ZERMATT’S all about anniversaries. 2015 marks the 150th of the first conquest of the Matterhorn, the iconic peak that defines the Swiss mountain hamlet, while this year it is four decades since I first visited on my virgin trip abroad as a schoolboy.

‘Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are naught without prudence, and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste, look well to each step, and from the beginning think what may be the end’– Edward Whymper’

Of course, I’m just an infinitesimal footnote in the history of the resort, while the ill-fated expedition led my controversial fellow countryman, Edward Whymper, has resonated down the decades, bedevilled by tangled claims and counterclaims. The rope snapped on the way down. Discuss.

Zermatt is making much of the commemoration next year. As it should. The exploits of Whymper and his fellow mountaineers were the catalyst for the tourist trade that transformed a remote, peasant enclave into the definitive all-year round Alpine destination.

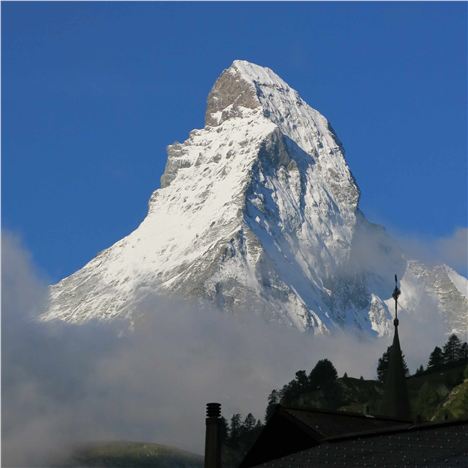

There may be more swank and bling around Verbier and St Moritz, but Zermatt is a class apart. There are no paparazzi to the hound the rich and famous who hide away here; there is a range of affordable accommodation, too, adding to the democratic feel. The welcome is accentuated by the townscape, where traditional low-rise wooden architecture has not given way to the ski lodge concrete excrescences you find elsewhere. Stepping off the train up from Visp in the the valley, it felt much as it did all those hazy decades ago. Even though I’d arrived late and the charismatic pyramid of the Matterhorn was cowled in darkness. Perhaps there were more horse-drawn carriages about in the old days. Certainly there weren’t the electric taxes and mini-buses that now ferry folk and bags around in a resort that bans cars.

There may be more swank and bling around Verbier and St Moritz, but Zermatt is a class apart. There are no paparazzi to the hound the rich and famous who hide away here; there is a range of affordable accommodation, too, adding to the democratic feel. The welcome is accentuated by the townscape, where traditional low-rise wooden architecture has not given way to the ski lodge concrete excrescences you find elsewhere. Stepping off the train up from Visp in the the valley, it felt much as it did all those hazy decades ago. Even though I’d arrived late and the charismatic pyramid of the Matterhorn was cowled in darkness. Perhaps there were more horse-drawn carriages about in the old days. Certainly there weren’t the electric taxes and mini-buses that now ferry folk and bags around in a resort that bans cars.

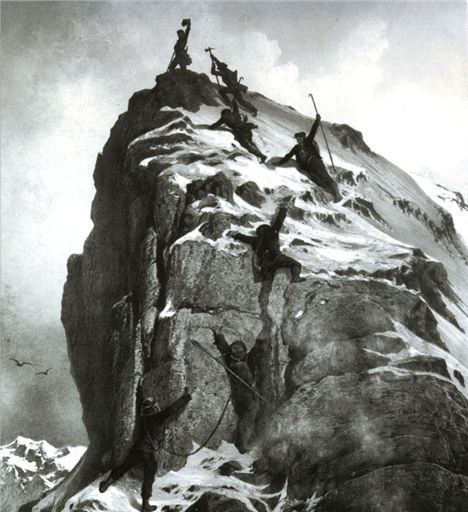

Edward WhymperOf course, Zermatt was far different, primitive almost, during the time of Edward Whymper, an alpinist so obsessive that when in his sixties, grounded in suburban Teddington, he married a girl 40 years his junior he gave her as a wedding present an ice-axe. You feel he was only in his element tackling the 38 four-thousand metre plus peaks around Zermatt. He was not alone. One by one they fell to climbing teams (mainly British, accompanied by local guides) until the Matterhorn alone was left. At 4,477m, not the highest, but mythical, sinister, deadly, the ultimate challenge.

Edward WhymperOf course, Zermatt was far different, primitive almost, during the time of Edward Whymper, an alpinist so obsessive that when in his sixties, grounded in suburban Teddington, he married a girl 40 years his junior he gave her as a wedding present an ice-axe. You feel he was only in his element tackling the 38 four-thousand metre plus peaks around Zermatt. He was not alone. One by one they fell to climbing teams (mainly British, accompanied by local guides) until the Matterhorn alone was left. At 4,477m, not the highest, but mythical, sinister, deadly, the ultimate challenge.

Whymper had travelled to join an Italian team attempting the ascent from their side, but they set off before he arrived. Undaunted, he swiftly assembled his own team out of Zermatt and they reached the top on July 14 with the Italians only minutes away below them. Pelted with stones by the triumphalist Brits, they turned back. “We remained on the summit for one hour – one crowded hour of glorious life,’’ wrote Whymper.

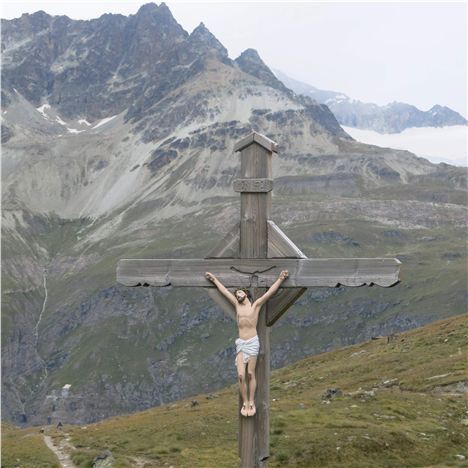

Calvary above Zermatt; so many have died in these mountains

Calvary above Zermatt; so many have died in these mountains

The aftermath was less glorious. On their way back down, the most inexperienced member of the roped-together crew, Douglas Haddow slipped, dragging three companions with him 4,000ft to their deaths on the glacier below. Only a thin rope that snapped saved Whymper and experienced Zermatt guides Old Peter Taugwalder and his son, Young Peter. Ever since there have been accusations of the rope being deliberately cut, of a cover-up to preserve the reputation of Zermatt. We’ll never know the truth. It certainly left Whymper, then only 25, a haunted man for the rest of his mountaineering life.

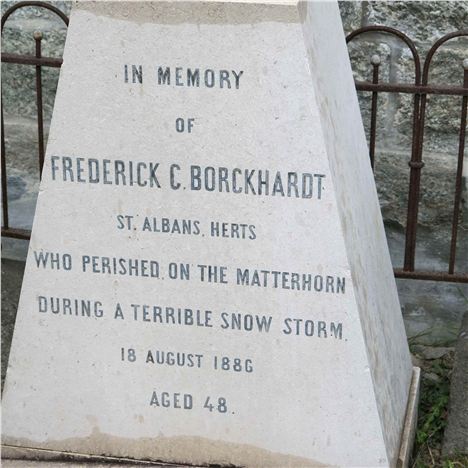

Grave in The English Churchyard; below, a memorial to an 1865 victim

Grave in The English Churchyard; below, a memorial to an 1865 victim

After the tragedy Queen Victoria tried to stop her subjects tackling the Alps but the lure was irresistible. To this day the Matterhorn alone has claimed 450 lives. A good few are buried in the little English Church in Zermatt. Two of the English climbers who died on the descent were laid to rest there: Haddow is buried outside, while the Reverend Charles Hudson lies by the church altar. The body of the third English climber who lost his life, Lord Francis Douglas, has never been found.

The Taugwalders’ tombstone is in the Mountaineers’ Cemetery by the Catholic church in the village church, not far from their family home with its plaque. It’s an atmospheric place to start a tour of the town. The Hotel Mont Cervin Palace has its own shrine of alpinist memorabilia, but I’d recommend Zermatlantis, an interactive subterranean museum under a glass dome near the village church.

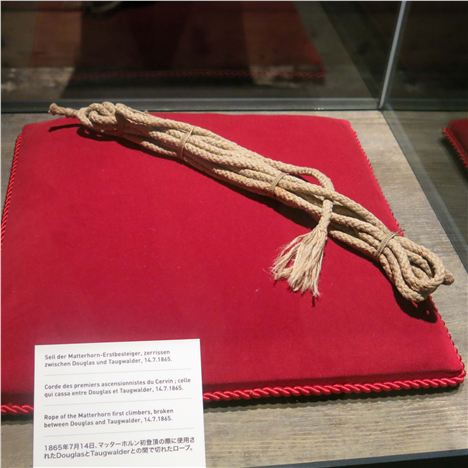

Rope from the triumphant but tragic 1865 Expedition

Rope from the triumphant but tragic 1865 Expedition

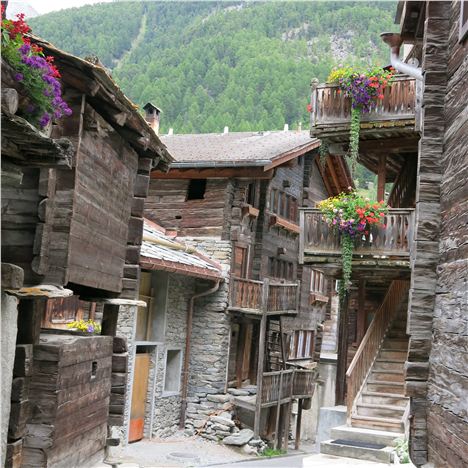

The Hinterdorf is the oldest part of Zermatt

The Hinterdorf is the oldest part of Zermatt

Besides tracing Zermatt’s history before and after it became a resort, it showcases the notorious frayed rope from the 1865 expedition. I’m always sceptical about the provenance of Saints’ relics and the like but along with other relics of those early climbing days this is genuinely poignant. The older quarters of the town are nearby. A ramble around the Hinterdorf and the Englischer Viertel (English Quarter) is delightful, recalling the rustic, peasant past just yards from the main drag, Bahnhofstrasse, flaunting its Swiss watch emporia and designer outdoor gear.

The Matterhorn Express whisks visitors up to the Schwarzsee and beyond

The Matterhorn Express whisks visitors up to the Schwarzsee and beyond

Enough town, the Matterhorn calls. There are amazing views around every corner, provided the clouds are kind, and the whole area is a walkers’ paradise, but most of us need a leg up to get to altitude, where you can get a close-up of the iconic peak. That’s where the terrific array of funiculars, gondolas (cable cars) and ski lifts comes in. Passes giving access for any number of days are available.

My first ascent was to the Matterhorn Glacier Paradise 40 minutes away. Europe’s highest altitude aerial cableway whisks you directly up to 3,883 metres above sea level and a viewing platform that takes in the peaks of the Monte Rosa Massif and the disorienting south side of the Matterhorn. It takes your breath away. Literally. My head was spinning as a spot of altitude sickness kicked in. No way was I heading along one of the ridge paths or taking advantage of the 365 days of skiing up here.

Photo opportunity inside the Glacier Palace

Photo opportunity inside the Glacier Palace

I was happy to head underground. The Glacier Palace tunnels burrow 15 metres below the surface of the glacier the highest of their kind in the world with ice sculptures and real crevasses. Oh, and on show in a case in this natural cellar a Johannisburg wine from Europe’s highest vineyard (rising to 1,150m above sea level), run by the Visperterminen co-operative. The Valais here is Switzerland’s largest wine producing area and the whites especially are quietly impressive, the beer less so.

On the way back down from the Glacier Palace, it’s worth stopping off at the Schwarzsee (Black Lake) with its chapel and footpaths that take you as close to the Matterhorn as a sensible pedestrian might want to get.

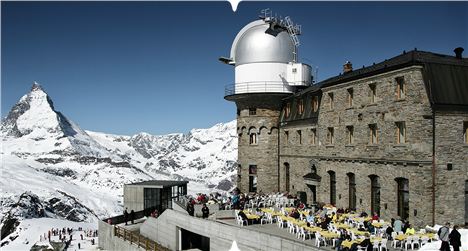

The sun terrace of the amazingly situated Kulmhotel

The sun terrace of the amazingly situated Kulmhotel

Less devastatingly ice-bound in high summer is the Gornergrat. This is reached via Europe’s highest open air cogwheel railway (www.gornergratbahn.ch). The trip takes half an hour. At the terminus is the Kulmhotel, highest hotel in the Swiss Alps at 3,089m, with its own observatory. As well as the stars and beautiful sunsets, from here you can view 29 mountain tops above 4,000m, including the highest Swiss peak, the Dufourspitze, at 4,634m, and gaze across at the second-largest glacier in the Alps, the Gorner glacier.

The Glacier cuts an icy swaithe through the Alpine landscape

The Glacier cuts an icy swaithe through the Alpine landscape

The Kulm is the starting point for the Gornergarat Gourmet Ticket

a downhill day walk witj meals en route. Breakfast is here, followed by a starter, salad and main at the Riffelberg Hotel, 500m lower. It’s one of the oldest in the Alps, built in 1853 on the initiative of the local priest to capitalise on the burgeoning tourist market. It was a location for Ken Russell’s film Women In Love (who can forget the nude wrestling scene between Oliver Reed and Alan Bates?).

Riffelberg chef Christophe Niermeyer; below his lamb and polenta dish

Riffelberg chef Christophe Niermeyer; below his lamb and polenta dish

The original dining room is lovely, as was the white wine soup and mountain lamb we were served. We asked chef Christophe if it came from the picturesque herds of black-nose sheep we had photographed on the way down. “Not them, they are kept out there to pose for the tourists.’’ he replied.

The rustic Chez Freddy lodge further down on the Riffelap provided dessert – perhaps the best apple strudel I’ve ever tasted. I walked off the calories during the next hour and a half’s trek down through the forests to Zermatt past the Gornerschlucht, a precipitous river gorge slashed into the rock.

In summer 2015, amid all the anniversary commemorations, that same Riffelberg will host an open-air theatre, giving 35 performances with 40 actors, in a variety of languages, of The Matterhorn Story, a specially commissioned play, which leans towards the conspiracy story that the rope was deliberately cut in 1865. A case of dramatic licence, but it’s obvious 150 years on, the tragic Matterhorn story will never be laid to rest.

Blowing their alpienhorns at the hotel reached by the new Sunnegga Funicular

Blowing their alpienhorns at the hotel reached by the new Sunnegga Funicular

Fact file

Zermatt, like Switzerland as a whole, is not the most affordable country in Europe to visit, but it is possible to seek out bargains in accommodation and places to eat. Neil Sowerby stayed in Zermatt at the family-run Aristella Swissflair Hotel and Apartments, Steinmattweg 7, 3920 Zermatt, Switzerland. +41 27 967 20 41.

Zermatt, like Switzerland as a whole, is not the most affordable country in Europe to visit, but it is possible to seek out bargains in accommodation and places to eat. Neil Sowerby stayed in Zermatt at the family-run Aristella Swissflair Hotel and Apartments, Steinmattweg 7, 3920 Zermatt, Switzerland. +41 27 967 20 41.

Recommended place to eat in Zermatt, the Cafe du Pont. Despite the title, Germanic staples dominates – bratwurst, rösti potatoes, salad and a large wheat beer for under 20 Swiss francs and excellent fondues.

Switzerland Tourism

For more information on Switzerland visit www.MySwitzerland.com or call the Switzerland Travel Centre on the International freephone 00800 100 200 30 or e-mail, for information info.uk@myswitzerland.com; for packages, trains and air tickets sales@stc.co.uk.

Swiss International Airlines

UK to Zurich:

SWISS offers up to 19 daily flights from London Heathrow, London City, Birmingham and Manchester to Zurich. Fares start from £147* return, including all airport taxes, one piece hold luggage and free ski carriage. For reservations call 0845 6010956 or visit: www.swiss.com.

*A leading fare and is subject to change, availability and may not be available on all flights. Terms and conditions apply.

The Swiss Travel System provides a dedicated range of travel passes and tickets exclusively for visitors from abroad. The Swiss Transfer Ticket covers a round-trip between the airport/Swiss border and your destination. Prices are £96 in second class and £153 in first class.

The Swiss Travel System provides a dedicated range of travel passes and tickets exclusively for visitors from abroad. The Swiss Transfer Ticket covers a round-trip between the airport/Swiss border and your destination. Prices are £96 in second class and £153 in first class.

For the ultimate Swiss rail specialist call Switzerland Travel Centre on 00800 100 200 30 or visit www.swisstravelsystem.co.uk.

The Swiss Pass offers you unlimited access on the network of Swiss Travel System, by boat, bus and train. The Swiss Pass is sold for 4, 8, 15 or 22 days or one month and allows a free entrance to over 400 museums and exhibitions.