Jonathan Schofield appreciates the bold beauty of a new bridge on a controversial site

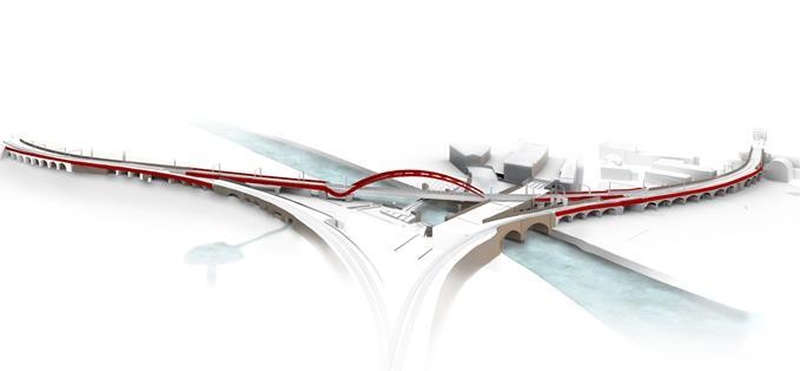

PETER JENKINS is a proud man and he should be. He’s the engineer who designed the graceful sweep of the new Ordsall Chord bridge over the River Irwell which was lifted into position in late February.

The steel element incorporating the bridge resembles a single elegant pen stroke from Japanese calligraphy

“Most buildings we design have an insurance life of around 25 years,” says the BDP man, “but Network Rail wanted 120 years for this bridge. I like that sense of permanence.”

I point out 120 years is almost five generations and if we take that back in time rather than forward we’d be discussing a bridge from 1897. Tour guides and reference books would now be referencing Peter Jenkins’ name. As they will in 2037. I envy Jenkins' posthumous legacy. I envy that permanent marker he has placed on Manchester.

Jenkins joins some mighty personalities in throwing bridges over the River Irwell and its extension, the Manchester Ship Canal. He sits with the lofty company of James Brindley (designer of the original Barton Aqueduct - now demolished), George Stephenson (the Liverpool & Manchester Railway viaduct), Jesse Hartley (Albert Bridge), James Gascoigne Lynde (Irwell Street Bridge), Edward Leader Williams (Barton Swing Aqueduct and Irlam High Level Viaduct), Santiago Calatrava (Trinity Bridge), Wilkinson Eyre (MediaCity swing bridge). We'll be doing a Best of Irwell Bridges soon so look out for profiles of all these fines structures.

Jenkins' bridge is only part of the whole Ordsall Chord scheme, 89m out of more than 320m, but it is the defining moment.

The steel element incorporating the bridge resembles a single elegant pen stroke from Japanese calligraphy. It combines adventure with subtlety as the Cor-ten steel section narrows from Salford over the river into Manchester.

“On the Salford side it’s three metres,” says Jenkins of the steel platform under the bow of the bridge. “It then reduces to two metres and eventually half a metre on the Manchester bank. This helps lighten the bridge visually as it nears the Grade 1 listed George Stephenson 1830 viaduct for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (LMR).”

Technically the bridge is an ‘asymmetric network arch’, which deals with the problem of the structural challenges of trains curving across the bridge and not moving over in a straight line.

The design is a triumph and will allow us to view Stephenson’s viaduct clearly for the first time in over a century. Stephenson’s bridge is formed of two sweet segmental arches (these are arches less than a full half-circle) leaping the river and made from big beefy squared off and smoothed sandstone blocks. The design is efficient, smart, and because of that simple fitness for purpose, beautiful, in how it looks and what it does. It’s cleverly slewed at an angle across the river.

The nature and grace of the two structures is different but they both bring an aesthetic quality to civil engineering.

The view of the older structure will be assisted by the construction of a new footbridge under the Ordsall Chord rail bridge. “That was a real team effort,” says Jenkins, “involving BDP, WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff, DM&W, AECOM, Mott MacDonald.” Complex and unlikely to be much repeated by tour guides as they explain the footbridge.

The area around the new bridge and footbridge will be given a high quality landscape treatment which will provide a foil for the £110m performance space, The Factory, from Rem Koolhaas’ OMA.

The landscaping is a bonus throughout the Ordsall Chord scheme.

One particularly engaging element will be close by The Factory, under the Water Street viaduct at the back of the Museum of Science and Industry (MSIM). The original Stephenson bridge here was a technical marvel of its time using iron and the pioneering Hodgkinson beam from William Fairbairn’s Works in Ardwick. Its columns, apparently, gave it the appearance of a classical temple. It was lost in 1904 as the road was widened. With the Ordsall Chord landscaping the former columns will be marked by bases placed in the pavement while directly above lights will shine down. Thus the old columns will become ethereal and formed from light.

A railway arch to the south will be paved and provided with street furniture. This will frame the oldest passenger railway station in the world, the terminus of the aforementioned LMR, now part of museum. This area also reveals how the older brick arches have been wrapped by the new concrete elements to provide a wider track area above. The concrete here is provided with a sweet arcade made of 'transverse arches' at right angles to the rail track. The concrete is canted back and faced with more Cor-ten steel to add to the visual effect of the rhythmic march of the arches.

What impresses most about the works associated with the Ordsall Chord is the sheer ambition of the project, its vigour. There are several huge compounds around the site, where materials and equipment is hired and which are alive with construction workers. The canteen is huge. At one point over Christmas more than 1,500 people were on site.

The scale reflects the boldness of the pioneers who worked on projects such as the LMR and later on the Manchester Ship Canal. The workers' compounds for the Ordsall Chord don't have pubs or brothels like the ones that grew around the 1880s-1890s workings of the Manchester Ship Canal. Health & Safety gone mad.

Of course, Manchester Confidential should hate the Ordsall Chord. Regular readers might have been hissing as they read the paragraphs above, calling us hypocrites because in article after article we criticised the project.

You see, for all the grandeur and boldness of the Ordsall Chord there is a tinge of regret that the epoch-making original link between Manchester and Liverpool where the Railway Age began, has been broken. As we wrote in September 2015: 'The proposed route linking Manchester’s Piccadilly and Victoria Stations will castrate the oldest passenger rail line in the world, cutting off the station from the rail network. To lose the integrity of such powerful heritage and the potentially huge future tourist benefits seems perverse. Andrew Davison, former boss of English Heritage, has called this site “the Stonehenge of the Railways”, and said: “This is the place where the modern world began."'

In the end the heritage merits of maintaining the original line rather than cutting it for the Chord were found to ‘not outweigh the public good'. At Confidential we still believe that was a decision to be regretted, yet now we have compensation. The verve, effort and money Network Rail and their partners have put into the project must be applauded and celebrated. They were no doubt encouraged to do things properly by the row that the line-breaking caused.

The Ordsall Chord will see Manchester’s three main stations, Victoria, Oxford Road and Piccadilly, linked via heavy rail for the first time, increasing capacity and easing congestion at the latter by an estimated 25%. There will be more frequent services through the city, and more direct links across northern cities, opening new routes directly to Manchester Airport from locations including Newcastle, Bradford and Rochdale. Up to 30,000 extra jobs might be created, although this perhaps needs referral to the Dubious Statistics Panel.

What is a fact is that Jenkins’ swish of Japanese calligraphy over the river has given excitement to this end of the city centre. It has given it potency and grace too. "I wanted something that added to the city with an architectural quality as well as being functional and efficient," says Jenkins.

He's succeeded.