In 1989, a Liverpool-born music journalist was contacted by Paul McCartney's office in London

and invited to interview the star.

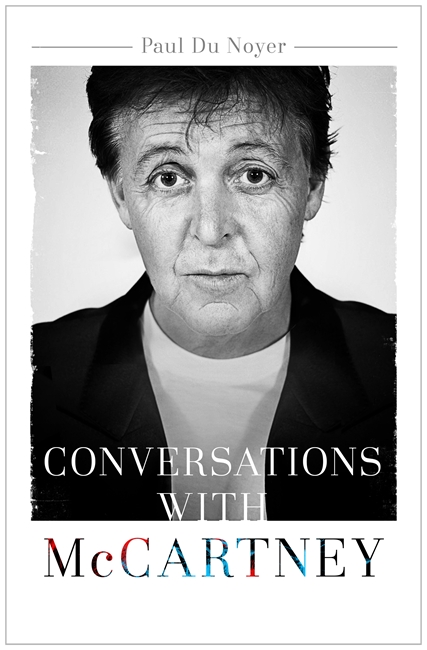

They had met before and enjoyed a good rapport. In the years that followed, Paul Du Noyer (right) continued to meet, interview and work closely with McCartney, their conversations moving between music – life as one of the Beatles and later with Wings – and his most private feelings on John Lennon and his beloved Linda, among others.

Over the last 35 years Du Noyer has interviewed McCartney more often than any other magazine

writer. Conversations with McCartney is the result. Drawing from their interview sessions and coupling McCartney’s own candid thoughts with Du Noyer’s observations, the book is an intimate portrait

spanning McCartney’s entire musical career.

You can meet the author tomorrow night (Wednesday, September 23, 7.30pm, £6) at Leaf, Bold Street, in a Q&A with MIke Neary organised by Waterstones.

But for now, read on. For diehard Macca/Beatles fans, we will be publishing an interview from the book later this week. Get the kettle on.

By Paul Du Noyer

THE nearest I have come to dying, so far, was an asthma attack in childhood. I found myself in a Liverpool hospital with an oxygen mask clamped to my face and radio headphones on my ears. The station was broadcasting the Beatles’ new record Abbey Road in its entirety. That is why, when people call the group’s music ‘life-affirming’, I understand them in a very literal way. At that moment, I suddenly realised how much I loved them, and how much I wanted to live.

That was in 1969. Whereupon, of course, the bastards split up.

I forgave them, naturally, and followed all their solo careers with rapt attention. I grew up and became a music journalist, with the good luck to interview Paul McCartney on many occasions. John Lennon died before I ever had a chance to meet him, which is my biggest professional regret. But Paul and I seemed to hit it off.

That is how this book came about. I have drawn together our scattered conversations from each of those encounters, and re-ordered them into a single narrative. From it emerges, I hope, the story of McCartney the musician, told in his own words with a few of mine as well. His long career has produced a stupendous body of work that rewards listeners at every turn.

The Beatles attained a state of pop perfection very early on. After that, they did what seemed incredible, by revealing with each new record a new and completely different type of perfection. It couldn’t last forever and it didn’t. But Paul, like John Lennon, was expected to perform the impossible again and again, or else be held to the cruellest of accounts

His position is unparalleled, whether we measure it in commercial success, artistic achievement, or his influence on others. In terms of posterity, his reputation will ultimately be unassailable. I’d also contend that McCartney’s music, sometimes assailed by critics as safe and bland, is more often questing and downright strange.

Since he joined John Lennon’s band the Quarrymen in 1957, Paul has scarcely paused for breath. He’ll write a timeless love song with the same ease that other people draw breath. He’ll play rock and roll with more raw sex and aggression than you tend to encounter outside of penal institutions. The Queen of England thinks he’s marvellous, but even the edgiest avant-garde types admit that his music can take a walk on the weird side. From kiddie-pop to classical, there is hardly a genre that he hasn’t tried; probably only Picasso could rival Paul McCartney’s claim to stylistic breadth.

It’s actually very hard to have a hit record. To keep on having them is practically impossible. For all his peaks and troughs, McCartney’s career rivals that of any contender we might nominate. The crumbs from his table would be the pride of lesser songwriters. The glory of show business is that it gives the people what they want. The glory of art is that it gives us what we never knew we wanted. And the glory of Paul McCartney is that he does both.

Have the results been consistently wonderful? Not at all. But when his star is in the ascendant there is no composer in the whole of popular music to match this man’s ability to write the songs that make the whole world sing.

The Beatles attained a state of pop perfection very early on. After that, they did what seemed incredible, by revealing with each new record a new and completely different type of perfection. It couldn’t last forever and it didn’t. But Paul, like John Lennon, was expected to perform the impossible again and again, or else be held to the cruellest of accounts.

Paul, it was allowed, had a craftsman’s facility that could glide from manic to manicured. But his soul, it was said, was still in show business. While his achievements as a Beatle made him a hip figurehead of the new rock culture they had helped to create, his heart could not abandon the occasional nursery rhyme or treat for the mums and dads.

A shameless crowd-pleaser, then? The stereotype has a nugget of truth, insofar as he never saw a reason to limit his musical palette. But it does him a grave disservice in suggesting that he was a lesser artist by virtue of his versatility. If you were feeling poetical you could say McCartney’s work is like an oak tree: the trunk is strong and broad but its branches spread and twist in fantastical patterns.

He wisely shies away from this analogy, but Picasso’s transcendence of category, his sure grasp of traditional skills with an appetite for the new and untried, are things McCartney admires. And by now there is also the sheer

enormity of his output, a tribute to both his energy and longevity. McCartney’s music has not developed in any one direction over time. Instead it resembles a kind of unwinding spiral, achieving an ever-wider circumference.

Born on 18 June 1942, Paul McCartney emerged before the days of rock and roll; he was formed in a world which has utterly vanished now, and which was hastened on its way by the Beatles themselves. He came of age in the aftermath of the Second World War, one of the biggest disruptions in human history. All minds were now fixed on a modern world, and the less it resembled the past, the better. Nothing could be learned by looking backward. Or so it felt at the time.

Paul could be every inch the teenage rebel that his generation specialised in producing. But he was never, in his heart, an iconoclast. That’s a contradiction that has persisted throughout his music, and it’s the source of some critics’ contempt for what he did. But it’s really one key to his greatness. He’s among the last of that dwindling number who were not fundamentally shaped by rock, because they already had some musical understanding before it reached their ears.

But this book is not all about the Beatles. I once mentioned to McCartney how writers tend to compress the decades of his life after 1970 into a desultory postscript. Paul replied:

Now you mention it, you can see it. I’ve met enough journalists, having to get articles that are winners, to know the game. ‘He was a Beatle.’ That’s basically the game. Any book on John Lennon they do the same. They condense the Yoko period: ‘Oh yeah, peace chants, they wore funny hats and sunglasses, and he was militant, wasn’t he?’ It compresses fairly easily.

But I like it in a way – it’s the same about music that I’ve written in that period – because I think it’s undiscovered. It’s really been blanked: ‘No, he didn’t write anything since the Beatles.’

Once you start to look . . . I mean, commercially there definitely are things that outsold anything the Beatles did, like ‘Mull of Kintyre’. But critically I don’t think people would consider that. Although an awful lot of people liked it, so who am I?

It’s not that he’s embarrassed by the Beatles, even if their legacy dogged his early solo years. In all my interviews I found he’d bring them up more often than I did:

I used to say to my kids, ‘You’re the only ones who never ask me about the Beatles!’ I used to wish their friends would come round and say, ‘What was it like being in the Beatles?’ ‘Well, let me tell you . . .’ And the kids would all go out the room: ‘Oh bloody hell . . .’

That’s how kids are, they don’t want to hear about that shit, but their friends would. So I’d chunter on [cheerful windbag]: ‘Oh! It’s funny you should say that!’ An hour later . . .

The trap is that the Beatles make us skimp the great music he’s made in his forty-five solo years. In this book I want to correct that imbalance. Paul said to me that his career will one day be seen in its totality. I’d like to think that day has arrived.

The richness and diversity of McCartney’s solo work, from that infamous chorus of frogs to his most esoteric electronica, needs to be recognised. The beauty of his back catalogue is in its endless variations and surprises. The devil may be in the detail, but in McCartney’s case we find our angels there as well.

His own repertoire runs into many hundreds of songs. We all know that he wrote ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘Hey Jude’. We should acknowledge that after that came lesser-known beauties that will, in the end, outlive us all. McCartney’s post-Beatle material is a curiously under-valued treasure trove of pop history. He agrees:

That’s my theory, that in years to come, people may actually look at all my work rather than the context of it following the Beatles. That’s the danger, as it came from ‘Here There and Everywhere’, ‘Yesterday’, ‘Fool on the Hill’, to ‘Bip Bop’ [from Wings’ Wild Life], which is such an inconsequential little song. I must say, I’ve always hated that song.

I think there will be an element of that in time to come. And with John’s work too. They’ll look at it in greater detail and think, Ah, I see what he was getting at. Because it’s not obvious, that’s the good thing. It’s a bit more subtle than some of the stuff we’ve done, which was out-and-out commercial. But I think it’ll look more and more normal as time goes on.

Though I’ve rearranged the sequences, the earliest interview in this book dates from 1979, when I was sent to a backstage press conference before a Paul McCartney Liverpool concert. It was a dream assignment, and the moment I realised I had stumbled into the right career. If the book is not so much a biography as a portrait, it’s at least a portrait taken from life. With a couple of cited exceptions, every McCartney quote you’ll read here is first-hand.

I met Paul regularly when I was a journalist on magazines such as NME, Q, MOJO and The Word. I also helped him on editorial projects including tour brochures, press kits and album liner notes. Our focus was always on the music, though not in a narrow or technical way; in talking of his songs he’d share many memories, and describe the personal joys and sorrows he had felt along the way. There are certainly gaps in the narrative that follows, because we always had particular topics to cover. But he talked freely about every stage of his career.

Part One of this book is roughly chronological, and Part Two is more thematic. In real life his conversation is liable to roam back and forth, and I have ‘remixed’ our interviews to improve continuity. In all, across those thirty years and more, he vividly described for me the whole business of being Paul McCartney.

It helped that I was from Liverpool. We both began our lives in Anfield, the district of terraced streets around the famous football ground; then we moved out to identical houses on opposite sides of the city. Twelve years apart, we’d attended similar schools. We would sometimes digress and discuss bus routes, docks and department stores in absurd detail. But in his own mind he never became the superstar he became in everyone else’s. He hates to look remote, or grand, and he always took pains to make our interviews feel like conversations. I don’t pretend to be his friend, but our encounters were friendly. I saw at close range the crushing demands on his time and attention. He bore it all with remarkable patience, including my incessant questions. I came away with the idea that Paul McCartney is a decent guy, who happens to be a genius.

*Conversations With McCartney (£25, Hodder and Stoughton) is published this Thursday, September 24, in ebook and hardback.