Manchester School of Art, Manchester

FRIDAY 23 May 2014 was a shocking day for Glasgow, and a shock to the many thousands of people looking at their phones in disbelief. The Glasgow School of Art was on fire. Serious fire. The building for which an entire city is famous, that is acknowledged amongst the finest built in Europe in the last 200 years, had flames roaring through its long library windows, surging between tapered ironwork, lapping the overhanging eaves of its roof. No fire crew ever fought to save a more cherished building. And they knew it. And, despite the total loss of the library, largely, they won.

How can a school building on a back street of a provincial city grow to be so universally loved? A question that may pass through the minds of the judges of the Stirling prize this October, as they pass down Higher Ormond Street towards Manchester School of Art. The Faculty of Art and Design at Manchester Metropolitan University (together with it’s School of Architecture) is now rebranded, and that’s a start.

Night time activity at Manchester School of Art

This is not to say that some higher intelligence might not choose, some time in the future, to rebrand the rebrand, and call the whole damn thing the Ideas Factory, or Planet Create, or some such, but for the present, intelligent retrospective nomenclature prevails and Manchester has a School of Art once more.

And it has a new building, that grows out of a refurbished sixties tower in a scheme by architects Fielden Clegg Bradley (FCB). Those Stirling Prize judges will probably not be stopped dead in their tracks. Of all the buildings on their shortlist, Manchester School of Art is the least architecturally showy. Make no mistake (and you won’t), this is a dressed-down no-nonsense get stuck-in workspace, turned out in neat black overalls. But boring, it is not.

School of Art printed out

The eight-storey tower is especially severe, having lost forty per cent of its glass in the interests of BREEAM and broiling students. Sills have been raised and transoms lowered which means that the bands between floors appear deeper and heavier than they did. This is not especially pleasing, and gives the tower a heavy frown. Don’t be put off. The entrance is in the notch were the new building projects from the tower, which has been cut back to its original core, which is neat, and left of reception.

Above you, and seemingly heading upwards and off in all directions are a fretwork of stairs and bridges which manage to be both heavy and light at the same time. Half, exposed heavy box-form steel painted out in a slimming pale grey. Stair treads, balustrades and platforms half-boxed in in blonde oak. This is classy tailoring for bulky bodies, as impeccably suited to a school of fashion and textiles, as to interior architecture.

Blonde oak up and down

You are off into a workspace, as serious as it is vivacious, concise as it is loquacious. Thanks to two top-lit atria, you climb through light-filled spaces crammed with sewing and knitting machines, Jacquard and Lancashire looms, steam irons, printing-presses, cameras, computers and cutting tables. They call the design space The Shed.

The Higher Education machine that processed me (in the nineteen seventies) is very different from the one at work today. This architecture makes light work, so to speak. It is democratic (though there are staff offices, they are shared, which no doubt drives a lot of senior staff nuts), ecumenical and manufactory. And probably a bit of a mess.

At floor five is a triple height lecture theatre with two collapsible walls, fully retractable doors and pull-out bleachers. Throughout there’s exposed high cement content concrete, and white walls. None of this is mould breaking, all of it is neat, serviceable, and more than a touch inspiring.

Manchester School of Art

There are two protruding light boxes on the fifth floor roof terrace, which itself forms a break-out from the huge lecture theatre. This feels very executive, and has been furnished by the school’s design students. The gathered light is generously sploshed out across the descending floor plates.

There is a flourish; three of the double height concrete columns that rise through the Design Shed are printed on all four sides with an original wallpaper design from 1900 by Lewis Day, who taught in the School of Art. These were achieved in single pours of 7.5 metres, and are a tribute to the quality of the concrete throughout the building.

Concrete cleverness

Pull-down power-points, Belfast sinks, practical spaces, surfaces and services make you want to get on with things. Which is part of the reason one element of the building doesn’t work for me. There is a seven storey vertical gallery that rises through the junction of the buildings. Its commissioners suggest, this to showcase student work. It doesn’t. It is decorative enough, and no doubt it has a fast turn around, but for me, the working spaces, especially in the Design Shed, are the energy and the exhibition. And boy, what an exhibition.

Everyman Theatre, Liverpool

And the Stirling Prize judges move on to Liverpool. If you haven’t been along to Hope Street for half a dozen years, you might not notice there’s a new building here. The new Everyman Theatre (that opened less than a year ago) stands almost exactly where its celebrated and much-loved predecessor sat. And, at first glance, it appears to take up much the same position. Long’ish, low-lying, falling in step with the measured stride of one of the most elegant streets in Europe; why ever would you not?

Liverpool Everyman

Before you go inside, turn back and climb the steps of the Catholic Cathedral. Turn around and look back at Everyman. Now you will see it takes two steps up from the street-line roof towards four big ventilation funnels. (You would be foolish not to step inside the Cathedral whilst you’re here, to remind yourself of its undervalued splendour).

The all new Everyman is a card-trick of eight interleaved half-floors slotting around the auditorium that is almost exactly where it always was and is built largely from the same bricks, which had already been recycled from nineteenth century Hope Hall that stood on the site.

Let me be clear; this is a difficult building to describe, not because it is complicated or tricky, but because it is thoughtful and clever. When I say that spaces are vertically visually interconnected (as in Manchester School of Art), here, you might have to open a dock-door in the wall of a meeting room, suspended above the main entrance, or you might neatly fold back a shutter on the landing leading to the Writers’ Room. Or you might look down the light-well from the admin offices.

Liverpool Everyman interior

At pavement level, most of the ground-floor full-height glass opens on to the street. This is café, box-office foyer and stair-wells up and down. You can identify the enclosing walls of the auditorium in their dressed brick. The ceiling is a fresco painting by Antoni Malinowski, and is as subtle as the building it adorns.

First floor is a more generous height, running the full length of the building. Here, high cement content concrete, visible throughout the building, is matched with engineered sawn oak floor, discreet drop lighting and pleasing retro furniture, and a bar that comes mainly into use at night. All the windows in this area swing open onto a narrow, though load-bearing terrace, which sits behind the cut-metal vertical louvres, of which, more latter.

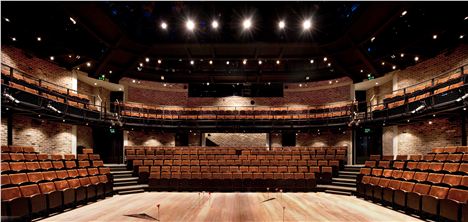

The auditorium is generous not large. Four hundred seats in its (most frequent) thrust stage configuration. Plush seating is deceptively retro as in the rest of the public spaces. Under seat ventilation, fully accessible lighting rig, massive dock-doors and well sighted control gallery must surely make audiences, performers and techies purr with delight.

Liverpool Everyman auditorium

Everyman Youth Theatre was always the energy and edge to this place. It now has its own space at the top of the building, as big as the auditorium itself. On a wall at the entrance to the admin offices halfway up the building is a blow-up of the legendry 1974 Everyman Company, put together by Alan Dosser and Jonathan Pryce (who took the photograph).

Julie Walters, Bill Nighy, Matthew Kelly and Nicholas Le Provost, all look down on to the new foyer of the building that was their mutual foundation. Sensibly, whilst you can, if you know where to look, glimpse their presence, they are not invited to dominate the all-new show. Perhaps Liverpool Everyman learns the lesson of the cool hand of too much nostalgia.

I receive an email from Steve Tompkins of Howarth Tompkins, architects of the new Liverpool Everyman. He’s answering a question I have: “Yes the handles are knurled bronze, to our design.” They dress the main doors and all doors into the auditorium. And they are tall, slim and rather beautiful. And they are neatly matched by the bronze noses on the treads of the main staircases.

The Everyman Bistro was as important to this building’s predecessor as the theatre itself. It was independently run, and kept its own hours. And it was the soul of defiant Liverpool in the dreadful eighties and through the nineties. You knew you were in the right place when all four McGann brothers, their sister, and mates were gathered round tables in the big room. So cherished was the Bistro, the new building has predictably failed to match it.

Liverpool Everyman Theatre Bar

Though the new basement Bistro space is as classy and well thought out as the rest of this building, it has not found its lovers yet. The space itself has turned through ninety degrees, so even though the entrance is in the same dimension, the new Bistro runs in a different direction. Give it time, something big needs to happen here, and it will take off.

When the Stirling Prize judges have done their tour, and step back on to Hope Street, they might cross over to the other pavement and look again at the carefully redesigned Everyman red neon by artist Jake Tilson, and the new façade. This is 105 water-cut metal sunshades, each of which is a life-size portrait by photographer Dan Kenyon of Liverpool people; of Everyman. I wasn’t sure how effective this huge work is when I first entered the building. By the time I came out, I couldn’t take my eyes off it.

And finally…

Will either of these buildings win the Stirling Prize? I don’t think so. In a weird way, the premiere prize for British architecture isn’t set up for a building so gloriously practical as FCB’s Manchester School of Art. Might Everyman pip The Shard or The Olympic Aquatics Centre? It would if I were to judge.

Who will win? I’m not telling you. But I will say that were I to enrol at Manchester School of Art this September I’m sure I would be uplifted by the building I work in. And were I to take the ovation from an audience at The Liverpool Everyman Theatre anytime, I should gladly share it with architects Howarth Tompkins. If there is a better modern theatre building in Britain, I haven’t seen it.

Thanks to Philip Vile for the Liverpool Everyman photos.

![Liverpool_Everyman_Exterior_Night_%28C%29_Philip_Vile[1] Liverpool_Everyman_Exterior_Night_%28C%29_Philip_Vile[1]](https://assets.confidentials.com/uploads/imported/i/O6A/7JQI_K.jpg)