THIS is part one of an occasional look at some of the buildings and structures around the city that we pass without a second look.

We'll be venturing further afield across the city region and also focussing on particular times in the city's history. So expect columns on lesser known buildings in south Manchester, north Manchester and other areas plus features on, for example, cracking Modernist buildings from the sixties which we mostly ignore but deserve a moment's pause.

Brook’s Bank - Brown Street

This is the sweetest of banks. It was built as the 1868 headquarters of Sir William Cunliffe Brook’s eponymous bank. George Truefitt designed it in the Gothic style and worked in the initials of the owner and the date over one of the most elaborate and evocative entrances in the city. Under the canopy of the corner bay is a field of stone flowers carved with freedom and ease by Williams and Mooney. The iron corona on the top was by the top Manchester iron foundry of Bellhouse who had earlier in the century built the terminus of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

The building we see today is a small part of a much larger whole that extended to King Street. Now it’s part of Burger and Lobster. William Cunliffe Brooks, barrister, MP, philanthropist, banker, famously preferred water to alcohol or tea, so in honour of him keep it simple and just go in for a meal.

Delight in the detail

Delight in the detail

Heywood’s Bank - St Ann’s Street

Staying with banks this is everything the energetic Brook’s Bank isn’t. This is a measured, calm piece of work that is a classic of its kind in the elegant Renaissance mould. Now the Royal Bank of Scotland, the building first opened as Heywood’s Bank in 1848 on the site of the former family home and an earlier bank. It was designed by the excellent John Gregan and was his finest work. The Heywoods were one of Manchester’s greatest philanthropic families and amongst other things the prime instigator of the Mechanics Institute. The latter was designed to give a leg-up to skilled working class men, Gregan would design a building for them that also still survives on Princess Street in 1856.

This building is all about harmony and clarity with Gregan being careful to choose stone that was resistant to erosion and that could be carved. The rustication, the incised stonework particularly on the lower floor, plus the beautiful window surrounds shows remarkable balance and skill. The building makes up two parts with at a lower scale the attached red brick, former bank manager’s house. The whole is a classic Manchester ‘palazzo’, a building based on Italian Renaissance palaces.

Harmony in stone

Harmony in stone

Law Library - Kennedy Street

Thomas Hartas’ former Law Library from 1885 is one of the very best Victorian buildings in Manchester in terms of fitting in with the streetscape. It doesn’t overwhelm the street yet is as florid and ornate in its Venetian Gothic styling as a fancy jewellery box. In its category of size it's perhaps the best little Victorian building in the city centre, along with Mynshull’s House, see below.

There’s oddness about this building too. It’s Hartas's only monument. he’s not mentioned with regard to any other building, he doesn’t appear in the records at all, he's Mr Nowhere Man. That this is a one-off given the talent on display is peculiar. Maybe he got fed up with designing after this one building. Maybe all the architectural records have got the name wrong. Still if it was Mr Thomas Hartas who gave us the Law Library then he picked a damn fine way to start and a damn fine way to end. Meanwhile we can enjoy the gorgeous deeply set windows with their fancy tracery and the noble typeface of the title of the building.

Great windows great typeface

Great windows great typeface

Mynshull's House - Cateaton Street

Dated 1890, this red sandstone with tile building on Cateaton Street marks an earlier building which was home to Thomas Mynshull. The latter was an apothecary who worked and died here in 1689 leaving money for the apprenticeship of ‘poor, sound and healthy boys of Manchester in honest labour and employment’.

Ball and Elce who designed this building seemed to have a fun time, adding carvings here and there as they deemed fit. The carving was the work of John Jarvis Millson who also designed the sculptural work on London Road Fire Station. The gable at the roofline adds a further jolly note and the building makes one half of an entertaining pair if taken with the ludicrously thin Britannic Buildings, now host to Hanging Ditch Wine Merchants. The latter is one room thick but finds space for a timber turret at the top

Mynshull's and the skinny neighbour

Mynshull's and the skinny neighbour

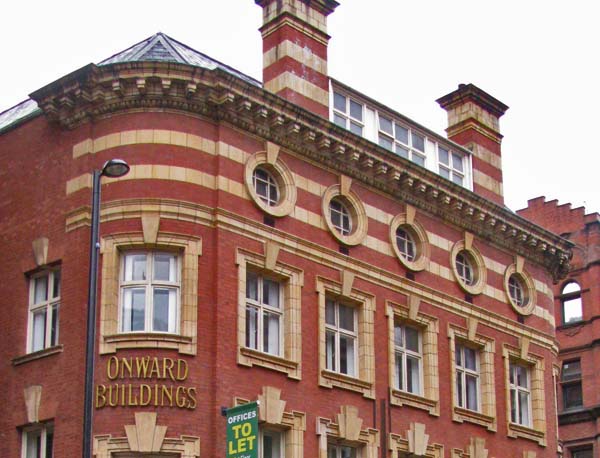

Onward House - Deansgate

Charles Heathcote, the designer of Onward House, is everywhere across the city centre. He designed Parr's Bank, now Brown's Restaurant, The Lancashire and Yorkshire Bank, now Rosso Restaurant, both on Spring Gardens, and the old Lloyd's Bank on Cross Street. In Piccadilly he designed the textile warehouse presently hosting Abode Hotel. For twenty years in Manchester he was the man if you wanted an office. He even designed the building opposite Onward Buildings, Royal London House, at the junction of Deansgate and Quay Street. Onward is a little different though. It was a charity building and is almost delicate in comparison. It exudes charm, flirting with Deansgate, with playful bands of red brick, yellow sandstone and yellow terracotta. Tapeo and Topkapi restaurants occupy commercial units on the ground floor, then there’s three storeys with the windows framed by bold surrounds, the top floor has round windows jazzily linked by yellow bands, all pulled together by a massive but balanced cornice. Then there's the pair of tall elegant chimneys capped to match the cornice and framing attic windows. It's a delight how the building turns the corners with a cool curve at each end of the facade. The first floor balcony over the grand doorway is crowned by its cherub under a shield. The typeface on the shield melds Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau and reads of Band of Hope, a children’s charity that still exists. Inside, closed to the public, the top floor is a wonderland of green tiles.

Onward Buildings (credit: Manchester History)

Onward Buildings (credit: Manchester History)

Sacred Trinity Church - Chapel Street

The oft-overlooked old church of central Manchester and Salford, unlike the Cathedral and St Ann’s, started life in 1634-35. The tower is original, the rest of the church was rebuilt in 1752-3. The architects of Sacred Trinity are unknown. The stone used is that handsome purple pink – almost bruised – local sandstone. The money back in the 1600s was given by Humphrey Booth, a textile manufacturer who had a mansion across the road close to the river. He fought long and hard to get Salford its own church, rather than people having to walk over the bridge to Manchester. The Booth family were one of the most charitable in Manchester’s history and their charities still exist today. Two of the family also became Archbishops of Canterbury.

One of the interesting features in the building is a niche said to have been created for a statue of Charles I. The church was founded seven years before the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642. Salford and Sacred Trinity supported Charles I and the Royalists. When the Parliamentary side emerged as winners, the church and its tombs were damaged by vengeful roundheads. The interior has been altered. In the eighties the first floor galleries on each side of the nave were glassed in to provide meeting areas. There are some interesting tombs and some striking stained glass. The church still retains its religious integrity which is something that can’t be described but floats somehow in the ether. And then you get to the saddest part; the memorial ‘to the four hundred officers and men of the Salford Battalions of the Lancashire Fusiliers who were killed on the first of July 1916’. That was the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Four hundred dead, one day, one town. By the way, there is an active programme of events in 2016.

.jpg) Sacred Trinity easily missed

Sacred Trinity easily missed

Municipal School of Technology - Whitworth Street

Yes this is a very big building, but it is so often overlooked, maybe because of its bulk that hardly allows a view of it in the tight street pattern around here. Now part of the University of Manchester, this is one of those many Whitworth Street terracotta wonders and was designed by Spalding and Cross. It dates from 1895-1902 and is quite the equal of the Palace Hotel or London Road Fire Station at either end of Whitworth Street.

The external details on this Loire-style giant include superb, if occasionally grotesque, terracotta heads of scholars and mythical monsters. High up, at the roofline, sits the noble Godlee observatory in a copper coat with a dome made of sealed papier mache to ensure it is light enough to be turned to the desired point in the heavens. But best of all push open the doors with their lovely brass Art Nouveau handles on Sackville Street and you get an instant reward. The foyer is alive with glistening tile work underneath a radiant window incorporating a glorious ship inspired by the Manchester coat of arms. Behind the foyer is a stately lower hall with terracotta piers that feels like something from a story with stained glass windows displaying a roll-call of famous scientists, mathematicians, literary surrounded by oak leaves. It’s all pure civic pageantry with an upper hall above dominated by an organ.

The moody and magnificent Lower Hall

The moody and magnificent Lower Hall

Rochdale Canal Warehouse - Dale Street

This building seems to belong in the Pennines rather than the city centre. Or in Yorkshire. Turn through the grand gateway off Dale Street at the Piccadilly Station end of the street and you’ll find to the left an imposing stone building. This handsome four storey warehouse was built in 1806 for the recently opened Rochdale Canal. On the largest side there are broad arches which seem to eccentrically open from dead ground. These originally were the entry points for canal boats to load and offload from within the building. In other words most of the car park from which you are viewing the arches was once a large inland port. This is the oldest surviving canal warehouse in the country. Hidden away in the depths of the building is a high, breast-shot water wheel which served this and an adjacent and long-gone building.

The old stone warehouse all at sea in a car park rather than in water

The old stone warehouse all at sea in a car park rather than in water

The Lazy Workmen Building - Piccadilly

Number 77-83 on Piccadilly by Clegg and Knowles dates from 1877 and is a riot. Literally. It’s as if the famous warehouse designers of Clegg and Knowles were let off the leash with this building. Just under the roofline there is a broad band of strange fruit and vigorous leaves twisting all over the place. Higher again is a timber turret and a hefty gable that could be part of a suburban Tudorbethan semi if it weren’t so huge in scale. But raising a smile for us all are the lazy workmen slouching or snoozing on the cornice, hats pulled low and looking suspiciously like they are suffering off a heavy night. You couldn't find a better motif for the edge of the Northern Quarter.

Get back to work

Get back to work

The Ugly Duckling - George Street

The Guardian network of tunnels under the city opened in 1958. Built by the Ministry of Public Building and Works the tunnels were part of a network of four tunnel complexes intended to be built in London, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow to maintain links with the rest of Nato should the UK be attacked by Soviet atomic weapons. Glasgow was never built. The generators, to keep things going for the exchange workers (as their families burned above), were entitled Marilyn (Monroe) and Jane (Russell) after the stars of the day. They still sit almost 60m (200ft) beneath the city.

There is no public access to these sinister reminders of Armageddon as BT currently runs cabling down them. BT services the tunnels through this ghastly building on George Street. It’s a real terror, functional, drab, surrounded by a high wall crowned with razor wire. It looks and feels very much like something from a concentration camp. As the city centre attempts to polish itself up around St Peter’s Square this ugly duckling squats like a boorish guest who won’t leave a party that finished ages ago.

Bang you're all dead except us

Bang you're all dead except us