Category: Very Good

Here are a few words

‘Who would find eternal treasure, must use no guile in weight or measure’

You what?These are the words around the dome of the Royal Exchange in the trading hall – take a look when you’re in there next. The Royal Exchange was the cotton exchange of Manchester, where on Tuesdays and Fridays members would meet to do business and swap news. The Exchange was expanded and rebuilt on several occasions and attracted manufacturers, merchants, engineers, shippers, bankers and insurers from around the world – often up to 15,000 per day. It was as big as business gets. At its height during the last decades of the nineteenth century up to the Great Depression at the end of the 1920s, it controlled more than 80% of all the world’s trade in finished cotton.

Busy day in the RX eighty something years ago

Busy day in the RX eighty something years ago

How much?

Let me spell it out, more than eighty per cent. And it wasn’t just cotton, let’s remember the role of engineering too. In terms of wealth, influence and power this was the city’s heyday. Go round the back of the theatre pod and you’ll find a photograph of the place in the 1920s packed to the rafters with traders – like the crowd on the terraces in a footy game. Look out for the former trading board close to the ceiling on the west side of the room over the restaurant.

And what was it like?

We're lucky. We have a superb description of a packed day at the Royal Exchange in the 1920s. HV Morton, in the Daily Express, followed a trader as he moved through the crowd.

'As I look down with a feint Olympic feeling from the Strangers’ Gallery I try to follow one little man through his adventures on the floor. I see him moving through the monster, a part of it, yet to me the most important part of it because I am thinking of him as an individual and I watch him stop at various groups, edge his way, say his little bit and move on, watching, searching, trying to make money, and the whole thing so casual, so removed from roll-top desks and all the paraphernalia of the business.

'He stops to make a joke. Someone tells him a joke that makes him laugh just a little bit too much. He is anxious to please. Now he looks grave, and rubs his chin with his little hand and shakes his little head. Did someone try to sell him a pup? Sometimes a man comes to him or rather seems swept up against him in the chaos, and they bring out notebooks and look solemn. They have booked an order. He is, I am sure, having a good day. He is a cheerful little man. I watch him tell the same story time after time in different groups. Often I see him standing politely waiting until a conversation ends before he introduces himself. ’Change is the only place in Manchester where a man will not butt into a conversation, no matter how much he wants to. It is not done.

'And the little man, just as I am beginning to like him, just as I begin to hope that he is kind to his wife and always takes her home presents, when his pencil has been busy on ‘Change, goes and loses himself in the rather grim impersonality of the monster. And the voice of cotton goes on and on and on...’

Who built this one?

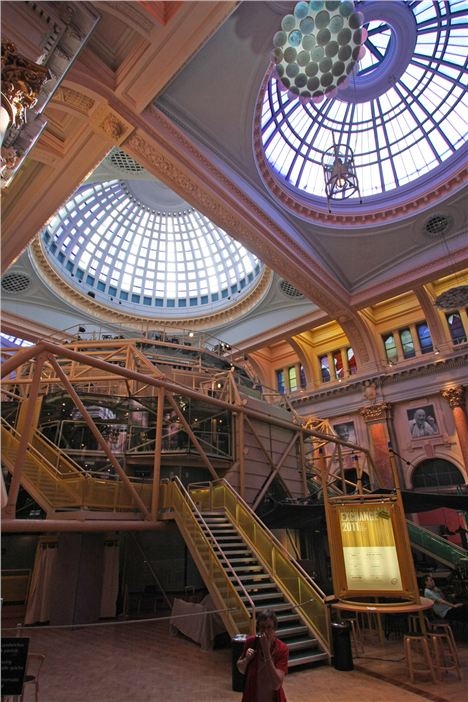

This last Exchange was finished in the 1920s and designed by Bradshaw, Gass and Hope (they also did the old financial Exchange which now houses Stock restaurant on Norfolk Street). It was the last in line of several older and smaller structures stretching back to 1729 – the first of which had even hosted the severed heads of the 1745 Mancunian traitors in the Bonnie Prince Charlie rebellion. This building is a classical structure with pilasters and elaborate detailing on the outside, and that beautiful trading hall inside complete with purple fake marble columns and three domes. It was built as though the cotton industry in Manchester would be permanent…oh the vanity.

Just a minute: fake marbling?

Yes, the effect is called scagliola and is an incredibly skillful way of painting a marble effect. It’s expensive but was needed here because the weight of the real thing would have meant changing the design and practical use of the building under the trading hall. This used to be twice as big, by the way.

The room was bigger than this?

Those Nazis, eh? The Royal Exchange lost its claim to be the biggest trading room in the world when WWII bombing destroyed one half. By the time of the rebuild the telephone had arrived and people didn’t meet as often as they had, so only slightly more than half the trading space was required. The writing was on the wall too.

What do you mean?

The Lancashire cotton trade was dying. Countries with easier access to the raw material and cheaper labour costs were catching up and taking over. Also we hadn’t invested in enough new technology when we should have done. Two hundred and forty-nine years of history came to an end when the doors closed on 31 December 1968.

And then?

And then we were bloody lucky. With remarkable foresight the fledgling Royal Exchange Company commissioned Richard Negri and Levitt Bernstein Associates to build a theatre in the old trading room. The result is that Manchester’s got its own, internal Pompidou Centre (in design terms not function), which was opened in 1976 by Sir Laurence Olivier. In other words, a fiercely individual, high-tech response to the vast chamber which surrounds it, a perfect and total contrast to the older structure, and as sharp today as it was when it opened.

But it was bombed again, wasn’t it?

Oh yes. The IRA destroyed the domes and damaged the theatre in 1996. Two years and £30m later, the building reopened. With some dodgy art: not sure about those glass panels high in the hall by Amber Hiscott, representing textiles in a variety of shades. But at least the hall had been brightened and freshened with the addition of more colour up high and given better facilities – wish they’d lose the huge photos of famous past actors though.

All this seems a bit personal

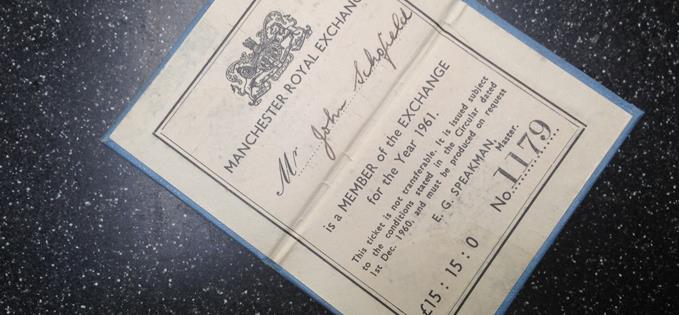

It is. The Schofields used to be members. Because the room got so packed each column in the Exchange was marked on one side with letters and on the other with numbers. Members would meet other members at a position indicated by the intersection of letters and numbers, like a map reference. Thus the textile machinery company of J&H Schofield Limited would meet at J2. But we went bust in the 1950s which was rather too soon for me.