THIS is a long article, in several chapters. You might want to read it that way, chapter by chapter, and return to it or plough through it all in one go.

It's the start of a series of occasional pieces looking at - in terms of people visiting them - forgotten areas of Greater Manchester which are steeped in history, life and landscape fascination. These are not routes in Tatton Park with waymarked paths and baby-changing facilities, they are routes scarred by post-industrialisation, by fly-tipping, yet they say so much about the way our country and city developed and are developing.

We start just a mile or so north of the CIS Tower in Manchester with a stroll or bike ride down the valley of the River Irk. Practical details of how best to get there if you wish to follow this route are contained in the yellow box at the end of the article.

Jonathan Schofield will be leading a walk along this route on Sunday 15 May - see details below the article or here.

Chapter One - Death, Stone And Plague

WHY did they do these things? Was there no aesthetic sense to what makes a city's identity? Why the needless demolition?

I sometimes wish I could climb inside the heads of planners from the fifties and sixties to work it all out.

Maybe I'd get lost in their neuron networks and find dreams of streets in the sky, an auto-age of shining metal and shiny people in a perfect world. An unreality - something akin to the Earth you see in Star Trek movies.

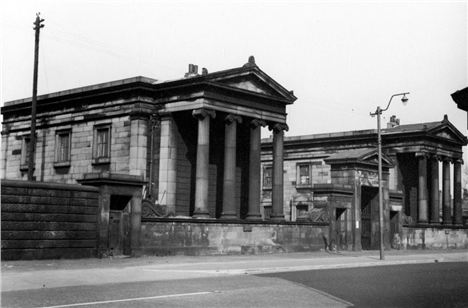

Their mental maps would - it seems - have little or no place for the finest neo-Greek buildings in a city. Old you see. Possibly expensive to save - so let's get rid eh?

"Hey, look at this pile of old crap," somebody must have said in Manchester Town Hall sometime around 1963, "let's demolish these and replace them with a low brick wall."

Sixties blindness - sixties cold rationalism. No place for these suburb and city enhancers

So they did and a befuddled population looked on and did nothing, because no doubt the men from the planning department knew best. So Harpurhey lost its most impressive connection to the past. Manchester's Euston Arch perhaps?

I'm thinking this as I'm approaching Manchester General Cemetery begun in 1837.

I'm thinking I would love to see the fine temples by William Lambie Moffatt in the flesh rather than the photo.

But instead I step over that low wall (has anybody read Ursula Le Guin's Farthest Shore?) to where the dead have been gathered and stored in an up and down landscape to the edge of the sudden deep down of the River Irk valley.

The dead march before us

Amidst the trees and the tall monuments at that far end there is a mini-Manchester Highgate. Here under the broken pillars, the carved hourglasses with the sand all run out, you'll find merchants, industrialists, businessmen and their broods. But you'll also find Sergeant Brett and foundlings.

Brett was the first Manchester policeman to be killed on active duty when he was murdered by Fenians in 1867. His death led to the public hanging of three men of Irish heritage, almost certainly the wrong men, who subsequently became known by the Irish as the Manchester Martyrs. Foundlings were abandoned children, and their sad little graves, paid for by benefactors or public subscription, dot the cemetery.

Over a broken fence to the west there is bumpy terrain. Later I discovered this was where the common graves were located. These graves contain several bodies even hundreds and held the dead who couldn't afford a private grave and also paupers, the literally penniless.

All the time I'd been in the cemetery I'd been the only soul there: the only living soul I should say if I were the type who believed in the blowing of trumpets, the graves opening, the Second Coming and all that. I don't. But the pathos of being surrounded by tens of thousands still has potency and remember, it was planned that almost 200,000 would be buried here, quiet in Harpurhey, waiting for their resurrection.

The hourglass of life is empty but never mind, its sprouted angel wings to carry you to Heaven

As an aside, many of the stones are tumbled flat not through vandalism, but through Health and Safety concerns - although some are now being lifted. You can read about Manchester General Cemetery on this website created by a group of people who clearly have more feeling for local identity than the fools in the planning department in the sixties.

Queen's Park adjoins the cemetery. It was - with Peel Park in Salford and Phillips Park close to the Etihad Stadium - created in 1846, the first of the classic municipal British parks. It is nationally important but doesn't detain people long anymore.

Once famous for its floral displays and its art gallery, Queen's Park is now a low maintenance space, a good place to walk the dog but hardly to linger. The art gallery is a storage and restoration building for Manchester Art Gallery in Mosley Street, barren to the public it was created to serve and more like a factory in landscaped surroundings than a place to escape too.

Across the empty park to the old gallery

There's an irony here that as funding for health care and essential services has risen exponentially, especially in low income areas, such as Harpurhey and Collyhurst, the beauty and pride a well-maintained formal park lent deprived areas has been left out of the equation.

This means the reason for the creation of Queen's Park has somehow been lost, yet the lack of such spaces surely contributes to the low health indices. Why can't a compromise be struck and money somehow diverted into the park? Why must we have one without the other?

Perhaps it's not a council or governance problem. Perhaps we have a philanthropy gap - are there not individuals in Greater Manchester who could help make our parks blossom?

Maybe this could be how the evil of tax avoidance by the big corporations could be handled. Say Google or Vodafone commit to twenty million for Queen's Park then the same figure can be tax deductible.

On leaving Queen's Park I realised it was jammed between Heaven and Hell. Appropriate since it's become a purgatory.

Just outside the southern gate on Queen's Road is the Hellfire Club. A 'goth' spot for vamps and their friends.

I crossed over Queen's Road where there's a good view of the tall buildings in the city centre from the bridge over the River Irk. Then I headed on south through seventies housing that seems well-kept and cared for, over the new Metrolink line, following the road as it dipped into woodland past St Malachy's RC School.

After the junction with Smedley Road and under a viaduct carrying the aforementioned Metrolink there's something to make you smile. You can't help yourself. Why on earth is there a 6.9m (almost 23ft) ship rising out of the ground? (See main picture at the top of the page).

But before answering that question, it's best to continue down the road for a short distance and turn up Fitzgeorge Street under the viaduct and take the path to the left of the United Utilities works. There is an outcrop of purple-red rock here, all that remains of Collyhurst Quarry. This is the stone that built Manchester.

The stone that built Manchester

Chetham's School and Library, St Ann's Church, the orginal Cathedral stonework, Hanging Bridge at Hanging Ditch all came from here. It was so well-known this Collyhurst Sandstone it even became the generic term for this type of north western sandstone.

The official description runs: 'The red stone is about 280 million years old, created from desert sands blown into dunes, when this area of the British Isles occupied low latitude desert belts to the north of the equator. The rock is not very resistant to the ravages of weathering and erosion and disintegrates relatively quickly.'

Look at the interior wall of Chetham's gatehouse and you'll see the truth of this description. When this quarry was exhausted the Victorians turned to the harder golden sandstone you see in the Town Hall. Strangely enough it was Robert Angus Smith in 1852, in Manchester, who first discovered acid rain and its link to carbon burning and industrialisation.

Appropriate this, as by that time much of the acid rain he was studying was being produced in the valley of the River Irk all around this spot.

Oh, and before we leave this chapter it was at the top end of Collyhurst Clough - of which the quarry forms part - where the plague pits of Manchester were located.

But I've had enough of death. It's time for ships, paint, the improbable hill and the impossible bridge.

Fox Courtyard, Chetham's School of Music and Library, from 1421, showing Collyhurst sandstone and industrial 'acid rain' erosion

Chapter Two - Positive Thinking, Paint And Sculptures

Let's start again with that ship launching itself out of the ground.

This is by John Wolfenden for the firm of HMG Paints. It's made from mild steel plates and was erected in 1994.

It’s also a bit of Monty Python, put there by the company as a moment of absurdity to brighten the days of passers-by with its sheer incongruity.

The title of the piece is Dreadnowt/Nothing to worry about and is a Northern play on Dreadnought, the name of the Royal Navy battleship that made every other battleship in the world obsolete when it was launched in 1906. There is no connection to the Irk Valley which makes it all the better.

Sad site-specific artworks that refer to the heritage of an area are two-a-penny in the UK. This is fun.

Pre-WWII industry defined this area, but now there’s only HMG Paints left as a major manufacturer.

In a late nineteenth century survey in our part of the Irk Valley and in Collyhurst, there's a list of the manufacturing taking place. They include an ironworks, several dyeing and finishing plants, paper mills, paint works, brickfields, masonry wrights, saw mills, chemical works including a starch and gum works, machine engineers, a glass works, a plaster of Paris works (presumably not made out of plaster of Paris), a locomotive works, a colliery, a rope works, a naptha distillery and salmo distillery (me, neither), a gas works and a Viagra factory - well I'm assuming that is what a ‘Stiffening Works’ is all about.

No wonder there was acid rain as described in the previous chapter above. Hence all the jobs too and hence the growth of North Manchester.

But that's all gone aside from HMG Paints. So how has it survived?

John Falder, the managing director of HMG paints, talked to me about HMG: "We don't want to leave, we don’t want to sell up. We’ve been here since Harry Marcel Guest set us up on 4 October 1930. We have 170 staff employed with us and we are the largest industrial producer of paints in the country with a thousand active accounts, and this is our home."

“We have survived here - prospered is maybe a better word - because we provide quality products. But more than that it’s because this company is its people. We are bound together with a common purpose almost like a co-operative – but with a board and management.”

Falder on the job - thanks to www.oldclassiccar.co.uk for the picture

I suggest this sounds a little too cuddly for a profit driven enterprise.

“It’s not," says Falder with a laugh, “I mean it. We don’t feel we have to take part in a lot of what now constitutes standard business practice. We don’t have rationalisations that humiliate people by making them re-apply for their jobs. We have stayed put because in terms of our paints we are ahead of the game, but also because we believe we have a duty to those who work with us and have worked for us. Did you know one of the origins of the word ‘company’ is ‘to break bread together’? Well in a paternalistic way, that’s how we see the relationships across HMG.”

So how is this delivered practically?

“We work with the local school academy. We have eight fourteen-year-olds just starting courses with us leading to jobs. We want to be part of Collyhurst, not just people who drive in and drive out because the factory is here. At the same time there are two people in the lab who retired seven years ago and we can't keep them away. They will mentor the young people we have coming in. That's our way of doing things.”

Falder’s words seem like a blueprint to me for British industry. Pride in where you are and what you do, harmonious relations between managers and workers. It's what the Germans deliver so well, long term thinking allied to top products.

You’ll find HMG paints everywhere, on the Brompton bike I was riding down the Irk Valley, on the new 4x4 Jaguar shown below and on hundreds of the household products you use.

Jaguar - the blue is HMG blue manufactured in Collyhurst

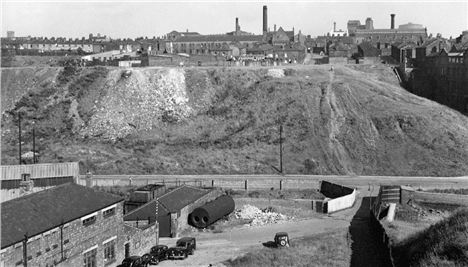

Just after HMG on the right of the valley is The Improbable Hill. This hill looks strange, unnatural. And it is. It’s a spoil hill, steep from the valley, part wooded, part turfed. A hill made from the waste of a 150 years of industrialisation.

Once there was a quarry here, before that there was a pleasure gardens, the toast of Manchester, the playground of the well-to-do. This was Vauxhall Gardens, set up by John Tinker in the 1790s and continuing until the 1850s, when it was swamped by industry. Here there were tea parties, balloon ascents, flower displays, lantern evenings, musical soirees and much else – think Tivoli Gardens, Copenhagen.

When it closed the site was hollowed out as a brickfield and quarry and poisoned in its air and its ground. In the 1990s it was landscaped and raised to this improbable hill, crowned by a sculpture opposite in spirit to Wolfenden’s Dreadnowt.

Andrew McKeown’s Breaking the Mould is ok, inoffensive, but it’s not necessary. There’s no fun in it. Worse it’s off-the-peg art, there are more than twenty of this same work across the country. It's regeneration fodder art.

The industrial mould has broken revealing a seed, a promise of new life for ex-industrial areas. Right. Good. Yawn.

Still of you’re feeling energetic then you can clamber up the highest bit of the sculpture and get a grand view of Manchester city centre. I caught it with the sun low in the sky and the city a heroic silhouette.

Cut out and keep Manchester in silhouette

To the east, nearby, are the unattractive maisonettes and flats of the 1960s Collyhurst slum clearance programme. Those dreaming planners again - see the opening section of Chapter One above.

That slum clearance as can be seen, didn’t quite work out, although the noughties re-working of three tower blocks for private occupiers and capped with the neon names of the Pankhurst family, Emmeline, Sylvia, Christabel – Manchester suffragettes – are sort of fun. At night at least. During the day you wonder why the developer Urban Splash chose the drab, brown walls.

The Metrolink services rattling on the viaducts here rattle over the site of one of Manchester’s worst rail disasters. I have to mention death again. On Saturday 15 August two trains collided and one fell into the River Irk killing ten people.

The tram rattles over the deadly viaduct, the picture is taken from the Improbable Hill

Chapter Three - That Bridge, City Forest And Another Bridge

Back down on Collyhurst Road something was intriguing me. A strange piece of brickwork was rearing out of the trees across the river. It seemed an unfeasibly high lump of dark Staffordshire brick.

I crossed the river and found a path that climbed and turned into a precipitous stair that became the most unlikely footbridge I’ve ever come across. This Impossible Bridge is a vast piece of engineering now lost in a scrub wood of birch and sycamore like something Mayan in a Mexican rainforest.

Up the stairs

Built in the 1890s to lift people from Collyhurst Road to Cheetham Hill, but then also having to lift them again over the now-vanished railway sidings of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, it’s an extraordinary structure. It leads at present from one unimportant nowhere to another unimportant nowhere with ridiculous overbearing presence. Ozymandias eat your heart out.

It’s always impressed as well. It’s even got a place in art history. LS Lowry, the miserablist artist beloved of teatowel makers across the country captured it in a sketch.

The Impossible Bridge provides astonishing views of the city centre and the surroundings, from the moors to the north to the immediate environs.

From the view you can see how the River Irk valley has been reclaimed for nature - aside from the HMG plant and some smaller companies.

Take it back a few years though and this was a burnt, battered, ruined landscape. Curious that while Queen's Park up the way was beautifully -almost London Royal Parks standard - maintained, a half mile away was nothing but a chemically rotten industrial wasteground.

1950s scene showing the view back to the yet to reclaimed Improbable Hill from the Impossible Bridge

Of coruse the perfect solution would have been the environmental cleaning of the valley with retention of scrubbed up industry and the jobs they provided, while, of course, Queen's Park remained manicured.

Not impossible surely? Dream on maybe.

The Impossible Bridge, the Brompton Bike and 'Pankhurst' flats

Under the Impossible Bridge and stretching away on each side are the abandoned railway sidings. Here are acres and acres of brownfield site, an unclaimed nature reserve, a forest a half mile outside Victoria Station, fenced off and hidden in plain sight.

Manchester, it would appear, has a lot of room for manoeuvre in its inner areas. Even the land stretching from Castlefield almost to United's ground between the Ship Canal and the Bridgewater Canal - Pomona - pales in comparison.

The empty acres

Given the forests and woods here before the industrial age, its apt perhaps for them to stage a fight back. The River Irk gets its name from a variant on the word for roe deer. The sentiment seems to have been that it was as fast and nimble as a deer, the fastest in terms of current of the streams and rivers coming into the central Manchester area.

But the notion of deer was fitting too because of the hunting that was to be had here and further up the valley and into Blackley. Not only deer but boar too. Yum. Think of the bird life. Much of it edible. Anybody for woodcock? Whisper it folks but the roe deer are back in those woods beneath the bridge. The Irk has reclaimed its own.

Between the Impossible Bridge and the city centre, right in the foreground of the view there was once Travis Island. This was an area of land made into an isle by a leet that ran a waterwheel that powered a once famous cornmill. The railway sidings did for that little slice of Manchester's baking history.

Back down from the bridge the city closes in. Tatty ex-industrial buildings tighten on Collyhurst Road and the river. At the Dalton Street junction Collyhurst Road becomes Dantzic Street. The name marks Manchester's trading links with Dantzic, now Gdansk in Poland.

Where Roger Street from Cheetham Hill hits Dantzic Street there's a scruffy low bridge over the Irk.

As I took a photograph a head appeared over a concrete wall on the Collyhurst side. Shaved, bald. Tough. The yard he was speaking from seemed some sort of scrapyard.

"You're not going to throw that bike in the river, are you?" the man bellowed about my Brompton.

"What are you saying about my bike?" I laughed.

"Nothing, but they've tried to clean that river and they don't want bikes thrown in it," the man said.

I looked into the Irk, it was choked with discarded waste and plastic bags. I was here to praise Irk, not to damn it. Or even dam it.

"Not sure why for one minute you might think I'd want to throw the bike I've just ridden here into the river," I replied irritated.

We stared at each other across the wall and the road for a tense moment. The man shrugged and disappeared.

I turned to look at the bridge.

Tatty old monument

After Manchester's oldest manmade remains, the Roman wall hidden in a fenced site in Castlefield, this is perhaps the city's most unfortunate listed structure.

Union Bridge, leaping the Irk in a battered single arch, is in a sorry state. When it actually dates from is unclear. The listing says late 18th or early 19th century.

I'm going for the year 1800, the middle way.

It was in that year Britain formally incorporated Ireland into the United Kingdom in a coercive act of Union. Hence Union Bridge I reckon and if so a title full of resonance.

Collyhurst in the next 200 years would absorb thousands of poor Irish migrants. Perhaps given the name Dantzic Street and the numbers of Polish immigrants too, the echoes are even more pleasing.

To be continued - the last section, in which we reach the end of the journey and discus minor issues such as Time with a capital T.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+

IRK VALLEY THE GUIDED WALK: Down the Irk Valley - the Impossible Bridge and the Improbable Hill

Cemeteries, the strangest sculpture in Manchester, great views, astonishing history and a scramble up the stones that built the city (if you feel like scrambling, otherwise you can just take a look from a distance). The tour follows the above story. If you love a two hour walk through epic history and you love sampling the lost corners of Manchester then this tour is for you.It brings together all the romance of faded industry, ruins and memory with dramatic insights into how cities morph and change and new optimism can blossom in even the most unlikely corners of urban areas. We start the tour at Manchester General Cemetery on Rochdale Road, a mile or so north of Victoria Station and easily accessible by public transport, and we finish right in the heart of the city centre.

Tour costs £8 and lasts around two hours. Sensible footwear needed. Meet outside Manchester General Cemetery, Rochdale Road, Harpurhey, M9 at 3pm. Date: Sunday 15 May.

Getting to the start of this walk and travelling around

The most direct way from the city centre is by bus to the cemetery from Shudehill Transport Interchange on the 17 bus. The best way is by tram to Monsall Metrolink station and then via the short walk along Lathbury Street (turn left and first right out of the station). I took a Brompton bike from Brompton Dock at Piccadilly and then caught the tram to Monsall Station. Overall distance from Manchester General Cemetery is around two miles with the diversions and deviations on this route.