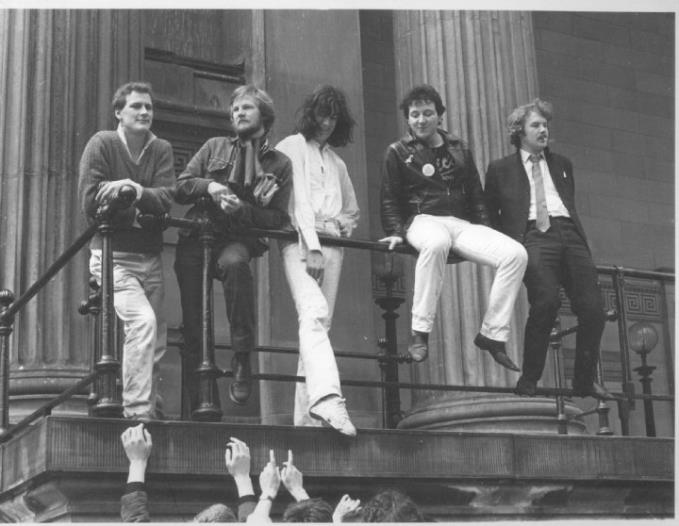

THOSE with elephantine memories - or an interest in Liverpool’s illustrious rock family tree - will recognise Peter Hart as the frontman of late 1970s city punk band Those Naughty Lumps.

The student group were famous, almost, for recording a track called Iggy Pop’s Jacket on the Zoo Records label.

"Lumps" is not the best word for a chef to be associated with, nevertheless bassist was Martin “Armadillo” Cooper who these days can be found running Delifonseca Dockside's kitchen. If that isn’t starry enough for you, the band's manager is now the watchdog of the nation’s prisons.

However it is those with far longer memories to whom Hart has dedicated his entire professional life. Memories that stretch right back to the First World War.

Then

Then

Now (Peter Hart, second left)

Now (Peter Hart, second left)In 1981, at the age of 26, Hart laid down one microphone and picked up another that would have far reaching consequences. The long-haired Liverpool University graduate got a proper job: oral historian for the Imperial War Museum. It meant interviewing, on tape, hundreds of veterans of the Great War, soldiers, sailors and airmen, officers and privates alike.

Every one of these survivors is now, of course, dead, but thanks to Hart and that timely 1980s work, their recollections form a major national archive so the world might never forget.

It's tens of thousands of hours listening and now a selection of these first hand accounts has been transcribed in book form: Voices From The Front: An Oral History of the Great War, published by Profile.

It is a weighty, authoritative, master work from the mouths of men nearing the ends of their lives, reaching back into the furthest portals of recall. Anecdote after anecdote of pain and suffering, hope and fear, tragedy, comedy and all of human nature is illustrated against the backdrop of “the war to end all wars”.

Hart talked to Tommys who saw their friends die in front of them, who were seriously wounded themselves, men who refused to fight on principle and those whose spirit propelled them through thick and thin.

He told Liverpool Confidential: “These were brave men who could take all their enemies could throw at them and ask for more; nervous types who had to dig deep. Many got through without a scratch, but some were dreadfully wounded, their lives ruined or changed forever. Few had ever written anything down or preserved their letters.

“Sometimes they were there at crucial turning points in the war - going over the top in the slaughter of the Somme in 1916 or punching through the German lines to victory in 1918. Others sweated and toiled on a forgotten front, thousands of miles from home.”

Hart was recently described as “at the peak of his powers” by the distinguished Great War chronicler and film maker Richard Van Emden - and the accolade is plastered across the jacket of his book.

Hart describes his interviewees as everything from “Quiet bespectacled types, rough diamonds and solid bible reading types, to intellectuals, eccentrics, even a few who still 'liked a drink'."

This, of course, could as easily describe the one time following enjoyed by Those Naughty Lumps.

Back in the day they were one of the top new wave Liverpool bands and Julian Cope and Bill Drummond both appear on the frivolous and aforementioned Iggy Pop’s Jacket.

"Despite all of our opportunities, we never quite made it," says Hart, "and in 1980 we broke up and moved away to take up real lives."

But you can't go to your musical grave on that note, so 36 years on the Lumps have not only reformed with original stalwarts Kevin Wilkinson and Max Factor but have put out their first album: Not Quite Ten.

Recorded at Liverpool's Vulcan Studios, it is a wry, clever and witty collection of tracks (hear Iggy in its full original glory) and is being launched in Liverpool with a party, this Saturday (November 14), at Fogherty's, off Smithdwon Road.

Their manager was Frances Crook – now director of the Howard League of Penal Reform. Whether she or any other connected luminaries will show up to the launch remains to be seen. What is guaranteed, if their last gig in Liverpool is anything to go by, is a fun filled night of droll performance and banter. They've still got it.

*Those Naughty Lumps, Foghertys, Blenheim Road, off Smithdown Road, Liverpool Liverpool on 14 November.

* Voices From The Front: An Oral History of the Great War, published by Profile. Cover price £25.

Book extract....

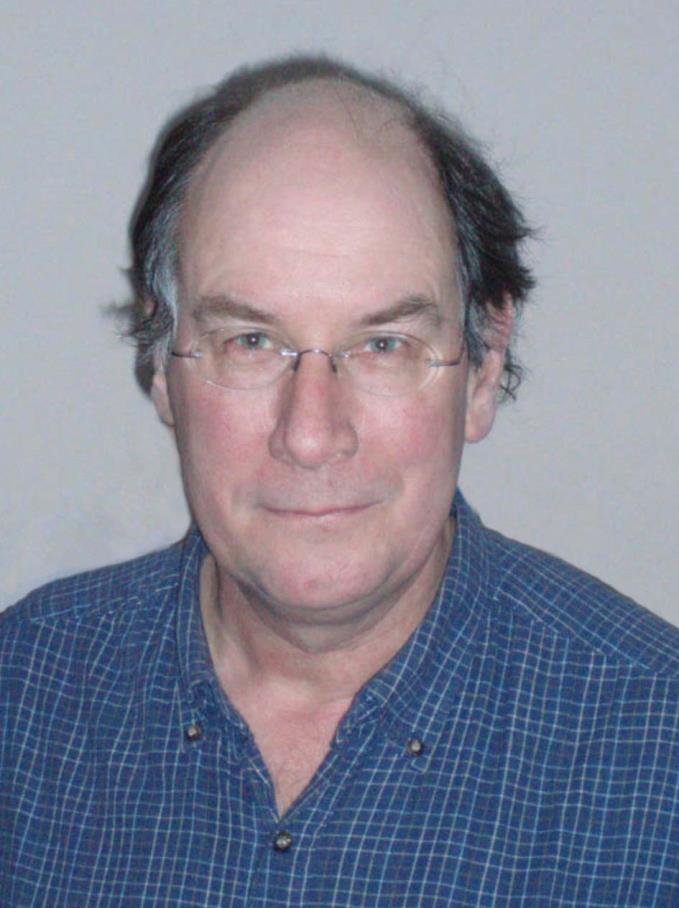

Peter Hart (pictured, right) told Liverpool Confidential: "I’m most proud of the Joe Murray interview, a man from Burnopfield in Co Durham. He had total recall and although blind recorded some 22 hours of tape recordings in 1984. – He was about 88 then – I was 29. Alert: The dysentery quotes are particularly raw."

MANY working class lads from poorer backgrounds were under-nourished and the combination of PT, an improved diet and fresh

air generally worked wonders on their overall physical condition.

Yet some of them harboured the deepest suspicions as to the motivation of their instructors.

We had a Leading Seaman Harris! Oooh a proper swine, really a swine! We used to go out route marching and drilling, "Right turn, left turn! Advance, fix bayonets! Keep your rifle at the port!" And every time we came to some mud, "Lie Down!" Honestly and truly we got wet through. He seemed to make a point of making us lie down where it was muddy. I couldn't for the life of me understand why he was such a so and so!

Ordinary Seaman Joe Murray, Hood Battalion

The Hood Battalion was sent to Gallipoli and Murray was ordered forward in the Second Battle of Krithia on 6 May. The plan looked to the capture of Achi Baba, but the reality as the troops moved forward was a chaotic advance to contact. What happened to the Hood Battalion as they probed forward in the Achi Baba Nullah was typical. To them the Turks were completely invisible; but their bullets seemed to be everywhere.

There’s no sign of the French. It was a beautiful morning. We got to a farmhouse, what was left of them, knocked about but serviceable. We were lying alongside the corner of a vineyard, a bush hedge, 3 or 4 feet high a little ditch on the side. We started numbering. There must have been at least 50-60 men there. Then we were told to swing round behind the house and move forward. We found ourselves alongside another hedge of the vineyard. There was a big gap, about 12 feet wide, it looked like the roadway into the farm house.

We lay there for a little then we were told to bear left, we were at the junction between the French and the British and we tried to keep connection with both flanks. We kept losing so many men we couldn’t do it. We could never locate these snipers. There were no trenches; it was open fighting. We had to rush along the front of the house and go through this gap.

Only four people got through, we had to climb over the dead and the wounded. We got about 10 yards in front, and down we went. The bullets were hitting the sand, spraying us; you were spitting it out of your mouth.

Ordinary Seaman Joe Murray, Hood Battalion, 2nd Naval Brigade, RND

Murray (right) found himself with just his three companions in front of the hedge. Feeling terribly isolated and not knowing what to do, they decided to keep on trying to push forward.

I remember, Yates was just a little ahead of Don [Townshend] and I. We crawled up more or less line abreast but the bullets were hitting the sand, spraying us, hitting our packs. So we decided, "How about another dash?"

Off we went. Near enough 15 yards, one drops, everybody drops. We got down again! We decided to go a little bit further. We'd got to keep bearing to our right slightly, because we seemed to be dodging the line of fire. But it was still whinging overhead and flying about, hitting the ground. I think it must have been a machine gun.

But there's a tendency for a man, if he's being fired on by two or three men at the same time, to think it a machine gun. You couldn't see them and there was a rattling going on, not only in our section but all over the place. Rapid fire was going on. We decided to go a little bit further and all four got up together. Yates was in front and all of a sudden he bent down.

He kept crying for his mother. I can see him now. Hear him at this very moment. He said he was eighteen, but I don't think he was sixteen, never mind eighteen. He was such a frail, young laddie. He was a steward on the Fyfe banana boats in peacetime

He'd been shot in the stomach, maybe the testicles, but he was dancing around like a cat on hot bricks, fell down on the ground. We decided to ease up a little bit. But as soon as we got somewhere near him he got up and rushed like hell at the Turks and "Bang!" Down altogether, out for the count. Horton and I were more or less together.

Townshend was on the other side and there was a gap where Yates had been. Young Horton, he was the first to get to Yates and he got a hold of him and sort of pushed him to see what was wrong when a bullet struck him dead centre of the brow, went right through his head and took a bit out of my knuckle. Poor old Horton.

He kept crying for his mother. I can see him now. Hear him at this very moment. He said he was eighteen, but I don't think he was sixteen, never mind eighteen. He was such a frail, young laddie. He was a steward on the Fyfe banana boats in peacetime. Yates was dead. Horton was dead. Only Don and I left.

Ordinary Seaman Joe Murray, Hood Battalion, 2nd Naval Brigade, RND

Dysentery was a dreadful problem at Gallipoli - propagated by the complete lack of effective sanitation. It laid waste to entire units, hollowing them out from within.

With dysentery you keep on trying to discharge something but there's nothing to discharge, it's only slime, just slime, no solids at all. Then of course we didn't have any toilet paper and you had to wipe yourself with your hand, there's nothing else. Then you'd wipe your hand - originally on the grass, but grass was getting a bit short - rub your hands on the sand and your trousers.

Ordinary Seaman Joe Murray, Hood Battalion, 2nd Naval Brigade, RND

It was deeply degrading and soon even the strongest proudest specimens of manhood found themselves reduced to mere shadows of their former selves.

My old pal, a couple of weeks ago he was as smart and upright as a guardsman. After about 10 days to see him crawling about, his trousers round his feet, his backside hanging out, all soiled, his shirt - everything was soiled. He couldn't walk.

My pal got a hold of him by one arm; I got a hold him by the other. Neither he nor I were very good but we weren't like that.

It’s degrading, dragging him to the latrine, when you remember how you saw him just a little while ago.

We lower him down next to the latrine. We're trying to keep the flies off him. We were trying to turn him round put his backside in towards the trench.

I don't know what happened but he simply rolled in to this foot wide trench, half sideways, head first into this slime. We couldn't pull him out, we didn't have any strength and he couldn't help himself at all. We did eventually get him out but he was dead, he'd drowned in his own excrement.

Ordinary Seaman Joe Murray, Hood Battalion, 2nd Naval Brigade, RND.