THE DOORS of perception, of heaven and hell, of Manchester buildings.

Doors can be both welcoming and sinister, a homecoming or a trial, a welcome or a threat.

For a hundred years architects made a cult of doorways, exalted them and turned them into principal feature of a building

Manchester has some wonderful doorways, portals and entrances although scarce any are a threat, although some might be a warning - we haven't covered Strangeways' old and new entrances here as they're outside the city centre but both make you shudder.

No doubt people will have their favourites in Manchester city centre and think some good ones have been missed. They'd be right but then again this is a personal selection which means I've put in some obvious and some less obvious examples and thus left out Manchester Town Hall.

What is clear is that we're living through a decline in the English doorway. It's been happening since WWII - although some effort was made in the sixties to make them stand out once more as with the Renold Building and the CIS Tower. Generally recent fashions of architecture have dictated portals lie flush with facades, to yield nothing grander than a sliding or revolving door. Efficiency has triumphed.

Even in showy buildings such as the Civil Justice Centre, under all that marvellous drama, the door has become nothing more than a series of glass panels. You can't guess where it is until you walk round the whole building. Same with Urbis.

Civic Justice Centre

Civic Justice CentreMichael Wilford at The Lowry, outside the city centre, clearly felt he needed some flourish with his huge entrance canopy at The Quays but he's the exception rather than the rule.

The golden age of the Manchester doorway comes with the Victorian Gothic (e.g. Reform Club below) and then that crazed pursuit of styles up to the 1930s - particularly with the adoption in Britain of the Baroque (e.g. Atlas Insurance below).

Terracotta buildings in that style seemed very suited to the big gesture at the entrance, such as with the Refuge Assurance below, and its shiny castle. The Refuge is better than London Road Fire Station or The Midland, in my humble opinion, but again you might disagree.

During that hundred year period - roughly 1840-1940 - architects made a cult of doorways, exalted them and turned them into a principal feature of a building. It was like they were saying "Look, we're going to impress all the way and we're starting with first impressions."

If they predominate here then it's because they deserve to do so. Remember this piece is not looking at the value of the building as such but rather the specific qualities of the door, entrance, portal, call it what you will.

The list is in alphabetical order.

ATHENAEUM | MANCHESTER ART GALLERY

Simple, stern, disciplined yet imposing: this is what Charles Barry wanted from the entrance to the Athenaeum on Princess Street. He wanted the very measure of a Renaissance palace from Florence because wasn't Manchester at the centre of a rebirth in Britain, albeit industrial and civic? Behind the entrance the building contained a newsroom, gym, library, lecture hall and billiard room. The building began a trend in Manchester for buildings to look like Renaissance palaces. The 'palazzo' style was born.

Princess Street

Architect: Charles Barry, 1839

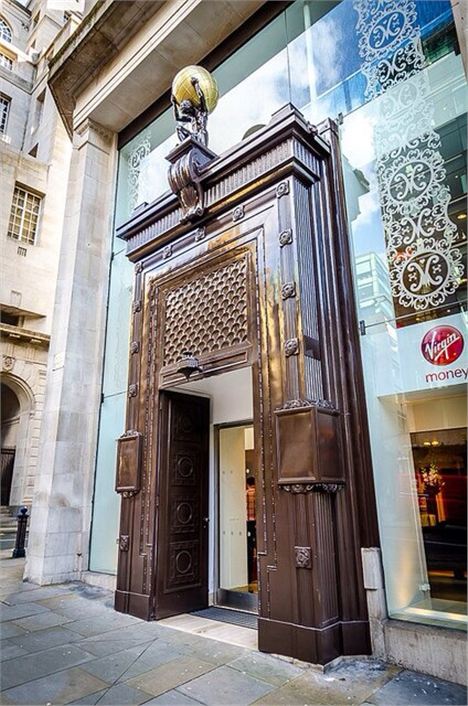

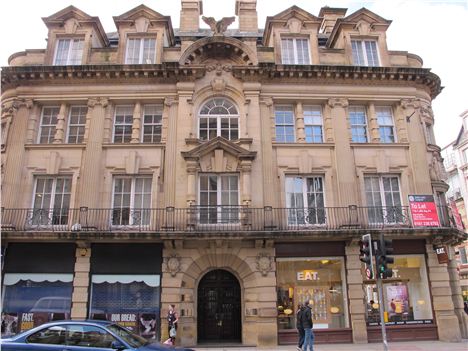

ATLAS INSURANCE | VIRGIN BANK

Ha, look at this thing for Atlas Insurance. This is Britain as though the Empire would never end. It's a building of pure bombast, of imperial confidence, the huge doors almost an anteroom in their own right, thrusting out from the main structure, demanding attention. The whole ensemble is crowned by a mighty Atlas carrying the Earth on his broad shoulders. Probably a lot of Brits at the time thought that's what we were doing.

King Street

Architect: Michael Waterhouse, 1929 (the grandson of Manchester Town Hall architect and see the Refuge Assurance entry below)

Atlas supporting the world on the huge iron doors. Thanks to Barrie Leach for this picture.

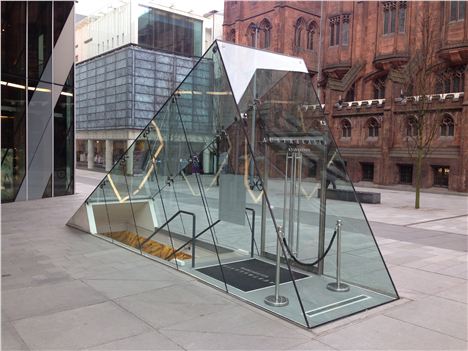

AUSTRALASIA | DEANSGATE

There aren't many modern doorways in this list - see introduction above - but this one stands out for its originality. A little like the glass pyramid at the Louvre this transparent canopy covers a laid out flat entrance. In this case a slice taken out of the pavement leading to the underworld restaurant below. Fun and clever at the same time.

Spinningfields, off Deansgate

Architect: Living Ventures with Michelle Derbyshire

BANK OF ENGLAND (now offices) | KING STREET

This entry is here by default to prove a point because the doorway isn't that grand at all. Charles Cockerell's 1840s bank was free Classical in style, ten years or so later than the purity of true neo-Greek buildings such as Manchester Art Gallery. Such buildings aren't good for this article. In the heavy porticos of Classical buildings the entrance gets lost, the rows of columns in the porticos are an integral part of the whole so the primary significance of the doorway is disguised, subsidiary to the grand design. You can see this in Cockerell's Bank of England on King Street below. The entrance in the middle of the facade was a later introduction to make the building more practical, originally the entrance was via the side and a part but not a key part of the design - as is the way with so many buildings in the last fifty years.

Ex-Bank of England

BROOKS BANK (soon to be Burger & Lobster) | BROWN STREET

In many ways the most delightful of all the fancy Gothic doors. Sir William Cunliffe Brooks wanted his 1868 headquarters to look the part and architect George Truefitt created a beauty. The original entrance is a festival of stone flowers and rosettes carved by Williams and Mooney with ironwork by Bellhouse of Manchester. It turns the corner of the street here with eye-catching yet consummate ease.

46-48 Brown Street

Architect: George Trufitt, 1868

BOMB SHELTER DOORWAY | THOMAS STREET

Up on Thomas Street in the Northern Quarter between two parts of the store called Shopfittings lies an ugly lump of brickwork, painted black, that is built only for strength. This is the door to bomb shelters built in 1939 under the buildings here for local workers. It's a small shelter with a thin membrane wall at the back just big enough to crawl through should the Thomas Street entrance be hit. In other words an escape hatch. The membrane wall is just one brick course thick and came with a sledgehammer. The main bomb shelter door we can see on Thomas Street below might be humble but it carries so much more historical resonance than many a fancier entrance.

Thomas Street

Architect: Unknown, 1939

BYROM STREET DOOR

A series of charming Gothick doorways from the late eighteenth century. Gothick with a 'k' at the end means before neo-Gothic architecture became much more serious in the 1840s. Here think the romantic Gothic of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, think the romantic poets, Byron, Shelley and so on. Certainly they make for fine entrances to what would have been handsome townhouses before being converted for professional use.

Byrom Street off Quay Street.

Architect: Unknown

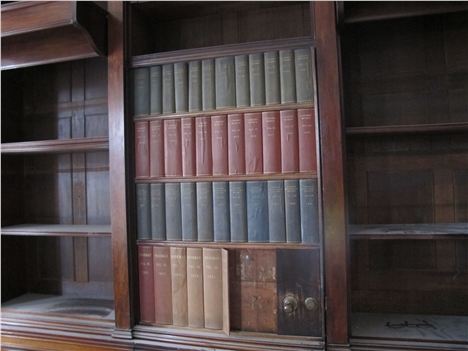

CENTRAL LIBRARY'S FALSE DOOR | ST PETER'S SQUARE

Bit of a cheat this but an oddity too. Yes it's an internal door but it's one of those cunning false ones, this time in the Chief Librarian's office at Central Library. Makes your wonder what the Chief Librarian was sneaking out to do? Romance amongst the shelves?

St Peter's Square.

Architect: E Vincent Harris, 1934

CHATHAM MILL | CHESTER STREET

The mill is part of the complex south of Oxford Road Station. The main building here is a former spinning shed from 1820. The doorway must have been inserted in the 1920s and looks both ridiculous and fetching, a hopeless boast in an ocean of smoke stained red brick and blank windows.

Chester Street

Architect: Unknown, building 1820, door 1920s.

Chatham Mill's curious doorway

CHETHAM'S GATEHOUSE | CHETHAM'S SCHOOL OF MUSIC

Chetham's being the oldest surviving building in the city centre it has the oldest surviving doorways. But let's talk gatehouse this time: doorways writ large. Shown below is the fabulously weathered inner surface of Chetham's School of Music and Library, previously 'The College'. It dates from the 1420s, is built from local stone and seems to have such a sense of permanence and place it have grown out of the ground. There's a staircase to an upper guard chamber which had its own fire. I think Chetham's should let me have that upper office as my own. Guided tours run from there would be grand.

Long Millgate

Architect: Unknown

Chetham's beautiful battered gatehouse

Chetham's beautiful battered gatehouse

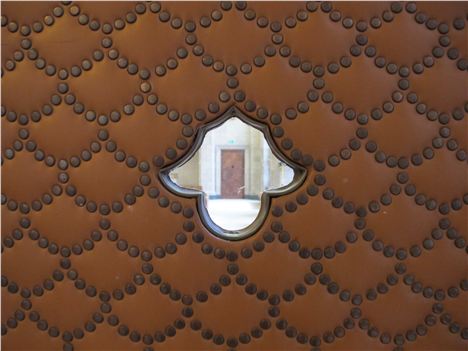

COUNCIL CHAMBER | TOWN HALL

Ok, ok, another cheat as this is again internal, but I adore these elegant yet so of their period doors to Manchester's main council chamber. From the 1930s they look like something from Hollywood of the time, maybe from a technicolor production of Arabian Nights by Cecil B DeMille - if he had been to do one. There is soft tan leather with studs in scallop shapes plus a curious little peep window framing a matching door on the other side of the chamber.

Lloyd Street

Architect: E Vincent Harris, 1938 - although he may not have designed the doors

DALE STREET WAREHOUSE | DALE STREET

The sweet golden millstone grit of this 1806 building is rare for early nineteenth century buildings in Manchester city centre so provides surprise and shock as you walk round Rochdale Canal Basin. Now left high and dry are two water gates into the rear of the building, stranded in acres of car park, cut off from the watercourse that fed them. Boats would have entered these gates and loaded and off-loaded. They are a reminder of how water transport was crucial to the early industrial city.

Dale Street (walk into car park to view the gates)

Architect: probably William Crosley, 1806

EAGLE STAR HOUSE | CROSS STREET

This is a sweet office block from 1911 for Eagle Star Insurance from one of Manchester's most assured architects of the period, Charles Heathcote. Here he's designed a Baroque building full of chunky motifs and a doorway that, in effect, goes through all the levels and is capped with an eagle. You can see influence in some of these doorways around the city from earlier times when the entrance was a source of inspiration and an opportunity to show off as in the Tudor entrance to Lyme Hall in Disley.

Cross Street

Architect: Charles Heathcote, 1911

J&J SHAW | NEW WAKEFIELD STREET

This building needs a bit more research - or if somebody has researched it, could you let me know who designed it? Did it host a company that wholesaled flowers or fruit? What is clear is the date 1924 and how it displays company pride in a manner that illuminates a narrow street hemmed in by railway arches. Well done J&J Shaw.

New Wakefield Street

Architect: Unknown

LAWRENCE BUILDINGS | MOUNT STREET

Here's one of Manchester's early Inland Revenue buildings. By Pennington & Brigden from 1874-6 it is full of detail. There's a Queen Victoria statue in the wall high up but around the door are those symbols of Crown authority, a beautifully executed Lion and Unicorn.

2-4 Mount Street junction with Central Street

Pennington& Brigden, 1874-6

LANCASTER HOUSE/INDIA HOUSE | WHITWORTH STREET

It's probably naughty to include this as with one or two others here but this elegant gate designed by Harry S Fairhurst is superb. When closed it describes a perfect circle. Hanging from the middle like the pendant on a necklace is a jewel-like lamp, twisted in a manner emblematic of Art Nouveau.

Whitworth Street

Architect/Designer: Harry S Fairhurst, around 1906

PEVERIL OF THE PEAK | GREAT BRIDGEWATER STREET

This pub was built in the early nineteenth century and would have been standard red brick. Around 1900 the owners must have thought a revamp was in order. So they covered the whole building in iridescent green tiles, Art Nouveau lettering and ornate door surrounds. In otherwords they upped the advertising and created a jewel for the city centre.

Great Bridgewater Street

Architect: Unknown

PICCADILLY PLAZA & HOTEL | PICCADILLY GARDENS

It's a right rum one this madness of a brutalist lump. But as time moves forward it does become more and more heroic. The door might be hard to pick out under that huge projecting cantilever but as with other older entrances and portals it's designed to be a mere part of lofty gate motif that drags the eye higher and higher.

Piccadilly Gardens

Covell, Matthews & Partners, 1965

All of a piece of a huge portal

All of a piece of a huge portal

REFUGE ASSURANCE | PALACE HOTEL

The current Palace Hotel was built in stages from 1891 to 1932 for the Refuge Assurance company. During this time the entrance migrated down Oxford Street and under a huge arch. The original entrance is still best though, sporting a castle gatehouse to show your money was safe with the company. As with Eagle Star House above, the doorway makes its presence felt all the way to the top dome. Inside is one of Manchester's most exquisite tiled surfaces with scallop shells and the entwined initials of the company.

Oxford Street junction with Whitworth Street

Architect: Alfred Waterhouse 1891-5

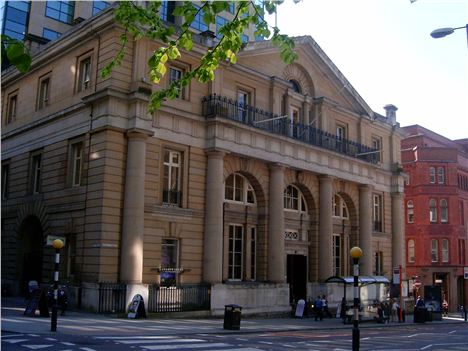

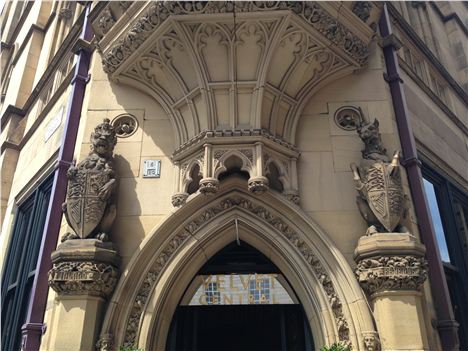

REFORM CLUB (former Room restaurant) | KING STREET

Edward Salomons loved it Gothic and loved it crazy. In this largely Venetian Gothic style Liberal Club he clearly felt liberated enough to chuck everything at it, relief sculpture, finials, tilework and gargoyles. The entrance supports a balcony from which William Gladstone, Winston Churchill and Lloyd George (not Boy George as someone once stated in error) spoke to party members and the public below. This is Gothic architecture as pure fantasy, almost filmic in its excess. Living Ventures recently bought the building following the collapse of Room restaurant.

King Street

Architect: Edward Salomons, 1871

Fantasy and craft. Thanks to Barrie Leach for this picture.

RENOLD BUILDING | UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER

Designers such as Cruickshank & Seward and WA Gibson in the 1960s in the UMIST buildings (now part of the University of Manchester) seem to have had as much fun as Salomons in the Reform Club. The former UMIST area just south of Whitworth Street is a lexicon of International Modern elements with walkways, undercrofts, murals and of course acres of concrete. At the Renold Building the entrance is a bridge over a service road beneath, there's almost something medieval and castle-like about it. It's great fun and sort of thrilling to be entering a building over fresh air.

University of Manchester, Sackville Street campus

Architect: WA Gibson, 1962

Renold Building, walking on air

Renold Building, walking on air

WATTS WAREHOUSE (Britannia Hotel) | PORTLAND STREET

Another grand Victorian warehouse entrance but good enough or distinctive enough to be included here? Perhaps not, but as a doorway and entrance it has rare treasure hidden just behind. On the south side lies Charles Jagger's superb sculpture of an indomitable British Tommy standing foursquare and solemn. The sculpture, one of the best war memorials in the country, marks the sacrifice of many employees from the Watts textile company. There's other weaker statuary from after World War Two. Sadly Jagger's work has been attacked, no doubt some hen or stag party at the Britannia Hotel thought it a right laugh to steal our hero's bayonet.

Portland Street

Architects: Travis and Mangnall, 1858. Sculptor: Charles Jagger, 1921

Standing guard

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+