SO Scotland in a few days time might break the family tie. Given Manchester’s links with Scotland – let alone those with the rest of the UK – this is desperately sad.

The city has been full of over-achieving Scots for more than 200 years.

The role of many communities has been highlighted in Manchester by many other commentators - German, Jewish, Irish, Greek, Italian and latterly Asian, Black and Chinese - but the most influential has been Scottish.

The first Scot to make an impact under-achieved. This was Bonnie Prince Charlie who with his tartan army passed through in an attempt to wrest the crown from George II in 1745. Artillery Street in the city centre, off Quay Street and Byrom Street, marks the spot where he practised his canon. He failed miserably although several foolish Manchester men who joined him would be hanged, drawn and quartered and their heads put on the Manchester Exchange.

Bonnie Prince Charlie

A little later Aytoun Street got its name from Roger Aytoun, a Scot who came down to Manchester in the 1760s and swept Barbara Minshull (hence the parallel Minshull Street) off her feet. He was in his twenties, she was in her sixties. She was also the richest widow in the town. Tongues wagged. Aytoun was famous for scrapping in pubs and his nick-name was Spanking Roger. Eventually he drank and gambled the money he inherited from his venerable wife away and returned to Scotland.

But the real Scottish influence began when a legion of businessmen and engineers came south to seek their fortune in Manchester in the early nineteenth century. They knew the place was a magnet for entrepreneurs.

Plaque to the Murray family in Ancoats

Four such Scots were William McConnel, John Kennedy and brothers Adam and George Murray, businessmen who seemed to make money wherever they turned.

Their surviving cotton mills along Redhill Street and the Rochdale Canal in Ancoats have now been converted into offices and apartments. These structures amazed the world when first built, defining a new way of living. German architect Schinkel when he visited in 1825, wrote, 'Here are buildings, seven to eight stories high, and as big as the Royal Palace in Berlin.'

One of the greatest British engineers of all time also settled in Manchester from Scotland. Sir William Fairbairn, the engineer, who perfected boilers so they didn't blow up every few years, designed factory machinery and claimed to have been the engineer behind nearly a thousand bridges including the famous tubular Menai Straits bridge connecting Anglesey with mainland Wales.

That Fairbairn bridge

Much of the success of his civil engineering was down to his collaboration with Eaton Hodgkinson, and the pioneering of an efficient H-girder, which altered and adapted, still holds up the world’s buildings.

Another Scot boiler-maker, engineer and industrial pioneer was William Galloway. His company’s collaboration with Henry Bessemer at their foundry in Knott Mill, Manchester, led to the Bessemer Process, perfecting the manufacture of steel. As with the H-girder, this helped create much of the modern world.

As a commentator said in the early nineteenth century: ‘It was rather remarkable that nearly all the original millwrights in Manchester came from the neighbourhood of the Tweed... All were Scotchmen – quiet, respectable and mostly middle aged, with experience, for in those days a man was not put to mind one machine year after year. He had to understand pretty nearly the whole process, from taking particulars and making patterns, to fixing machinery in the mill.’

Another of these 'Scotchmen' was James Nasmyth who made his mark as the inventor of the steam hammer at his factory in Patricroft.

Many of these engineers and industrialists played a major part in the cultural life of the city. Fairbairn for example was the president of the Manchester Literary and Philosphical Society. Another member of the society was James Young, a Manchester-based Scot, who became well-known for distilling paraffin from coal and oil shales: a sort of proto-fracker.

Charles Macintosh of Glasgow formed an alliance with Mancunian Thomas Hancock in 1830 and together they started to manufacture the Mackintosh on Cambridge Street in the city, spreading the popularity of the waterproof, rubberised coat across the globe.

There were big Manc Scots in medicine too.

James Braid lectured in the Athenaeum on Princess Street, now part of Manchester Art Gallery in 1841, and introduced the word ‘hypnotism’ to the word. This led from his studies of what had been called 'mesmerism'. He was also an innovator in the treatment of club foot.

Earlier John Ferriar from Jedburgh had been a pioneer in improving sanitation across the city and within medical institutions. He fought gainst child-labour, advocated the use of foxglove in medicine and the opening of public baths. He wrote a four volume history of medicine.

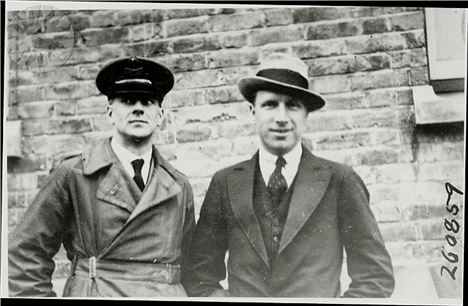

John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown were the first to fly across the Atlantic non-stop in 1919. Brown was born in Glasgow but was raised in Manchester and has a plaque marking this on his old family home at 6 Oswald Road, Chorlton.

Brown on the left, Alcock on the right

Brown on the left, Alcock on the right

Latterly the achievement of Scots in Manchester sport has been notable, especially in football and especially at Manchester United.

Manchester City line-ups have featured Scots such as Willie Donaghie, Denis Law and Sir Matt Busby - but the latter two were always more associated with United.

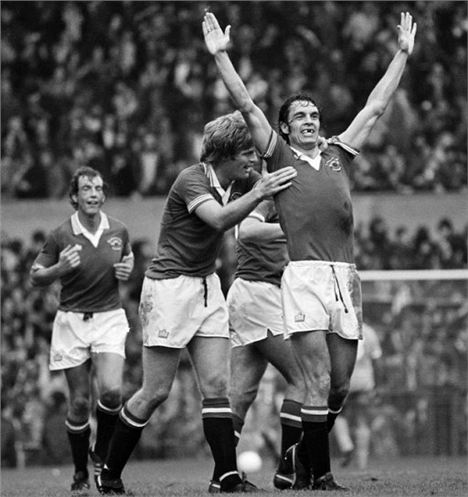

MUFC have featured Scots footy players sucha as Willie Morgan, Pat Crerand, Martin Buchan, Joe Jordan, Gordon McQueen, Lou Macari, Gordon Strachan, Brian McClair and Darren Fletcher.

Joe Jordan celebrates at Old Trafford

The Irish might come over in their droves to watch United but it is the Scots who have been far more influential on the team. Sir Matt Busby was the manager for more than two decades, while Tommy Docherty won the FA Cup in the seventies.

In recent years the dominant United Scot has been Sir Alex Ferguson, the most successful manager in British history and a man who’s also been actively involved in the city’s social and cultural scene.

Apparently there was a Scot called David Moyes who did something somewhere - anybody remember him?

Finally with sport it was Chris Hoy in Manchester who did so much to make British track cycling our most gold-heavy Olympic sport of recent years.

Chris Hoy

The Scots are still lead performers in cultural life. Alex Poots is the Director of Manchester International Festival, Since 2007, he has masterfully crafted a critically acclaimed biennial with global-pulling power.

Alex Poots in Albert Hall

Another cultural contemporary is the current Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy. As one of her biographical references describe, she is 'the first woman, the first Scot, and the first openly gay person to hold the position'. She is a Professor of Contemporary Poetry at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Nor should Dr Jimmy Grigor be forgotten who as the chair of Central Manchester Development Company in the 1980s kickstarted the regeneration and active use of a huge area of central Manchester strung along the Rochdale Canal from Castlefield to Piccadilly.

Carol Ann Duffy

Of course there has been a dark side too to the Manchester and Scotland link. Ian Brady, the monster of the Moors Murders, came to the Manchester area from Glasgow in the late fifties as a man in his early twenties.

That aside, this article is about the shared history, the entwined stories of Manchester and Scotland. It's a celebration.

The role of many communities has been highlighted in Manchester by many commentators - German, Jewish, Irish, Greek, Italian and latterly Asian, Black and Chinese - but the most influential has been Scottish.

Perhaps the reason for the lack of examination is because England and Scotland are composed of essentially the same people, the same culture (with occasional nuances of difference) so the contribution does not seem as remarkable. Nobody has crossed the sea to get to Manchester from Scotland (well maybe a few from the Hebrides). None of our achievers in the list above had anything other than English as their first language.

Let me explain this.

Manufactured culture gets in the way of people seeking common ground. It forces them apart.

Thinking of Scotland most of us think of kilts, bagpipes and peaty landscapes where everybody goes by the name of Mac. That ‘Highland’ image, manufactured in the late 1700s and through the 1800s has always represented a tiny proportion of Scotland’s population. Mostly the image is just corney sentimentalism.

None of our Scots listed from the nineteenth century in the article above were Celts, mostly they were southern Scots whose families had always spoken English – albeit the English of Rabbie Burns. They were Anglo-Saxon and Norse. They would never have dreamt of wearing a kilt.

As for that kilt, the short version now used by anybody with any passing Scottish connection attending a wedding was invented by a Lancashire man, Thomas Rawlinson, who went to the Highlands in the 1700s to set up an iron works. The kilt at that time was a long piece of material that reached the floor and was unsuitable for industrial work so Rawlinson cut it to knee-length in an early health and safety initiative. He was sick of seeing his workers going up in flames.

Hey, Sean, how's the Lancashire kilt doing?

The NW has more than 7m people, Scotland has more than 5.3m. Scotland’s landscape is wilder in the north than the south, so is the North West’s. Scotland has two dominant cities separated by 46 miles, Glasgow and Edinburgh. Liverpool and Manchester are separated by 35 miles.

Manchester, clearly has much more in common with Glasgow than it has with Dorset or for that matter Dortmund, and Glasgow has much more in common with Manchester than it does with Wick or for that matter Marseilles.

The similarities are clear.

Back in the 1400s Manchester Cathedral received a gorgeous timber roof. Up there, still visible today, are carved angels playing instruments. Two of them are playing bagpipes.

The common roots of most of Scotland with most of England - and especially our bit of England - run very deep. The truth is we’re the same people in the same country.

Discuss, a forward-thinking Manchester debate forum, will tackle the Scottish referendum at 'Manchester's Message To The Scots' - Manchester Town Hall, Wednesday 17 September, 6.30pm

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+

Happier together