“WHY do you do this?” I ask.

As a developer, who lives in the city, I have to be comfortable in my own mind that what we are putting there is better than what we have already

“I don’t know sometimes,” says Gary Neville with a burst of laughter. “I said to one of my lot last week, why didn’t I, after my football career, just get paid to talk about it on telly, then come back into Manchester and sit in a bar and relax?”

He pauses and leans forward.

“The reality is I want to do everything. I want to do Salford City, St Michael’s, the Stock Exchange… I want to make people think these are fantastic projects. But I only want to do projects that I love, the primary reason is not to make money. If I’m not interested then I won’t do it.”

Salford City is the amateur league football team Neville and other ex-United colleagues are attempting to get into the Football League. The Stock Exchange is Neville’s dream of creating a centre of eating excellence and a boutique hotel just off Market Street in the former Stock Exchange. St Michael’s is the lofty development close to the Town Hall and the reason for this interview, which includes a 200-bed five-star hotel, 153 apartments, 135,000 sq ft of Grade A offices, loads of public realm and a replacement synagogue.

CGI of St. Michael's upper square

CGI of St. Michael's upper squareThese are just some of Neville’s many business concerns, Hotel Football is another, all of which he heads up as part of a consortium backed by, amongst others, Singaporean billionaire Peter Lim. Oh, and previously he was a footballer. You may have heard. More of this later.

First let’s be swept along in the passion of the Neville rhetoric.

“At the moment I want to do these projects because things such as the Stock Exchange excite me like you wouldn’t believe – I know how Manchester Confidential has written about the chef (Michael O’Hare) who is fantastic. The fact the site of the Stock Exchange presents challenges is something I want to see if we can resolve, I like that challenge. I think the proposals for St Michael’s from Ken Shuttleworth of Make Architects wow me, there are challenges ahead but as a developer you expect that.” Shuttleworth was the designer of London’s Gherkin while working in Manc-born architect Norman Foster's practice.

Gary Neville’s answers to questions rush out in a flood of sentences that are very different from the considered and careful responses I’ve received from numerous property developers over the years. Neville seems to want us to believe his motives are sincere along with his love for Manchester, and he seems to care whether we care.

And we do care, sometimes for his liking, too much.

It’s been encouraging in recent years how so many people are becoming genuinely concerned about the way the pace of city centre development is jeopardising the context and integrity of the packed area of human activity within Manchester's inner ring roads. Bodies such as Adam Prince’s Manchester Shield might not be to everybody’s taste in the way they articulate protest but that protest is delivered with just as much sincerity as Gary Neville displays.

Neville’s consortium and its proposals for St Michael’s are the latest to create concern and even outrage amongst some lovers of the city centre. People object to the destruction of the existing buildings on the site, the former Bootle Police Station and the Abercromby pub. They wonder why it isn’t beyond the wit of man to redevelop around these buildings especially the historically significant site of the Abercromby pub.

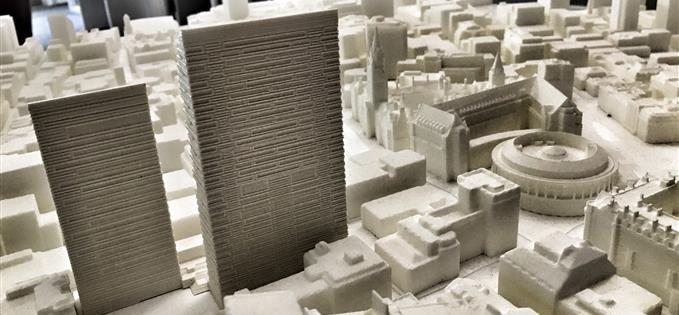

The scale of the proposed towers on the site, 31 and 21 storeys, is another problem. Historic England, the national overseer of heritage, has said the development, ‘would cause a high level of harm to both the conservation area and the setting of the nationally important civic buildings of the Town Hall and Central Library.’

Bootle Street police HQ is to be demolished

Bootle Street police HQ is to be demolished Town Hall and Central Library (right) swamped by the two new towers

Town Hall and Central Library (right) swamped by the two new towersNeville thinks the opposition is overstated.

“I think the response has probably been 80% positive while the negative response comes from a very loud 20%. We, as developer, have to balance so many things; how the proposal looks, how the investment stacks up. But listen, this is my city, so we also look very hard at the requirements of the existing stakeholders on the site; the synagogue, the pub, and consider the wider concerns and interests of the city council, plus the people who live in and visit the city. We know you very rarely please everybody.

“Historic England,” he continues, “looks at the impact on the site and we’ve taken on board some of their ideas over connectivity. But we look at the impact and also the benefit. This site currently provides ten jobs, in the pub, and when our scheme is finished it will have more than a thousand. That’s not marketing speak, that’s a fact. The economic benefit to the city from that one and a half acres is next to nothing at present. When St Michael’s is finished it’ll be vast.”

“You always have to weigh up the benefits with the harm. As a developer, who lives in the city, I have to be comfortable in my own mind that what we are putting there is better than what we have already and that it delivers a good return for the investors and for the citizens.”

“Let’s talk about the pub,” I interject. I press him on whether he realises the historic importance of the site. How the two walls against Bootle Street witnessed a key moment in the path to modern British democracy as the Peterloo Massacre swept around it in 1819. How fifteen people died in that massacre and how tradition has it one of the victims died in the Abercromby. I remind him how only the Abercromby and the Friend’s Meeting House wall up the road remain as physical reminders of Peterloo. Surely he could incorporate the pub as the lovely little 'local' for the scheme and make everybody happy?

It seems such historical nuances escape Neville.

The fact of Peterloo is not mentioned in his answer, despite my repeated emphasis, maybe I broke into Medieval Latin while phrasing it. Instead he says: ‘Within the current plan and the process we’ve been through the pub will have to come down. It doesn’t fit with how we want to improve the area. Listen I am protective of Mancunian jobs and so to take away the ten jobs would be ridiculous. Can’t happen. So they’ll be guaranteed in the new scheme. The bar of the pub is important, so we’re going to preserve that and put it in a new unit. The activity, the economic activity and the attractiveness of the new architecture will more than make up for the loss.”

The retention of the bar intrigues because it can’t be more that forty or fifty years old, so to save that and not the actual building seems ridiculous. Why bother? Raising the bar, in this instance, an absurd gesture. Neville brushes that aside as he’s been told the bar is important, and he’s prepared to make a concession to conservation with it.

How the two new towers will look

How the two new towers will look The doomed synagogue

The doomed synagogueUltimately the bigger row looks set to be over the scale of the 31 and 21 storey towers, because as I point out in the interview, these are neither slender nor unobtrusive but bulky and black.

“First,” says Neville, “I wanted public spaces, the massing of the first drawings was far too dense. Now, we propose that roughly 50% of the site will be developed as public space and we think great destinations for visitors to the site whether from Manchester or elsewhere. For me that was critically important.

“As for the buildings, twenty and thirty stories is about where it is in Manchester at present. You’ve written you want more tall buildings and this is part of that. I understand what Historic England have said but you must remember they are one stakeholder among 30-40 stakeholders.”

“But,” I say, “you must be aware these heavy black towers will overshadow the Town Hall and Central Library – the highest will perhaps be a third higher than the Town Hall spire? Most of the new tall buildings that are being delivered are being constructed in that belt around the city centre and into Salford that was hollowed out in the decades from the sixties onwards.

"In other words, they are being built on already cleared ground. Your development will literally put Albert Square in the shade at certain moments of the day. Developments surely must have regard for their neighbours, they must preserve sightlines in historic centres not ruin them?”

“Ruin the sightlines?” says Neville. “Walk up Bootle Street and Jackson’s Row and tell me where you can see Albert Square or the Town Hall? You have to turn the corner at the top and then right into the Square. How many times when wandering the streets in the city centre do you get a clear view of Albert Square or the Town Hall from ground level? Where are the people in the sky that are floating above and living there, whose view we are blocking? When I’m in St Ann’s Square, or at Kendals (House of Fraser), I just see narrow streets. It’s the way the city has been built. Meanwhile from a distance coming in from Bury or Salford the view is changing all the time with the towers that have already been given permission.”

People look at footballers and think they can be the answer to everything, it’s unrealistic

We argue the toss to and fro but in truth this is not Neville’s problem. It is the city’s. Manchester, as with Salford, has no tall buildings policy, each case is judged on its merits and while the location of the development is considered, so are several other factors.

As Sam Wallis, head of the Manchester office of GIA, told the MEN: “Tall buildings need to work well together, and there is a danger of losing the impact of existing buildings in Manchester, and affecting the character of conservation. A lack of clear policy leads to a disjointed skyline and damages views of the city. In London they have a London View Management Framework which explains how you get towers to work with existing buildings – in Manchester we don’t.”

Historically there is precedent for this, there always is a historical precedent.

Manchester and Salford for two hundred years has had a disjointed skyline because the skyline has never been considered as important. This can be seen with the construction of Highland House (now a Premier Inn) in 1966 when it was built over the River Irwell in Salford but still ludicrously close to Manchester Cathedral. Indeed the distance from Highland House to the Cathedral is the same as from St Michael’s to the Town Hall, but St Michael’s main tower is eight storeys higher than Highland House.

Maybe it’s time this inherited laissez-faire attitude of Manchester and Salford needs to be ditched. Maybe, in the 21st century, in conservation areas especially, we should think deeper about context and not rush into economic development no matter the pedigree of designers such as Ken Shuttleworth of Make Architects.

"I don't want to be remembered as just Gary Neville, ex-United and England player."

"I don't want to be remembered as just Gary Neville, ex-United and England player."Back to Gary Neville. You can’t help liking him and his drive. You can’t help admiring the way, unlike so many British footballers, he seems concerned to give something back to his city and be actively engaged in that process, to lead it. It’d be much easier to get financial wizards to push his money into some distant sunshine scheme.

Neville thinks this unfair on his ex-colleagues while conceding more should be involved with their own towns and cities. “There are footballers who do put money back into their own areas and there are many who don't,” he says. “Perhaps there should be more but then you could say that about every profession, lawyers, bankers and the rest. People look at footballers and think they can be the answer to everything, it’s unrealistic.”

As I’m leaving I look around his comfortable flat above his offices in Knott Mill and say: “What strikes me as odd, Gary, is there are no United medals on display, no pictures of you holding up the European Cup and no England caps hanging off the walls? That’s very unusual for an ex-footballer.”

He nearly froths at the mouth.

“But that’s just it. I’m not interested. There’s none of that in any of my houses, it's in storage. I don’t want to be remembered as just Gary Neville, ex-United and England player. In some ways I’m more proud of being the coach of Valencia who got sacked because I was trying something new. I don’t want to be stuck in the past. I want to be known for doing other things, for making other things happen. I still do the football punditry but I want to go way beyond that as there is so much more to achieve.”

Such as big obtrusive towers, some might say.

Big developments divide people. St Michael’s towers, from a Confidential point of view, built elsewhere, off Trinity Way or Mayfield, would be just dandy. Close to the Town Hall they appear overwhelming, brutal and destroy a rare remaining vestige of a truly portentous British event. Others with opinions seem to dislike all big towers for Manchester, or refuse to accept that sometimes older structures might have to go because they are simply not good enough to deserve reprieve. Occasionally development debates appear political, a collision of opposites, those who believe economic development is good at all costs versus those who treat it as a graphic example of aggressive capitalism and must be challenged automatically.

Such extremes are ridiculous. The reason for the interview with Neville is that Confidential was initially barred from attending the launch of St Michael’s. Neville knew nothing about this and said it wasn’t his decision, and thus personally rang me up to offer the interview rather than have this PR disaster cloud the birth of his big new baby. That’s as it should be of course, 'being open' as he repeated during the interview.

Next for St Michael’s there'll be three months with a consultation period leading to potential planning permission. There is still a long way to go, a lot to be chewed over. If you are worried about St Michael's or if you adore it, seek out the consultation and make your voice heard. Gary Neville won't mind.

Powered by Wakelet

Powered by Wakelet