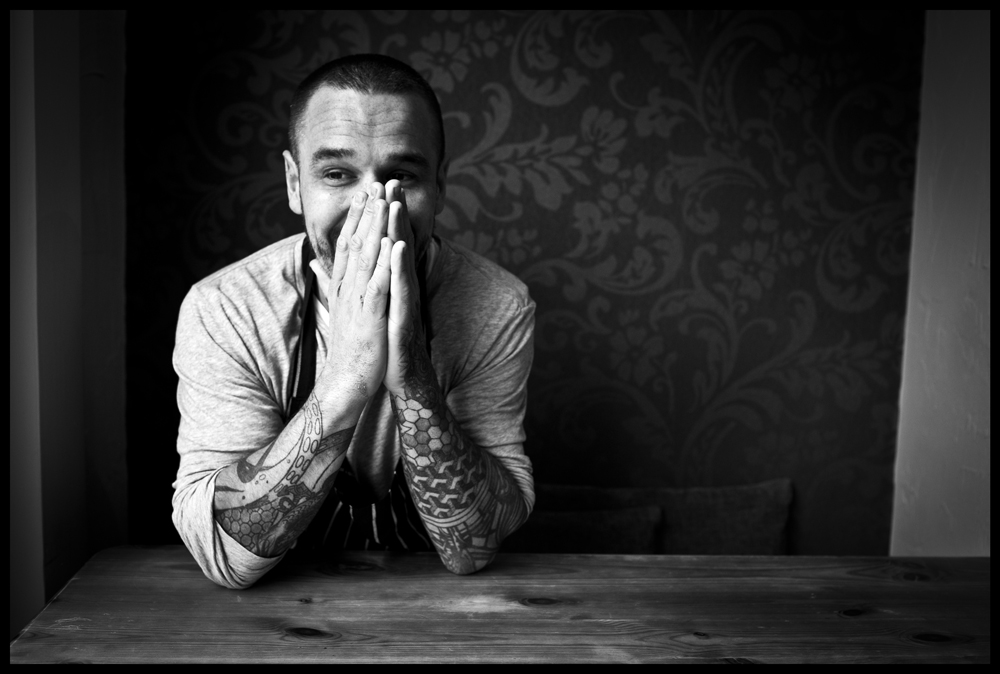

THAT Laurence Stephen Lowry is a lazy sod he’s been sat at the bar of Sam’s Chop House for four years now. And do you know what, he's never bought a round for anyone.

Understood correctly, Lowry’s vision is anything but a hankering for the good old days, instead it’s a documentary distorted (often cruelly) by the artist’s individual viewpoint.

I’ve frequently been rude about Lowry.

Growing up in Rochdale as the popularity of the miserablist artist soared I found I couldn’t abide the man or his art.

Maybe it was because he was so commonplace, every pub in the area had some badly reproduced print of lots of little people rushing aimlessly about under leaden skies amidst overbearing mills. The palette was drab in the extreme, mucky white, grey-black and brick dust red.

The 1977 song ‘Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs’ (click here) with its 'life were grand when we had nowt' mood, did nothing to make me think more of the man.

I wanted my North West of England to be modern, exciting and sophisticated. I wanted to be an individual not de-individualised like one of the people in his matchstalk pictures. As an insufferable culturally aware (or so I thought) lad I found Lowry's art too bleeding obvious, too damned parochial.

The endless media coverage in the years after Lowry’s death in 1976 confirmed it all. There he would be in his 1950s’ overcoat, out-of-time trilby and tatty looking shirt and tie posed on some grim terraced street. It made me shudder.

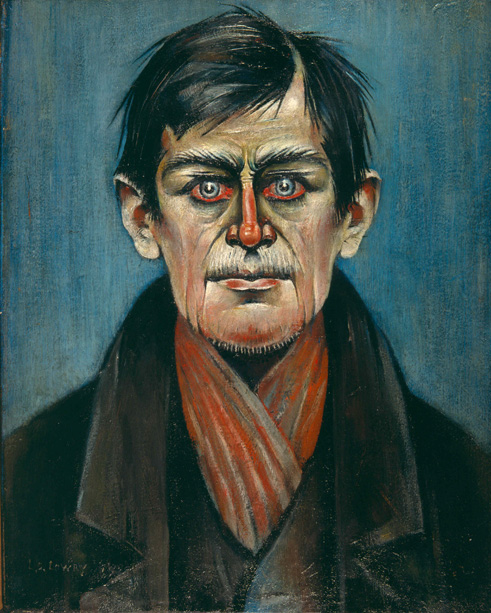

Now I’m the same age as Lowry when he painted ‘Head of a Man (Red Eyes)’ in 1938. I’m 51, just as he was, and I really hope I never see the terrifying bleakness Lowry saw when he looked in the mirror that year.

Head of a Man (Red Eyes)

Head of a Man (Red Eyes)So in 2015, shorn of the pure, hard certainties of youth, I can now re-evaluate Lowry. I can see the depths hidden under his ‘Where’s Wally’ industrial pictures. I can appreciate his eerie portraits, his empty landscapes, his haunting seascapes revealing the loneliness of an individual rigidly corseted by his nature and nurture. I realise I was being simplistic in finding him simplistic.

Seascape

SeascapeLowry was born in Old Trafford in 1887 and lived in Greater Manchester in various homes all his life. He was massively introverted, never had an adult sexual relationship, was a teetotal, non-smoker and funded his painting by rent-collecting. His early life was submerged by a strong mother who ridiculed his attempts at being an artist, until of course he started to gain success at which point she popped her clogs.

That was in 1939. Firmly middle-class, his mother Elizabeth had been frequently ill and when forced to move from leafy Victoria Park to the hard-edged mill-town of Swinton by the debts of her husband and Lowry’s dad, Robert, her irritability increased. After Robert’s death in 1932, she had been bedridden, cared for by her shy, bachelor son. Shudder-time again.

Lowry's paintings and sketches are shot-through with the choking claustrophobia of that Norman Bates-like existence.

A lonely stack of rock thrusting out of grey sea is called ‘Self-portrait’. People in the pictures are seldom touching, atomised, dominated by the inaminate objects around. Those tall isolated mill chimneys stand just as tall and isolated as Laurence Stephen Lowry did, alone amidst the urban hubbub.

“Forget sentimentality,” says Michael Simpson, director of the Lowry's galleries. “Lowry hated sentiment, he always said the works he produced came from what he saw.”

He’s right. Understood correctly, Lowry’s vision is anything but a hankering for the good old days, instead it’s a documentary distorted (often cruelly) by the artist’s individual viewpoint. Art is, obviously, not just about sweetness and light but I like to feel some sense of community with the rest of mankind through art. You don't with our Laurence. Despite his persistence of tenure at the bar of Sam's Chop House, he's the regular who prefers to drink on his own.

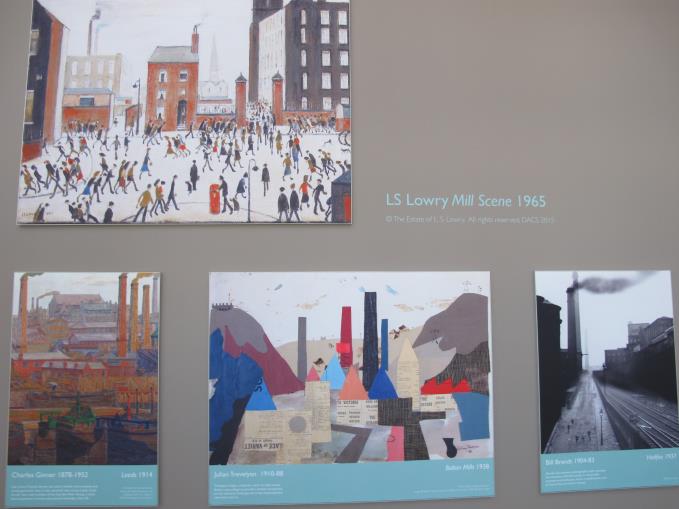

Claire Stewart, the curator of Salford's Lowry archive and artworks, and Simpson, have also worked hard to place Lowry in the context of twentieth century art history and their thoughtful displays comparing Lowry to his contemporaries and describing the physical environment in which he lived are very good. Lowry is shown, in print, next to other more internationally recognised artists such as George Grosz, Edward Burra and Paul Nash to try and prove that he isn't so different.

This doesn't convince.

After the Tate Gallery show in London two years ago and its hundreds of thousands of visitors, Lowry's standing is rising, but if he were to slot into the story of 20th century art then it would be as a cul-de-sac, a dead-end, interesting, occasionally fascinating, but leading nowhere except back in upon himself.

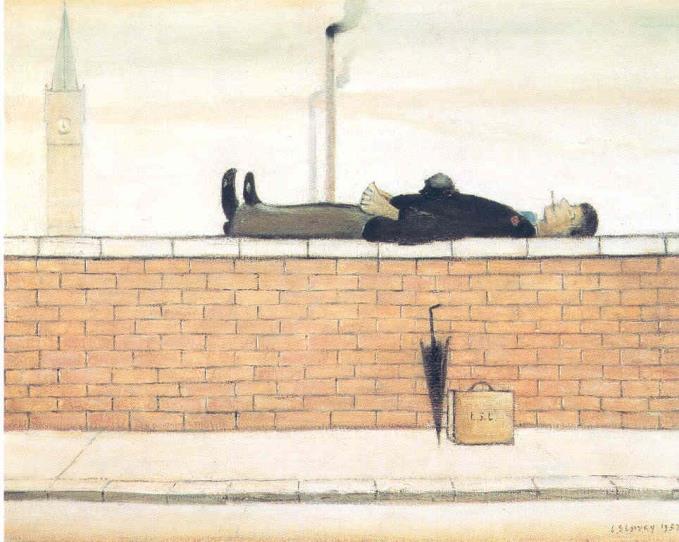

Still, this is the best exhibition about Lowry we've had in the North West - to my mind. Aside from those portraits and seascapes ("Lowry should be considered one of the great painters of the sea," says Simpson) there are lots of crowd-pleasers too, 'Going to the Match', 'Coming from the Mill', 'Man lying on a Wall'. There's much to enjoy and you'll find there's a deeper Lowry to discover. If those depths seem to underline a life lived in scary seclusion, without much in the way of warmth or society, then don't let that put you off.

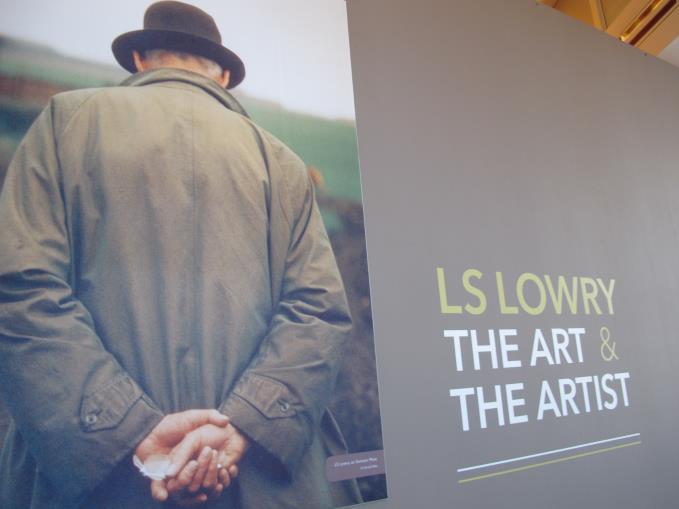

Aptly, the opening image of the exhibition is a picture of Lowry with his back to the viewer. The enigmatic image seems about right. The art establishment and people like me have turned our backs on Lowry for many years. He returned the favour and didn't give a damn what we thought. It's perverse and amusing that as his reward he's become one of the most popular and recognisable - in Britain - of all British artists. You should see the amount of merchandise available in the shop on the floor beneath this exhibition.

LS Lowry: The Art & Artist opens Saturday 13 June, The Lowry, Pier 8, Quays, M50 3AZ. 0161 876 2024.

Jonathan Schofield took part in the Lowry Experience package. This includes a room for two in the Lowry Hotel, breakfast, and a two hour taxi tour for two people around Lowry’s Manchester with qualified Green Badge Guide John Consterdine.

Man lying on a wall

Man lying on a wall The Lowry and some contemporary 'matchstalk' people

The Lowry and some contemporary 'matchstalk' people