THERE’s an eerie silence as I make my way along the trench. Stepping carefully on the duckboard beneath me, I follow the twists and turns along the route.

I stop and close my eyes, leaning against the corrugated iron and sandbags that hold back the earth. And I picture myself, tired, cold and ankle-deep in mud, waiting to do my bit for King and Country.

'There’s a gradual hush as the buglers of the Last Post Association take their places and their notes pierce the evening air. As I close my eyes I remember the sacrifice made by so many brave men – and take comfort they will always be remembered'

Stepping on to a ledge for a view from my subterranean refuge, I imagine that I’m standing on a makeshift ladder. How terrifying it must it have felt to be poised, waiting for the whistle to blow to signal that it’s time to go ‘over the top’.

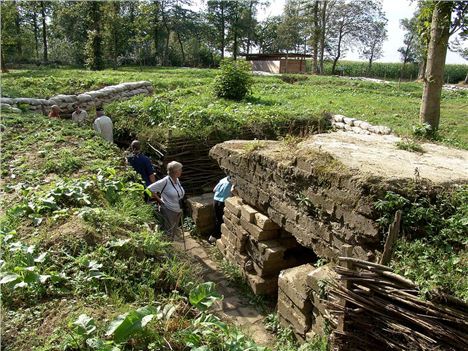

You can tour museums and wander through war cemeteries for an insight into the events of World War One – but being in a trench, albeit a reconstructed one that comes minus death, mud and vermin, is a sobering experience.

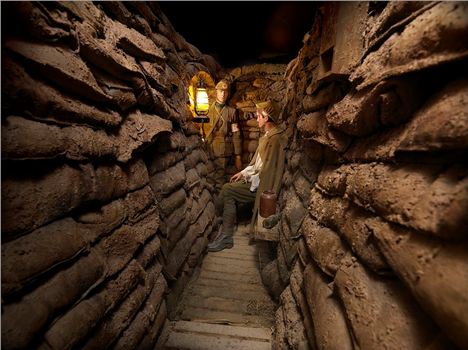

Visiting a bunker; below, a museum recreation of life in the trenches

Visiting a bunker; below, a museum recreation of life in the trenches

This network of open-air trenches can be explored at the Passchendaele 1917 Memorial Museum in the grounds of the Zonnebeke Chateau, not far from the Belgian city of Ypres – a name synonymous with the Great War.

As we approach 2014, Belgium is preparing to mark the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War. Many museums have been given a facelift in preparation for the expected influx of visitors eager to learn more about the conflict.

The British are given a warm welcome here and we can witness how our forefathers are remembered with pride. We may have grandfathers or great-grandfathers who died on the battlefields of Flanders but whatever our personal history, it’s a moving experience to trace the footsteps of a lost generation.

The museum at Zonnebeke reopened in July with the addition of the open-air trenches and a new underground section focusing on the Battle of Passchendaele, which claimed 500,000 casualties in 100 days for the gain of just a few kilometres of territory.

The story of the Great War, which cost the lives of 10 million and saw many more wounded, mutilated and traumatised, is told in the recently refurbished In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres.

Flanders Field Museum; below, telling the story of the war vividly

Flanders Field Museum; below, telling the story of the war vividly

Housed in the majestic Cloth Hall in the market square, new technology enables the visitor to interact with the mass of exhibits on show.

You are given a ‘poppy’ bracelet containing a microchip which, when placed against a specific symbol, prompts a series of personal stories. I discovered that scientist Marie Curie, who shared my Polish roots, played a significant role in the conflict.

These stories, and the imaginative way in which such a staggering amount of information is presented, makes the museum an ideal starting point from which to discover more about the First World War and its legacy.

Wherever you venture in the rolling countryside surrounding Ypres, termed ‘Wipers’ by the British soldiers and now known by its Flemish name of Ieper, there are reminders of the conflict. The area is dotted with hundreds of military cemeteries, monuments and war relics.

Paschendaele's Tyne Cot Cemetery

Paschendaele's Tyne Cot Cemetery

Among these is Tyne Cot – the largest Commonwealth War Graves cemetery in the world. There’s a sense of peace here as you stroll around row after row of headstones marking the graves of 11,956 Commonwealth soldiers.

Equally moving is the screen wall at the back of the cemetery that commemorates a further 34,957 missing soldiers who died after 15 August 1917. The more than 55,000 missing who died before this date are named on the Menin Gate memorial in Ypres.

The gentle air of calm continues at the Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery where 10,784 soldiers are buried. An evacuation hospital once stood here – the casualties arriving by train.

The devastated landscape created by the Great War

The devastated landscape created by the Great War

The visitor centre, designed to resemble the huts where the sick and injured soldiers were treated, tells the story of the hospital. The first thing you see is a calendar with the details of someone who died on that particular day and how to find their final resting place.

There were, of course, casualties on both sides. A total of 134,000 German soldiers from the Great War are buried in Belgium, including 44,304 at Langemark. The site includes a mass grave in which 24,917 casualties were buried.

The numbers say it all – so many lives lost – and it’s hard to imagine what life was like for the troops, many still in their teens, encouraged by the propaganda of the time.

Inside The Talbot House at Poperinge

Inside The Talbot House at Poperinge

There was, however, some respite from the horrors of the trenches. In the town of Poperinge, behind the front lines, Talbot House offered a refuge for soldiers regardless of rank.

Two army chaplains opened the ‘club’ in the former home of a local hop trader and here the troops could regain some semblance of normality. Today, visitors can tour the house and grounds and learn more about life away from the fighting.

Poperinge, or ‘Pops’ as it was affectionately termed, provided plentiful entertainment for the soldiers of the Great War and almost 100 years on it’s still a charming place to visit.

Surrounded by hop fields, Poperinge has close connections with the brewing industry. There’s the Hop Museum in the centre of town, full of interesting exhibits, where you can sample a glass of Poperinge Hommel Bier (hop beer) or any other of the local brews that takes your fancy.

How different life in the town must have been from that in nearby Ypres, which was all but razed to the ground as a result of constant bombardment. Surveying the main square, it’s hard to believe that the elegant buildings have all been reconstructed.

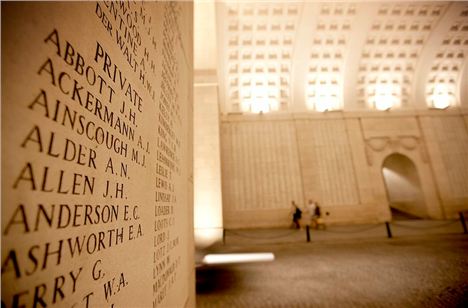

Menin Gate, Ypres; below, its roll of honour

Menin Gate, Ypres; below, its roll of honour

But perhaps the most poignant building in Ypres is the Menin Gate. This imposing monument stands on the site of one of the old town gates through which tens of thousands of soldiers passed on their way to the front – many never to return.

The memorial bears the names of 54,896 soldiers who were reported missing in the Ypres Salient, a semi-circular bulge in the front line, between the outbreak of war and 15 August 1917.

Every day at 8pm crowds gather at the Menin Gate to witness the sounding of the Last Post. There’s a gradual hush as the buglers of the Last Post Association take their places and their notes pierce the evening air. As I close my eyes I remember the sacrifice made by so many brave men – and take comfort that they will always be remembered.

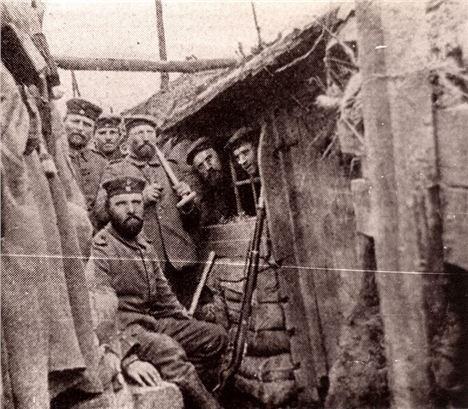

In the trenches thousands met their death

In the trenches thousands met their death

Fact file

Belinda Szonert was a guest of P&O Ferries and Visit Flanders.

Prices for a five-day return ticket with P&O Ferries start at £109 each way for a car and two passengers on the overnight Hull-Zeebrugge service including a two berth inside cabin. P&O Ferries also operates the short Dover to Calais crossing with a five-day return ticket starting at £30 each way for a car and up to nine passengers. Further information and reservations at www.poferries.com or by telephoning 08716 64 64 64.

For more information about travelling to Ypres and the Flanders Fields see www.visitflanders.co.uk/discover/flanders-fields/

Relevant Websites:

Talbot House www.toerismepoperinge.be/en/page/3021/sleeping.html

Lijssenthoek Cemetery www.lijssenthoek.be/en

Memorial Museum Passchendaele www.passchendaele.be/eng/homeEN.html

We stayed at the Novotel, Ypres. Rooms start from £75 per room per night on an early bird deal.

Restaurants:

We ate at Defonderie. Set menus for lunch start at €14 for two courses and at Brasserie Kazematten which is part of the St Bernadus Brewery, Watou (www.sintbernardus.be/)