SINCE time immemorial, so-called ‘second-class’ citizens have had to contend with an exclusive social hierarchy that favours men of a certain status.

There are simply too many tenacious, inspirational women in Manchester history to be marked with one statue

The tragic 1819 Peterloo Massacre, for example, was prompted by votes being restricted to less than 2% of British men. Working class males were excluded and women, needless to say, weren’t even a consideration until shopkeeper Lily Maxwell was mistakenly included on the Register of Electors almost 50 years later. This was due to the passing of the 1867 Reform Act, which allowed one million more men to vote, provided they met the (again elitist) property requirements. What the act failed to specify was that women who met these requirements still weren’t eligible, leading to Maxwell’s inclusion and making her the first woman to vote in a municipal election.

Ultimately, however, Maxwell’s vote was disallowed: like much of history, it was one small step for ‘mankind’, two steps back for ‘womankind’. And so began Manchester suffragettes’ struggle towards gender equality.

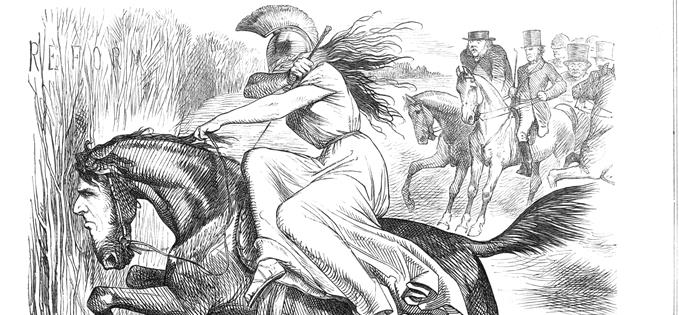

Punch magazine called the Reform Act a leap in the dark

Punch magazine called the Reform Act a leap in the darkFollowing her injustice, Maxwell campaigned with leading activist Lydia Becker to persuade 5,300 other women to add their names to the electoral role, resulting in a court case named ‘Chorlton v Lings’. Barrister Richard Pankhurst, husband of Emmeline, appeared on the women’s behalf but they lost their case when the law found them to be ‘personally incapable’; a viewpoint which also meant women were exempt from many professions. Subsequent protests involved bombing Alexandra Park’s beloved cactus house, damaging pictures in Manchester Art Gallery and attacking post boxes with black liquid.

The ‘outrages’ were part of a series of protests against the 1913 arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union - the foremost suffrage movement - for her part in a bombing at a house being built for politician David Lloyd George. She was released on special licence after ten days and taken to a nursing home, having refused to eat. Interestingly, she avoided the brutal force feeding suffered by fellow suffragettes, perhaps due to the potential backlash and maybe because she was middle-class.

The Pankhurst home is now a suffrage museum

The Pankhurst home is now a suffrage museumEmmeline’s daughter Christabel also played an active role in women’s liberation, most famously at a 1905 Liberal meeting in the Free Trade Hall (now Radisson Blu Edwardian Hotel), when her and factory girl Annie Kenney unfurled a banner asking ‘Will the Liberal government give votes to women?’ She was ignored, prompting her to repeat the question and the meeting descended into chaos. Arrested for spitting in a policeman’s face, Pankhurst - along with Kenney - chose imprisonment at Strangeways Gaol instead of a fine.

So begun a period of militant action which continued until after WW1. It was not until the Equal Franchise Act in 1928 (although women over 30 had been given the right to vote in 1918), however, that women finally achieved voting parity with men: the first in a series of breakthroughs for UK suffragettes. Despite this, gender stereotypes prevailed and, whilst the Equal Pay Act followed in 1970, women still receive almost 20% less than their male colleagues even today.

The Sex Discrimination Act followed in 1975, meaning females could access industries and institutions that were previously unavailable. A ‘second wave’ of the women’s rights movement, which continued into the 1980s, saw the founding of organisations like Manchester Rape Crisis and subsequently Manchester Justice for Women; as well as literature that challenged preconceptions and publishing initiatives like Spare Rib, Shocking Pink and Virago Press.

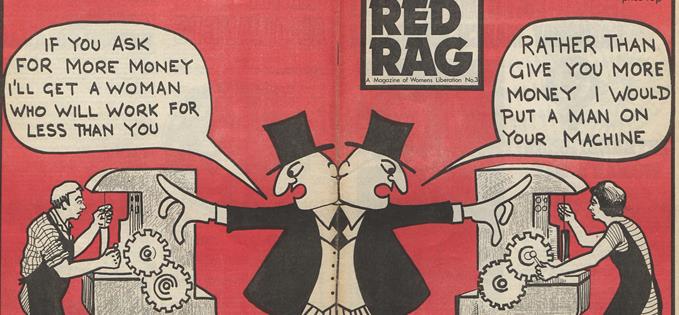

Red Rag was a key feminist publication

Red Rag was a key feminist publicationIn 2010, the unified Equality Act was passed, which protects against discrimination based on any one of nine characteristics: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation. This signifies a major change in attitudes, not only for women but for many groups that have faced prejudice for centuries: something for which the suffragettes campaigned so tirelessly - and for which women in many countries are still fighting.

Indeed, despite these promising signs of progress, men are still placed on a pedestal and the World Economic Forum has predicted that it will take until 2133 to achieve global gender equality. Although this is widely down to non-Western cultures, even Britain is guilty in many respects; alarmingly, we are 26th in the Global Gender Gap Report due to factors like the lack of women in positions of leadership and continuing discrepancies in pay although in other counts we do far better.

Such issues make International Women’s Day relevant. Whilst some countries have celebrated a form of IWD since the early 1900s, it only became an official UN celebration in 1975 (a full timeline can be seen here), with interesting implications for 2016 and beyond.

Aptly, this year’s theme is ‘Pledge for Parity’, with worldwide celebrations including a Tanzanian hockey match, New Delhi cycling rally, Palestinian festival and, of course, a Google doodle. The United Nations has also published a beautiful timeline celebrating iconic females throughout history. Closer to home, Manchester celebrations include the Wonder Women Festival and a diverse programme on the theme of ‘Women’s Voices’.

A UN conference will reflect on how to achieve Planet 50-50 by 2030

A UN conference will reflect on how to achieve Planet 50-50 by 2030Earlier this year, the vote for a new statue of a woman in Manchester, due to be unveiled on IWD 2017, revealed suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst to be the undisputed favourite - leading Confidential's Jonathan Schofield to question whether it should have been the aforementioned Lydia Becker. The fact that Becker, founder of the Women’s Suffrage Journal and a key player in women’s liberation, didn’t even make the shortlist shows there are simply too many tenacious, inspirational women in Manchester history to be marked with one statue. As Jonathan said, let’s hope that Pankhurst is just the start and, eventually, we will see a city - ultimately a world - with as many celebrated females as men.