WAY towards the end of John Grindrod’s hefty book (something titled Concretopia was never going to be a slip of a thing); enter Ray Fitzwalter, two-times BAFTA winning television journalist, legendary editor of World In Action, sitting in “a cosy stone cottage overlooking Manchester, as though he were still policing the North”.

Now he’s drinking tea with his mum, by the fountains on the Lakeside Terrace at the Barbican, whose three residential towers are still the tallest concrete structures in Europe.

In the late sixties Fitzwalter was a young journalist on the Bradford Telegraph and Argus. Sitting in an office in Pontefract on the other side of Leeds, was the head of the biggest architectural practice in Europe at the time, a baby faced crook called John Poulson. “Ray recalled that on meeting the mayor of Bradford, the property tycoon [Poulson] had remarked: “I think you look a bit peaky. You need a good holiday, lad.” A few days later tickets arrived for a foreign break for the mayor and his wife.”

And so on, all the way up a vast, largely Masonic construction of conspiracy, fraud and corruption that ran from police, local government, civil servants, politicians, business and press to the Cabinet Office itself, like mould through particularly smelly blue cheese.

Eventually Fitzwalter did for Poulson and his crony T. Dan Smith, the leader of Newcastle council. If you don’t know the story (and you haven’t seen the great late nineties TV drama series Our Friends In The North that draws on it) read this book.

And read this book for a dozen other reasons.

For Hulme the bell tolls: Hulme before it bit the dust, thirty years after being built

Its subtitle is “A Journey around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain”, and it is a journey conducted by a charming man, who does not hide his mid-century geekiness (he gets very excited about the pre-digital knobs and dials in forgotten bits of London’s Post Office Tower).

He introduces us to his witnesses to post war riches in the politest of terms. We even meet his partner, Adam. John’s a lad from Croydon, and off he goes hunting Prefabs, Garden Cities, blitzed Plymouth and Coventry, Brutalist schools, Streets in the Sky, Tower Blocks, Ronan Point, Tricorn, Arndales and Cumbernauld.

You might as well leave the bus now if the sight of concrete puts you off, or the very thought of pedestrian underpasses makes you queasy, or Milton Keynes is your idea of a bad joke. John Grindrod set out to meet the people for whom these random slubs in the fabric of modern life had rhyme and reason.

There’s a man in the middle of Concretopia who is living in 1957. Or, at least, he is giving it a good go. He’s called Oliver and he is the proud owner of a deceptively mundane flat in Parkleys, an estate in Ham Common, west London.

Oliver won’t have a toaster – too modern – would love to afford a reconditioned 1950’s fridge, does have a lot of mid-century Scandinavian teak furniture. His flat is the work of developers called Span, and their architect Eric Lyons: “The kind of modern design Eric and Span were championing was somewhere between expensive architect-designed villas for the rich and rational large-scale council developments for the working class.”

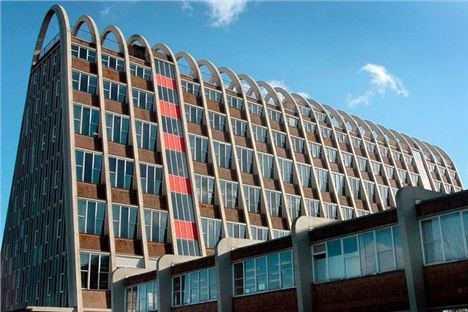

Fort Ardwick in Manchester, another concrete 'desaparacido'

Fort Ardwick in Manchester, another concrete 'desaparacido'

Span mecca is New Ash Green, Kent. Check out the web site, rather as our guide checks out the mono-pitched roofs, half-tiled frontages and the original features of the house belonging to Patrick, a university lecturer who has lived here since he was four years old, “the big white porcelain sink, brushed aluminium door handles, the black ceramic tiles in the bathroom and the yellowing plastic light switches and power sockets”.

Rather as your therapist might gently talk you through your worst nightmares, so John Grindrod quietly elicits tales of Harlow and Cwmbran, Cumbernauld and Elephant and Castle, from planners, architects and residents.

His witnesses are gentle, soft-spoken, quick-smiling well intentioned people whose best laid plans, very often turned to concrete powder, or hard core for airport runways, as with Basil Spence’s Queen Elizabeth flats in Glasgow. They were blown up in 1993, less than 30 years after they were opened. To former resident Eddie McGonnell, they were his beloved Queenies, and Basil Spence the scapegoat of a derelict city council.

John Grindrod ends up back in London. He’d spun us around the Dome of Discovery, up the Skylon and through Festival Hall in 1951. He’s unravelled the labyrinthine innards behind the gracefully stacked terraces of the National Theatre. Now he’s drinking tea with his mum, by the fountains on the Lakeside Terrace at the Barbican, whose three residential towers are still the tallest concrete structures in Europe.

As he wrote his book, Preston Bus Station was still threatened and is given honourable mention here, as are, 'Liverpool’s glorious Metropolitan Cathedral and the exuberant Toast Rack in Manchester'.

Manchester's Toastrack

It will be clear that this is a book for the 20th Century Society and The Manchester Modernists, but let me persuade you of its far wider appeal.

One of the great literary achievements of the last few years are the five books so far published in historian David Kynaston’s mighty project, Tales of a New Jerusalem, a sequence of books about Britain between 1945 and 1979: between the end of the war and the beginning of Thatcher’s first government. By the end of book five, he has reached 1959. I hope we both live long enough to complete the project. So saying, Kynaston’s latest volume, Modernity Britain, is perfectly complemented by Concretopia, a companion book equally entertaining and hugely informative.

All the anti-modernist bête noire are here, in addition to some that have escaped sneering. The writing is relaxed and John Grindrod wears his scholarship rather as an open-necked shirt.

This being Concretopia, we were bound to take a turn around Park Hill, that modernist mountain leering over Sheffield. We’ve walked its Streets in the Sky in the favourable company of former residents and janitors.

Park Hill is lately undergoing a phased refurbishment by Manchester’s own Urban Splash, about which, in his conclusion, Grindrod says this: “And then there’s that third of Park Hill which has suffered the least sympathetic makeover since Ally Sheedy was tarted up in The Breakfast Club”. I had to look that up. It made me laugh. I should like to meet John Grindrod, should he ever want to take a stroll around Wythenshawe.

Concretopia: A journey around the rebuilding of post-war Britain by John Grindrod is published by Old Street and is priced at £25.

Concretopia