Councillor John Blundell on why historians should never become town planners

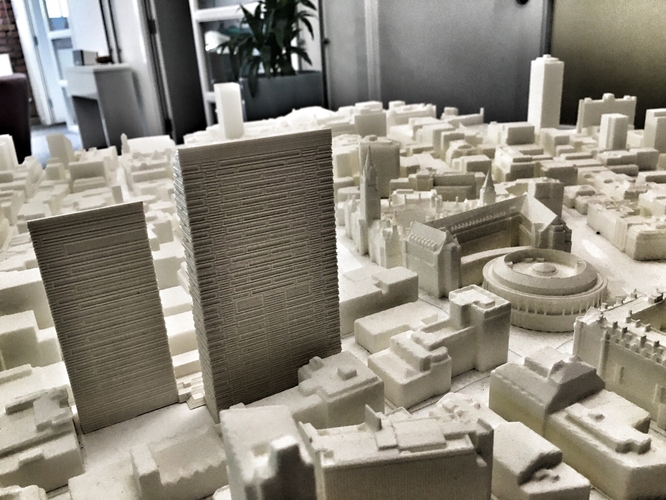

In July, following a volley of criticism from all angles and the removal of their chief architect, the Gary Neville-fronted St Michael's partnership released a new set of proposals for the 1.5 acre site off Albert Square. The contentious twin 'rabbit ear' towers had gone, as had the multi-level plaza and the 'Spanish stairs' to nowhere. In their place stood one single (and more sensitive) glazed tower, two reduced subsidiary blocks and public rooftop gardens. The partnership also promised to save the doomed Abercromby pub and Bootle Street Police Station facade.

More than 400 people visited the public consultation for the new Hodder+Partners scheme, with the St Michael's partnership proudly announcing to press that only 10% opposed the revised plans, with over 84% in support, one way or another. Eager to get the public on-side this time around, Neville and co. will provide the public with a second opportunity to see the latest proposals in the Royal Exchange later this month (11am-7pm, Weds 23 Aug) - including new designs for that landmark tower.

One man who isn't so pleased with the new proposals is Rochdale councillor and planning and housing committee member, John Blundell, who says he speaks for many others who believe the partnership has, by bowing to naysayers, done the city a disservice.

The recent series of events that culminated in the drastic changes made to the plans for the ‘Gary Neville’ development have been greeted with outright glee. However, I – along with many others – am not so happy about where we have ended up. We could have had a development that was iconic: audacious lighting up our skyline, reinvigorate our Mancunian cityscape. Instead what we have is something which is, by design, unassuming, unnoticeable and more-or-less invisible. It is a monument to mediocrity and a perfect example of why historians should not be town planners. When you set out on a consultation, the aim is to canvass the opinions of a wider audience, not simply to capitulate to the naysayers - the vocal minority. Nobody responded to the consultation exclaiming that what they really, really wanted was something so mind-numbingly mediocre.

Chicago is one of my favourite musicals. One of its best songs, Mr Cellophane, is about a quiet man who has to face the fact that he remains unnoticed whilst his murderess wife receives nationwide attention for her crimes. The song makes you feel sad for somebody who shouldn't be so unassuming, unnoticeable and invisible at such a difficult time. I propose that Mr Neville’s new development from here on in be nicknamed 'Cellophane'.

The majority of Mancunians were not as against the plans as the campaigners would have you believe.

That Manchester appears to have opted for something so tame – the safe, middle-of-the-road option – seems to me like a violation of everything that has made the city what it is today. A city famed for its inhabitants’ swagger and its number of world firsts is choosing to allow itself to become a museum, forever fossilised in the past. This is why, for those of us who believe that a city’s buildings are a reflection of its people, we must fight back with a voracity equal to those who fought against the original plans. The majority of Mancunians were not as against the plans as the campaigners would have you believe.

I am not saying that we should have stuck with the original plans, but we needn't have gone the whole hog in the other direction. In order to settle this row over where buildings should be placed, what they should look like and how individual they should be, it might be instructive to draw upon the experiences of London and Paris.

Paris is famed for its beauty, culture and cuisine. London, on the other hand, is a truly global city, which boasts one of the most productive work forces in the world and a city centre denser than almost anywhere else on earth. The two cities are largely comparable, except that one has chosen to fossilise itself and the other has displayed a willingness to adapt and evolve in line with an ever-changing world. London is the more successful city of the two because it is the latter.

La Défense is more comparable to Poplar than it is to the City of London. It is out in the Parisian sticks, exiled to the fringes of the city so as not to disrupt its historical centre. The result: a city that is more attractive to tourists than the people who actually live there. Paris may be a wonderful place to visit and it may look the part on a postcard, but its economy has never been as successful as its British counterpart because its planners chose to separate its jobs and people from its heart. Remember, some 400,000 Frenchman live in London.

For those who have visited Poplar in London – most commonly referred to as Canary Wharf – it feels cold and overly modern. It is lacking in any history or character largely because it was built on a old dock, with nothing of note to preserve. A friend, who worked there during the early stages of its development, told me stories of how difficult it was to get to. She recalled that sometimes she even had to get a boat across the Thames to get to work in the morning. It took millions of pounds of taxpayers money to install the Jubilee Line Extension (JLE) that would allow the area to continue to grow. The most recent instalment of our money – a cool £15bn worth – will come in the form of Crossrail.

An unfortunate consequence of their campaign has been to strengthen the case to preserve Manchester as it is and deny what could be

Poplar reminds me of La Défense: a cluster of employment without a soul. For this reason, of course, those who argued against the Neville development in its previous form – laying waste to the Old Police Station and Sir Ralph Abercromby Pub – were quite right to try and preserve a part of our history. But an unfortunate consequence of their campaign has been to strengthen the case to preserve Manchester as it is and deny what could be. We have been left with a man made monstrosity; a patchwork quilt reflecting the excesses of public opinion.

For a city to be successful, it must have the right blend of the old and the new. On the one hand, a healthy respect for its history and its inhabitants’ collective inheritance – bricks-and-mortar reminders of the ways in which a city’s past continues to exert a powerful influence on its present. On the other hand, a city must never be afraid to embrace progress. Innovative, imaginative and daring new buildings herald the arrival of the future. We should look to preserve that which has made our city great in the past but, at the same time, we should also look to erect a new set of iconic structures that our descendants will want to preserve.

It is my firm belief that the vast majority of Mancunians do not want to see our city centre monopolised by an endless parade of identical glass buildings; we want an exciting, unique and impressive skyline, one which reflects the attitude of this great city. And to those who make it their life’s mission to rail against anything architecturally challenging or unique, might I suggest a drink with Mr Cellophane?

Councillor John Blundell:

John Blundell is a graduate of economics at the University of Manchester and was elected to Rochdale Borough Council at the age of 20. He has worked as a transport and development economist both for a niche firm London and a large practice in Manchester.

He campaigns on trying to change the life chances of young people both through literacy and art but is now using his professional skills to better inform the debate on city economics in Greater Manchester.