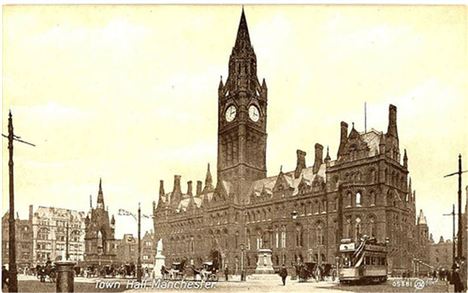

IF THE city has a local architectural icon it is Manchester Town Hall tower and spire.

The solid, restrained Gothic flamboyance of the 288ft tower is etched on the mind’s eye of every passing Mancunian. In a city with a developing skyline, it’s the lodestone, the solid bond between Victorian past and uncertain present.

Despite all the fancy detail, the gargoyles, the curlicues and finials, there's no more solid space in Manchester. This was one of the key qualities of Alfred Waterhouse. He was the master of the robust.

But we're lucky to have it.

And the one we nearly got was terrible.

The architect of both towers, the actual one and the proposed one, was Alfred Waterhouse. He's renowned for many city and UK buildings – the University, Strangeways Prison and the Natural History Museum in London.

Waterhouse was largely unknown in the city where he made his reputation until pub chain Wetherspoons came along and named a boozer on Princess Street after him. This is amusing because, as a Quaker, Waterhouse scarcely, if ever, drunk the demon drink.

Given that he built so much of Manchester it's also vaguely amusing that he was a Scouser.

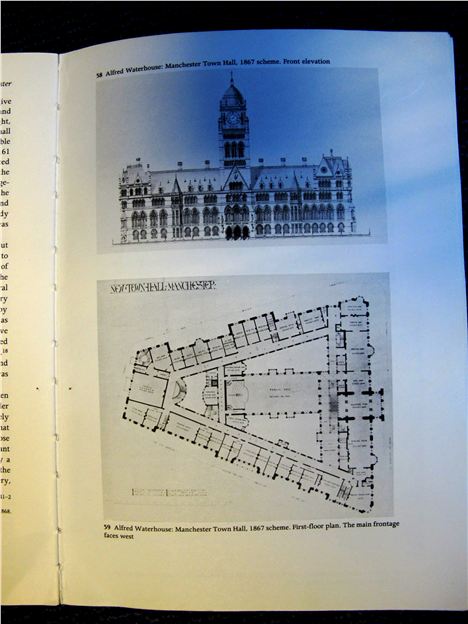

He seems to have entered the 1867 competition to design Manchester Town Hall late and in a rush. This explains why in terms of looks his design came fourth. But in its practical use of the awkward triangular site and its internal arrangement it won hands down. Ever practical, the Victorian mindset dictated that the most useful not the most fanciful design should be chosen. It probably wasn't that way with Urbis.

The big problem with Waterhouse's proposal was the whole arrangement of the tower, spire and entrance. The judges did the equivalent of tapping their finger on the drawings and saying, “Alfie, boy, that’s crap, you’ll have to change it.”

Must try harder - image taken from the magnificent 'Art and Architecture in Victorian Manchester' edited by John Archer

Must try harder - image taken from the magnificent 'Art and Architecture in Victorian Manchester' edited by John Archer

It was bloody awful too. Look at our picture above: that strange dome thing on the top is a weedy weak thing, as though Waterhouse had scribbled it in 15 minutes before the handing-in deadline.

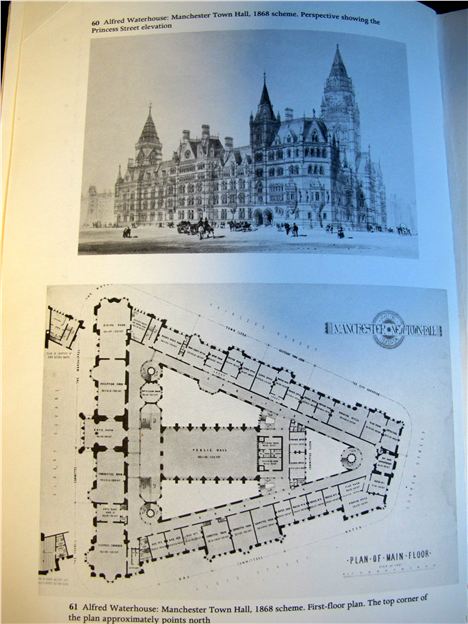

So he drew it again and produced a proper pointy spire. Then he reduced the heaviness of the spire by drawing it as a filigree of delicate stone tracery. Still unhappy with this latest solution he finally redrew it with the spire we see today, punched with four leaf 'quatrefoil' holes.

Still not quite there - image taken from the magnificent 'Art and Architecture in Victorian Manchester' edited by John Archer

Still not quite there - image taken from the magnificent 'Art and Architecture in Victorian Manchester' edited by John Archer

But something kept nagging at him and six years into construction as the Town Hall neared completion, he suspended work. He called the building committee together and explained that the proportions were still wrong and the tower needed to be 16ft higher. The committee agreed.

The entrance to the tower and the building was annoying him too. He finally settled on a large openwork screen over the entrance which made the latter look bigger and more in proportion with the tower above. It also cleverly reflected the shape in plan of the Town Hall and was capped off with a sculpture of the Roman general Agricola who founded Manchester. Thus the entrance to the Town Hall marks the origin (the entrance into history) of the city. Neat.

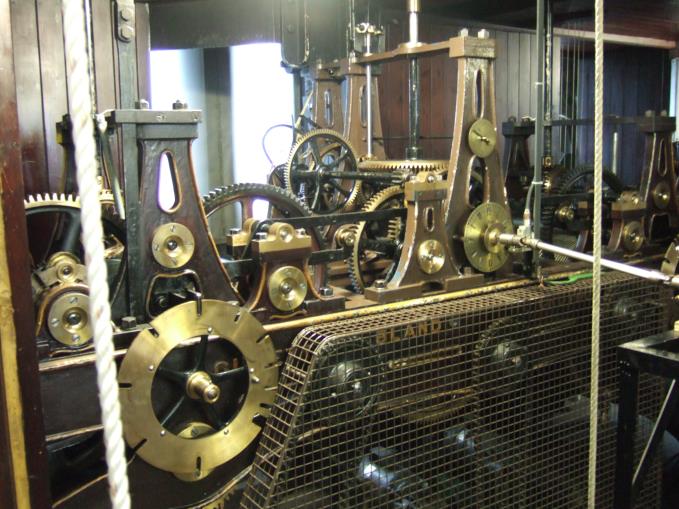

We've taken Confidential readers up to the top of the tower. On the trip there were many joys. A highlight was the room where the original clock mechanism resides. This is a phantasmagoria of immense brass wheels with clunky levers and gears clicking and whirring. Higher again is the chamber behind the clock faces, with the 6ft hour and 9ft minute hands silhouetted against the sky.

From the balcony the views north, south, east and west are superb. Despite all the fancy detail, the gargoyles, the curlicues and finials, there's no more solid space in Manchester. This was one of the key qualities of Alfred Waterhouse. He was the master of the robust. He could do fancy when required but his talent lay in solidity, making buildings that feel as though they will never fall down. When you’re 200ft up, that’s a valuable quality.

Andrew Brooks famous image from Manchester Town Hall Tower

Andrew Brooks famous image from Manchester Town Hall Tower

On three sides the protruding gables above the clocks bear two words each picked out in gold. Together these read, 'Teach Us To Number Our Days', a Biblical quote advising us to make the most of our lives.

The main lantern chamber holds Great Abel, the hour bell of Manchester Town Hall, which is bigger than a generous three-man tent and is named after the mayor at the time of opening – Abel Heywood. Cast round the top are lines from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem ‘In Memoriam’. They read ‘Ring out the false, ring in the true.'

A worthy sentiment but one to make a journalist's eyes water.

For a listen to the Town Hall bells click here.

This article was first posted 12/8/2008 and has been re-edited.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+