditional scale who maybe get it wrong with towers. I think that when we work on the higher levels of towers we need to follow the function of the building rather than attempting to make them more interesting forms purely for cosmetic reasons. If you do that things can look poor and cheap. That's not to say it can't be achieved, you just have to be careful.”

For the record a three bedroom apartment high on the 42nd floor at Beetham Tower recently sold for £750,000. In One Blackfriars in London, a three bedroom apartment is £3.38m, and that's not even in the posh top part of the building, which in turn is not in the most expensive part of London. That's five times more than in Manchester's most prestigious tall building. Thus relative values indicate how much more money SimpsonHaugh, the Manchester practice who designed both towers, had to play with in London. By the way, the most expensive penthouse in One Blackfriars is being marketed at £23m. You heard.

Beetham Tower animated by sunset

Beetham Tower animated by sunset London's One Blackfriars animated by a bigger budget

London's One Blackfriars animated by a bigger budgetPhil O’Dwyer from OMI architects, a practice involved in tall buildings such as One Greengate in Salford, agrees on the point about price and quality.

“The amount of exuberance you can display is down to money, so when there isn’t too much to play with you have to work harder to enliven the design,” he says. “When you are subjected to development pressures it might be nice to have different uses to justify changing the form as the building climbs, but if there isn’t financial viability then that becomes difficult.

“I believe strongly that where it does make sense within a design, then high level variety should be attempted,” he continues. “There’s one school of thought that the pure Miesian tower (named after German architect Mies van der Rohe - think of Manchester's CIS tower) with its careful detailing and perfectly honed enclosure, giving an expression of what’s going on inside, is the correct way. I don’t agree. The danger with the simple box is that it makes no connection with people, it’s dumb, doesn’t talk to them. There should be something happening at the higher levels of a building that makes a connection at some distance away, and then when that building meets the ground there should be something happening again. But this is where money comes in, if there is no change of function towards the top of buildings then it can make no sense to impose one.”

Dave McCall, O'Dwyer's business partner at OMI, adds a further element: "We are being presented with an opportunity to transform our city and dramatically increase the population, getting much closer to the density of successful European cities. We should of course always seek to tease the most out of any development site and use every opportunity to extend the positive influence of regeneration on the adjacent streets. Every site is unique and it is how we embrace the context that will give our new buildings a relevance and purpose."

What we don’t need are any more mess-ups, such as the total shambles that is the 'Green Quarter' or the Great Northern Tower

Context, relevance, function.

Professional architects are not trained to think about providing flights of fancy for flights of fancy's sake. They feel dirty, unless the fee is right, I’m guessing, talking about what has become known as 'vanity height'. This is where architects, get their special effects by adding a bit at the top of a building with no active use, which might be solely designed to make a building taller or give it a racier profile. Thus 20% of the Shard’s height in London is ‘vanity height’, that’s more than 60m - about the same height as Manchester's Palace Hotel tower.

Personally I would take Stephenson's ‘polite and well-managed’ over hyperbole, or as Phil O’Dwyer describes, ‘the indulgence’ of Dubai, any day. Spare my city that type of deranged and frequently self-indulgent Bladerunner landscape full of shouty skyscrapers and controlled private spaces. In that case it’s a shame that Gary Neville’s St Michael’s towers will shade Albert Square rather than sit somewhere along the inner ring road where they would add variety of form.

But planning and policy is part of the problem. Manchester and Salford councils treat cases individually and appear to ask for changes here or there to schemes, but miss the big picture in terms of context and the long term viability of the structure within the street scene. A classic contradiction will come into play if the St Michael’s towers are given planning permission, when a decade or so ago permission was refused for tall buildings on Peter Street because they were too close to the Town Hall. Peter Street, remember, is further from the Town Hall than St Michael’s.

Not that our dear authorites don't come up trumps, St Peter's Square is beginning to look spectacular. And we have good examples of high buildings in Manchester, often with interesting profiles: One St Peter’s Square by Glen Howells Architects; the Civil Justice Centre from Denton Corker Marshall; 17 New Wakefield Street (although I would have preferred another material to the grey panels) by Hodder+Partners; One Angel Square by 3DReid; Urbis by SimpsonHaugh, and Parkway Gate by the same practice. I adore the discipline of 5Plus Architects’ 10-12 Whitworth Street proposal and the compact and satisfying design of the St George’s Island towers from OMI.

One St Peter's Square is tall and beautiful

One St Peter's Square is tall and beautiful 5Plus Architect's dignified Whitworth Street proposal

5Plus Architect's dignified Whitworth Street proposal

Of course, it’s telling that most of these are commercial or civic buildings which had big budgets. It’s also telling, as mentioned, that most of them are less than 20 storeys and given their profile aren't strictly tall. Roger Stephenson might be right, let’s keep things down but increase the quality, maybe 20 storeys is a good measure. I love tall towers, they make me excited, but maybe we’re better working lower down. One building that certainly seems capable of setting the pulse racing for architecture lovers will be Koolhaas's controversial £110m Factory (click here). But it won't be especially tall, though it will be big.

Manchester and Salford within Trinity Way will not be looking anything like Shanghai in the near future, but should we gain a cityscape on the central fringe of ‘polite and well-managed’ towers then we will be lucky. What we don’t want are repeats of so much of the tacky, cheap looking towers of recent times. What we don’t need are any more mess-ups, such as the total shambles that is the 'Green Quarter' or the Great Northern Tower. Let's hope CGL's colour-shifting sky towers improve the central Manchester climbing skyline. So with residential towers, unless budgets get much bigger, I'd say, be careful what you wish for.

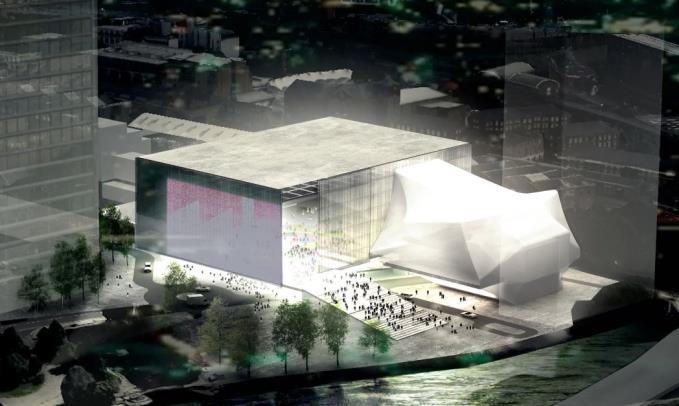

Koolhaas's Factory by the banks of the Irwell

Koolhaas's Factory by the banks of the Irwell

Powered by Wakelet

Powered by Wakelet