Jonathan Schofield thinks the piece might fit better in a gallery rather than on the street

There's no doubt about one thing: Jeremy Deller’s memorial to the Peterloo Massacre is a lively addition to the Manchester street scene.

It is located between Manchester Central and the Midland Hotel, on the site of the renowned pro-democracy meeting in 1819. The work presents a layered mound filled with words and images that turns a cursory glance into a fifteen minute examination. Not many examples of public art do that. Most public art falls into the category of functionless street furniture getting in the way of daily life – that ludicrous cotton bud fountain in St Ann’s Square for instance.

For a piece of a commemorative public art there is just too much of the artist in it

Here’s a three sentence summary of Peterloo for all those people who’ve been on Mars for the last month. On Monday 16 August, 1819, 60-80,000 people from all around the region walked to St Peter’s Fields, Manchester, to peacefully demand the vote and representation in Parliament in a time of great suffering and hardship. The magistrates called in the military, both amateur and professional, to arrest the leaders and disperse the crowd; resulting in the deaths of eighteen men, women and children and more than 700 injured, many severely. It was a hugely symbolic moment on the long road to full British democracy.

The events of that day are represented on the monument in Roman typeface with the names of the dead, the places from which they walked, and images of hands clasped together, laurel wreaths and shuttles; a large proportion of the crowd were handloom weavers. There's a decent metal floor plaque, which is perhaps a bit small, describing Peterloo

Turner prize-winning artist Deller has said: “It’s important for the memorial to not just be something to admire. It has to have a use for the public. It will articulate the story of Peterloo, but will also be a place of meeting and assembly.

“The shape reminds you of the form of a burial mound, a place to commemorate the dead. But the stepped form also means that lots of people can stand and sit on it together. In fact, once a year, on each anniversary of Peterloo, the memorial should almost disappear, as it becomes populated by the public. The memorial effectively acts as a compass – connecting itself not just to the immediate environment close to the Peterloo site, but to Greater Manchester and ultimately the rest of the world.”

A nice touch is that the names of the various places from which people trudged are positioned in correct geographical relation around the monument. Meanwhile the garish colours reflect, apparently, 'various places across the British Empire at the time'. Really?

This is where the problems start. Put simply, the piece, impressive as it is, should be in an art gallery rather than in a public space. For a piece of a commemorative public art there is just too much of the artist in it.

This would be fine if it were to be an entirely abstract work such as the superb Kan Yasuda ‘Touchstone’ twenty metres away outside the Bridgewater Hall, but it isn't. This is a commemoration of the people who lost their lives and were injured in the fight for representative government two hundred years ago. It is publicly funded and has had heaps of consultation involving the city council, Manchester Histories Festival, and the indefatigable and excellent Peterloo Memorial Campaign Group amongst others.

The result is there is a contradiction inherent in the memorial. Art, in many respects, is the antithesis of teamwork. The good stuff is scarcely ever produced by committee, definitely not a municipal one.

Thus, we have the excellent podium and burial mound idea which satisfies the notion of a public commemoration of this nationally significant moment in history. It’s a fine idea, but then Deller wants, as his quote says, us to clamber all over it. People in wheelchairs, of course, can’t do this; so in 2019 a monument about the struggle to represent all the people, doesn’t. There's a 2D version on the adjacent pavement which adds insult to injury. We covered the furore about this here.

It’s a classic case of the vision of an artist working in a public space clashing with what should be the contemporary norm in terms of access. The city council inform Confidential they have come up with a cunning plan to overcome this. That’s going to be interesting.

The second problem concerns Deller’s attempt to go off-piste, and almost put to one-side the commemoration of those eighteen dead and 700 injured from that boiling hot 16 August, 2019 in Manchester. He wants to bring in his own world view.

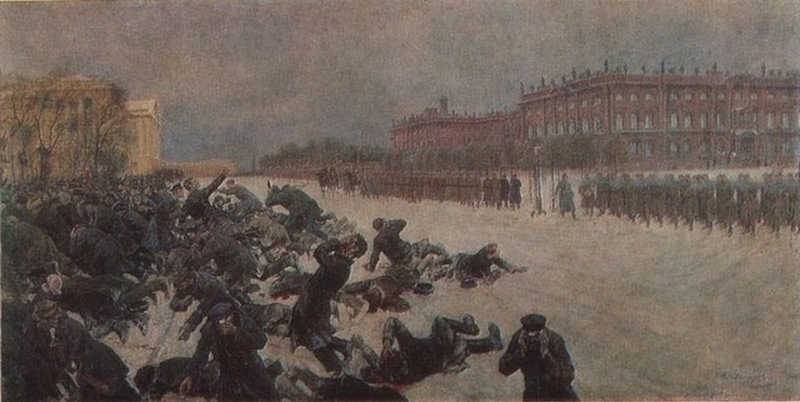

On the top of the memorial is a compass-like installation of arrows pointing to ‘events similar to Peterloo, where peaceful protest has been violently broken up by the state’. It’s a maverick list revealing the prejudices of the artist. He has the classic, art-school hang-up about Britain’s colonial past, thus there’s the Amritsar massacre in India from 1919 and Bloody Sunday, Northern Ireland, 1972. But there’s also massacres featured at the Winter Palace, Russia, 1905, Tiananmen Square, China, 1989, and others in South Africa, France, Poland, Romania, Mexico and the USA. There's no mention of the circumstances behind these.

The weirdly selective list was apparently purely Deller’s choice. Yet if he wanted to record worldwide massacres, then why stop there? The whole memorial could have been covered with similar tragedies in which peaceful crowds were attacked. What about Hungary in 1956, Santa Elmira in Brazil in 1979, the Cairo Squares in 2013? Why are there none from post-colonial India and Pakistan, or south east Asia, elsewhere in Africa aside from apartheid South Africa, what about South America?

Worse, Deller’s list provides no moral equivalence.

Maybe his intention was to prove that the British massacres were part of a route to a solution. Peterloo was a landmark on the path to democracy in the UK; Amritsar revealed British rule in India was arbitrary and independence was inevitable and necessary; Bloody Sunday was a terrible Peterloo-like landmark on the route to the Good Friday Agreement. Maybe, Deller intended that, although we know he intended nothing of the kind, despite the large publicly funded fee he no doubt took from this.

Meanwhile the Winter Palace massacre was part of the route to Stalin, the Gulags, show trials, purges and millions starved to death in Ukraine and across the Soviet Union. Tiananmen Square was a literal dead end in China, which despite the neon glow of its cities, is just as closed to representative government as it was in 1989 - and with its present surveillance systems probably moreso. There is simply no equivalence between cause and effect within his list.

It’s in the remit of an artist pursuing his own art to highlight anything they want and then for us to take or leave it, to make associations or not. That’s fine in the gallery, even possibly with a different piece of public art.

But it is not fine here, the largest public artwork in the city since the ill-fated B of the Bang more than a decade ago.

This piece was, first, second and third, intended to be a memorial to the victims of Peterloo and what their sacrifice meant. Deller’s heavy-handed personal politicising pushes the work too far from the events of 16 August 1819. He should have trusted us to make our own connections. The contradiction between providing a civic memorial by a distinguished, but a very political artist, mars Deller's clever city addition. He makes his narrow, voguish point in an artwork that should be about an eternity of human struggle for representation, into something all about himself. A temporary space in the Whitworth Art Gallery would have sufficed. Peterloo deserved more than such a biased world view.