WE'VE been looking at maps

Manchester and Salford are interesting towns in 1750 but they are a step away from greatness

The maps Confidential has been looking at come from the good people at Manchester Central Library's archives section.

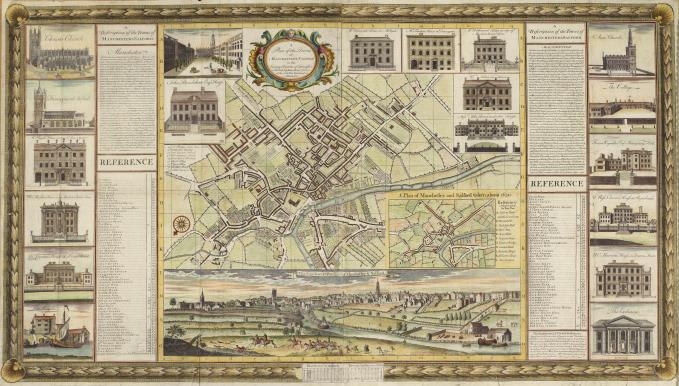

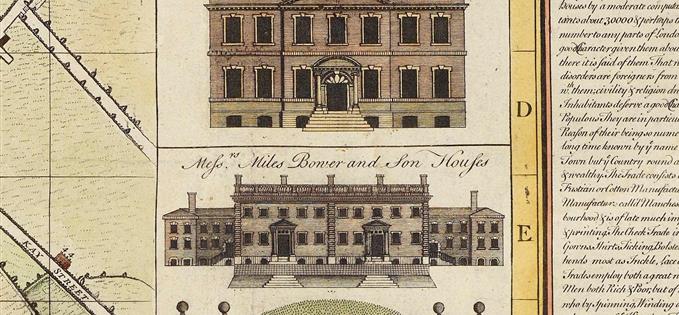

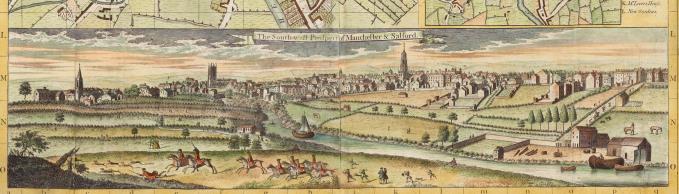

The main image above comes from the remarkable John Berry map, complete with description and images of the town, from 1750.

The document claims a population figure of 30,000 for Manchester but now this figure is considered too high, maybe a little under 20,000 is more correct.

The map and picture shows the quiet before the storm. The town already has a reputation for textiles, but the processes are still water-powered or man-powered. The full mechanisation of industry, its power to transform production, to rip raw materials from the landscape, to fill the sky with smoke is just over the horizon. Manchester will of course be the first urban manifestation of that world-changing moment.

So while Manchester and Salford are interesting towns in 1750 they are a still step away from greatness and notoriety - a terrible greatness maybe with worldwide repercussions but greatness all the same.

For a clue to what a mighty international centre of pioneering achievement they would become click here.

Yet fortunes are being made already, look at the pictures and you can see the houses of the wealthy that are scattered through the city, some of them almost palaces. Here are the paired mansions of Miles Bower and Sons, standing back from Deansgate, where RBS in Spinningfields now hulks. Behind in Spinningfields there were pleasant gardens with summer houses.

Evidently the gap between super rich and poor was closer in 1750. From the packed impoverished streets around the Cathedral and Withy Grove to the houses of the rich was a five minute walk. Friedrich Engels and others would note in the first half of the nineteenth century, how the well-to-do were moving further and further from the city centre to avoid the poverty and the smoke of the new industrial megalopolis. But here in 1750 that is yet to happen.

Only the three churches are still around today from the 1750s in the view below - Manchester Cathedral is the centre church - and the towers of all three have changed. St Ann's Church on the right has lost its funny little cupola.

Some street patterns survive. Behind the fox hunters above and on the river is a little house which stands close to the Mark Addy pub site. The buildings on the extreme lower right lie at the bottom of Quay Street, spelt Kay Street on the old map.

The 2012 view from more or less the same angle is very different. The old topography seems to have been squashed out and the Cathedral tower is hidden from view. There are no fox hunters, or promenading couples, there are no attractive red sandstone cliffs on the Manchester side close ot the Cathedral.

The only other house on Quay (Kay) Street we can see on the 1750 picture lies on the south side of the street and still hosts a large eighteenth century property. This is Cobden House, built by the Byrom family, and although it dates from probably the 1770s provides a link with that lost quiet world.

And on the next plan below there's site of Manchester Town Hall. From medieval times a triangular meadow had occupied the site and does so in 1750, called South Hall Fields. That shape would dictate the street pattern which would in the end dictate the triangular plan of the present town hall - a charming example of geographical and historical predestination.

These maps are a blast, giving the viewer a glimpse of the way history moves on, and the way the clock never stops ticking. Once Manchester and Salford would have resembled Ludlow or Kirby Lonsdale, towns beloved of Visit Britain promotional campaigns. The Fates had something else in store.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here.

To order or view archive material then click here or here or here.

Town Hall site indicated by triangular meadow

Town Hall site indicated by triangular meadow