Few works of fiction have become as engrained into popular culture as Anthony Burgess’ 1962 work ‘A Clockwork Orange’, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. This accolade is applied too frivolously to popular literary works but with regards to the Mancunian's most famous novel there can be no doubt as to its influence.

In many ways Alex’s statement in the novel that ‘what I do, I do because I like to do’ encapsulates the mindset of contemporary society.

Musicians as world famous as The Ramones, David Bowie, Green Day and Mötley Crüe have all taken inspiration from the exploits of Alex and his droogs.

Pop Art pioneer Andy Warhol re-configured the work for his 1965 experimental film ‘Vinyl’ and one of several theatrical productions of the book had music penned by Bono and The Edge (this version was dubbed ‘A Clockwork Lemon’ by its many, many detractors).

Then, of course, there is Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 masterpiece. Regarded as a classic by film critics the world over and arguably as responsible for the work’s resonance throughout Western culture as the novel itself.

To mark a half century of the innovative publication curators from The International Anthony Burgess Foundation (IABF) in collaboration with the Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of Arts, London are holding an exhibition at The John Rylands Library.

Retrospectively it is hard to separate the novel from the film in terms of their impact. Undoubtedly the success of the film has played a large part in keeping the work at the forefront of popular consciousness.

Due to the accessible nature of film it’s increasingly the case that people will have their interest piqued by on screen adaptations and be motivated to delve into the original source material. Other notable examples of this trend include Terry Gilliam’s ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ and Danny Boyle’s ‘Trainspotting’.

The ramifications this has in a time when Hollywood is scraping the fairy tale barrel for sources are worrying but in the case of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ both the novel and Kubrick’s film are powerful cultural artifacts. If you hold the belief that commercial films can be art then Kubrick’s stunning adaptation is surely deserving of that distinction.

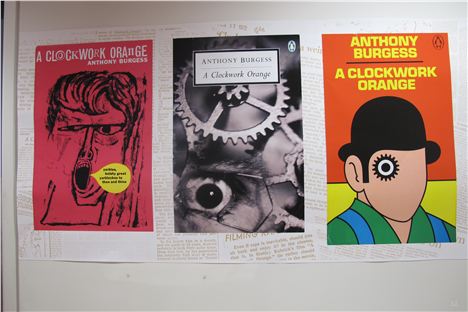

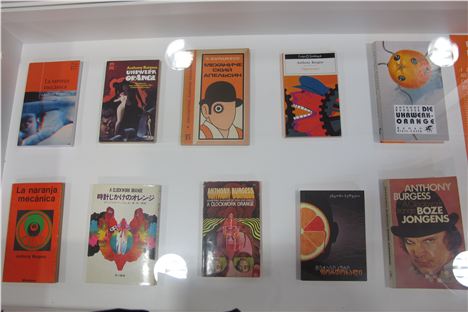

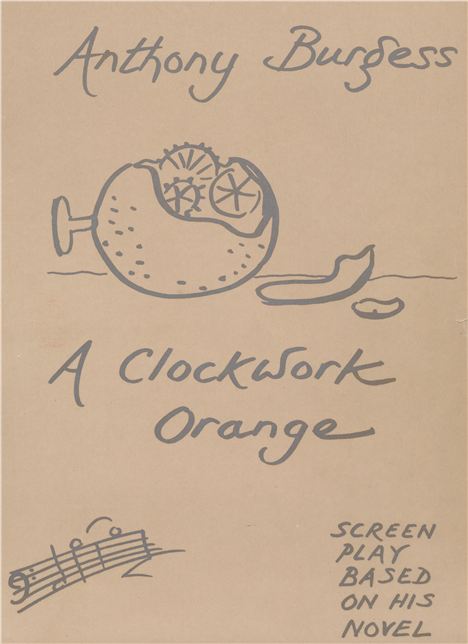

Appropriately, this new exhibition will analyse the ways in which the novel has expanded beyond the pages of Burgess’ text, examining the text’s various manifestations over its fifty year lifespan. Rare books, manuscripts, photographs, film props and a cornucopia of other elements converge to present a coherent picture of ‘A Clockwork Orange’.

In the International Anthony Burgess Foundation on Cambridge Street there is a selection of material which gives a taste of what to expect when the exhibition opens. Highlights are the letters to and from Burgess which hint at his complicated relationship with the film.

Although he was pleased with the final outcome of Kubrick’s work one section gives particular insight into the author’s mind and his grievances with the film: ‘It’s something to do with the book being merely one item in the whole panoply of film-making, like hair dressing and chief grip. There are odd people trying to boss me around. But I have Liana and Andrea (wife and son) and the micrographed OED (complete with magnifying glass) and what else do I need?’

One crucial factor that divides the film from the novel is the effect of time on the two works. Even the most passionate defender of Kubrick’s film would have to concede that his work hasn’t aged particularly well. The novel, on the other hand, still seems relevant, exciting and important in a way that is rare for radical dystopian fictions.

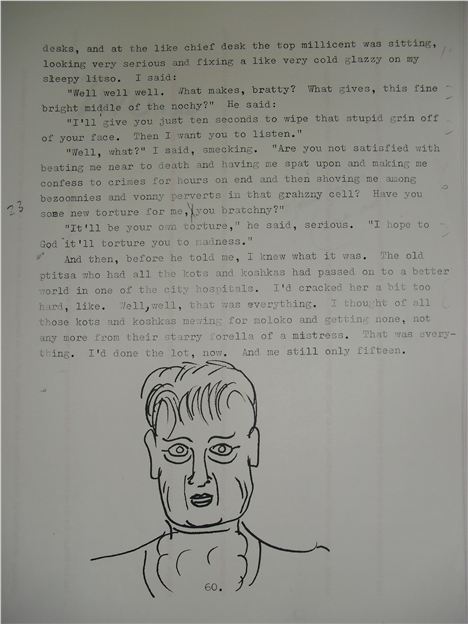

Anthony Burgess' sketch of Alex under some original text

Anthony Burgess' sketch of Alex under some original text

The vitality of the book is a testament to Burgess’ prescience and vision. Last year’s riots, the profusion of drugs like bath salts with their incitement to violence and the recent prosecution of feminist Russian punk band Pussy Riot for 'hooliganism' all indicate that the problems Burgess addressed in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ are still valid and important issues for debate.

In many ways Alex’s statement in the novel that ‘what I do, I do because I like to do’ encapsulates the mindset of contemporary society. #YOLO in Twitter terms.

In closing here are deputy director at the IABF Will Carr’s thoughts: "A Clockwork Orange is a key text about youth culture, dystopia and the role of the state and it’s not going to go away. Its appeal is ensured."

The exhibition, which runs from the 21st of August to the 27th of January, will be open daily and entry is free. More information here. Follow Alex on Twitter @AlH_HlA