Category: excellent

What do you mean 'city walls’?

Manchester has city walls. City walls longer than most in the country, only here they’re railway viaducts that girdle the city centre for 2.6m (4.2km) from Piccadilly Station clockwise to Victoria Station. Only the distance between Piccadilly and Victoria on the north east side (less than a mile) was unwalled by viaducts. It’s sort of very Manchester too, to have its central boundaries created by industry, trade and peacetime endeavour rather than defence and military need.

Cute idea - but from when do these ‘walls’ date?

The oldest go back to the beginning of the Railway Age. The earliest viaducts from Piccadilly to Castlefield date from the late 1840s when the Manchester, Altrincham and South Junction Railway was built - Manchester's first suburban line.

New Arts Centre site before constuction began with the late 1840s Manchester, Altrincham and South Junction Railway viaduct behind.

Is that the oldest?

Nope. The very oldest set of railway viaducts was erected in 1842/43 through inner Salford for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway by Sir John Hawkshaw, engineer. This line opened in 1844, and connected the Liverpool line with the Leeds line at the present Victoria station. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway created the world’s first passenger rail service in 1830 and previously terminated at the station building now part of MOSI (Museum of Science and Industry). This was an awkward location for most passengers so the decision was made to bring things closer into the core.

But why build viaducts, not just lay the lines on the ground, or in cuttings?

I’d like to say because they look noble as they stride the landscape but that’s not the reason. By the 1840s much of the city was framed by a mixed residential and industrial belt. The only option for the railway companies was to build over these areas as much as they could, sometimes leaving existing structures beneath. By elevating the rail lines less land had to be bought and less work carried out on each side of the lines. Not that this wasn’t still legally fraught. The solicitor employed to negotiate the link line between Castlefield and the line to Victoria Station through Ordsall had so many contracts to draw up he had a nervous breakdown. There’s another curious but far-reaching nugget about these viaducts too.

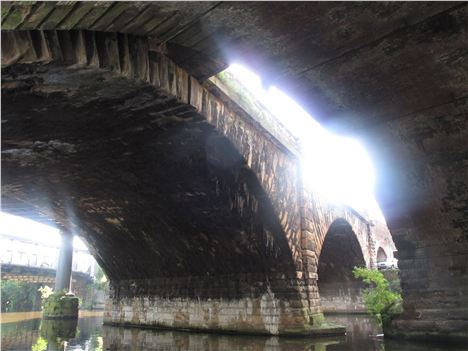

Stuck between later bridges is the Grade 1 listed Liverpool and Manchester Railway viaduct

Enlighten me

Manchester didn’t, to begin with, encourage railways. Despite the industrialised nature of the place - more industrialised than anywhere on the planet - the city fathers didn’t want railways right into the city centre, at least not until 1880 with the opening of Manchester Central station. Think of most other major British cities and the station is right there bang up against the major commercial areas – Birmingham, Edinburgh, Bristol, Glasgow, Newcastle and so forth. If Manchester, the first true railway city, had adopted this idea our main station could well have been along one side of Piccadilly Gardens.

This reaction in the 1830s and 1840s defines Manchester city centre to this day, and placed the major stations and railway companies on the fringe of the commercial core. It’s worth remembering that the early rail systems were controversial with respected people predicting all sorts of disasters and tragedies emanating from speedy steam travel. Nor did the canal companies favour rail travel, and Manchester was riddled with waterways.

Were the viaducts anything other than functional - were they decorated?

Loads of times. Think of the mighty 1880 and 1894 viaducts that cross the Castlefield basin, fashioned from iron and bound for Central Station (now Manchester Central convention complex) and the Great Northern Railway Company’s Goods Warehouse. These huge structures are surmounted by castle turrets to show they pass through the old Roman Fort area of Manchester, even though in that marvellous Victorian doublethink way they completely destroy much of the fort site. Then there are papyrus and lotus leaves.

Massive attack of iron

You’ve gone all botanical?

My absolutely favourite viaduct stretch is that of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway by Sir John Hawkshaw, just to the south west of Salford Central Station. Here he went all Egyptian – or rather Ancient Egyptian. Nicking ideas from antiquity was big in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century - thus Manchester Art Gallery from the 1820s refers to Ancient Greece. But Hawkshaw chose perfectly for a railway viaduct, the temples of Karnak, Memphis and so on are held up by monumental columns. What better than to have these new civil engineering wonders of the industrial age held up by a monumental echo from those times?

And papyrus?

Well the tops of Ancient Egyptian columns (the capitals) were different from Greek ones and used Egyptian local and sacred plants. The red and cream painted columns here are lotus leaf, and the light grey columns have tightly bound bundles of papyrus. It’s all a bit grandly lovely.

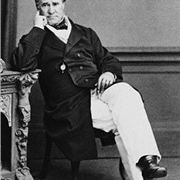

Sir John Hawkshaw - EngineerFinally a word about Sir John Hawkshaw then?

Sir John Hawkshaw - EngineerFinally a word about Sir John Hawkshaw then?

He was born in Leeds and was a true engineering giant. By 21 he was a mining engineer in Venezuela. On return to England he worked with Jesse Hartley designing Liverpool docks, worked on the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal, the Manchester and Leeds Railway, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. In London he was responsible for the Charing Cross and Cannon Street railways, together with the two bridges carrying them over the Thames, and he worked on the Circle Line. He also advised or worked in Germany, Russia, India and elsewhere. He even built the Amsterdam Ship Canal....the list goes on. The Puerto Madero area of Buenas Aires' port is his baby too. Hats off to him. Where did those Victorians get all their energy from? That’s why there’s a problem.

What problem?

The junction between the simple row of papyrus columns doesn’t quite fit up with the lotus leaf columns. The station columns (lotus leaf) seem to have been built first and then the papyrus stretch of viaduct awkwardly matched up with it. Maybe John’s Casio calculator had run out of batteries. Even Victorian civil engineering, it seems, had its failings.

Getting the sums wrong - one column cuts into the other

This story was first published in 2010 and has been re-edited and updated.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+