Radical visions were more lemon squeezer than Lutyens. Did they get it right?

For anyone aged 50 or under, the Liverpool skyline has always featured the upturned concrete loudhailer that is the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King.

Designed by the prolific post-war modernist Sir Frederick Gibberd, it has served to weigh down one end of Hope Street for half a century, and it’s difficult for most of us to imagine modern Liverpool without it.

However, it’s always intriguing to get a glimpse of the what-ifs and might-have-beens that could have taken the place of any familiar landmark, and Paddy’s Teepee (it doesn’t look anything like a wigwam, as any school kid should know) might have taken a great many alternative forms.

Back in 1959, the Archdiocese of Liverpool held an architectural competition to choose a design for the site, having finally decided to abandon Sir Edwyn Lutyens’ pre-war architectural behemoth due to the immense costs involved. Coming at a time when new ways of thinking were sweeping through both the worlds of architecture and the Catholic church, it’s no surprise that a large number of the 298 entries took a non-traditional approach to the project.

Twenty three designs were eventually shortlisted, including submissions from Denys Lasdun (architect of the National Theatre), Peter Eisenman (designer of Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial) and Archigram, whose stark arrangement of forbidding concrete forms was perhaps the most uncompromising of the lot.

Gibberd’s winning design is now celebrating 50 years since its inauguration, but an exhibition called A New Cathedral 1960 is allowing those visionary near-misses to enjoy a little of the limelight too.

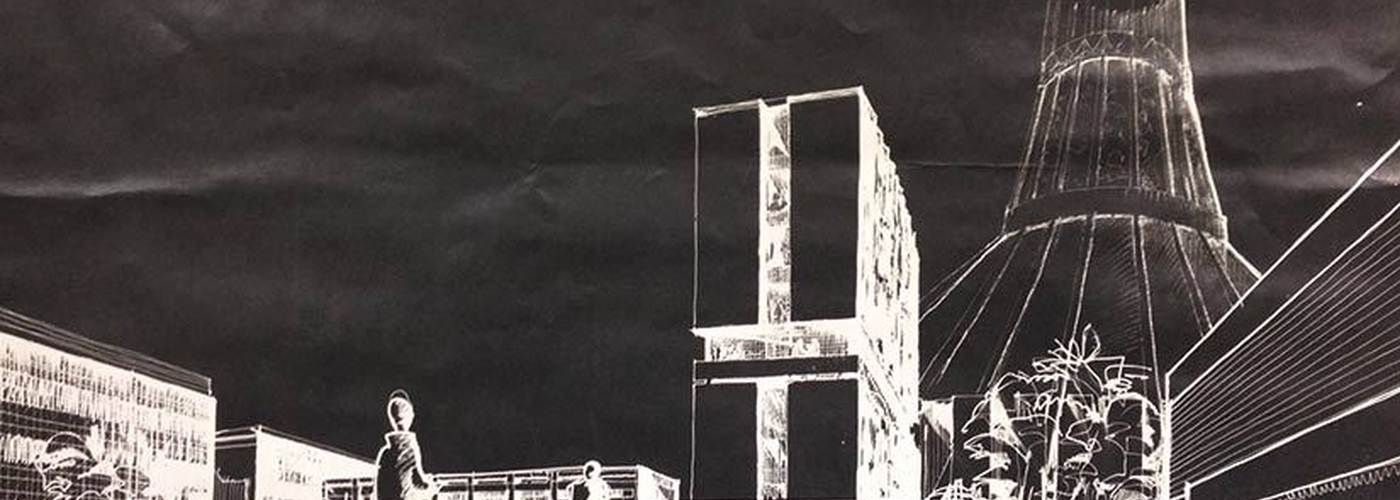

The nearest miss of them all was the spectacular entry by C.H.R. Bailey (above), who was placed second in the competition. Formed from Sydney Opera House offcuts with a tall icing-bag nozzle of a tower, the design came closer than any other to bookending the northern end of Hope Street.

Ultimately, the three judges (including Sir Basil Spence, designer of Coventry’s post-war cathedral), settled for Gibberd’s circular concept, with its centrally located altar proving particularly in keeping with the democratic spirit of the times. Perhaps the apocalyptic skies on the Bailey visualisation made things look a bit too Old Testament for a cathedral born in the Space Age.

But A New Cathedral 1960 gives us a glimpse into the world we might have had, even as the existing building settles into its second half century. Gibberd’s cathedral might now seem as if it’s always been here, but what a different looking city we would have had with Bailey’s crinkle-cut vision reaching for the sky.

*A New Cathedral 1960, Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedra, Mount Pleasant, L1. Until September 10. Free.