LIVERPOOL held a special attraction for Ken Campbell.

Ever since Peter O’Halligan informed him that Carl Gustav Jung had a dream that placed the city as the Pool of Life, Ken put most of his energies into making things happen that would live up to that sentiment.

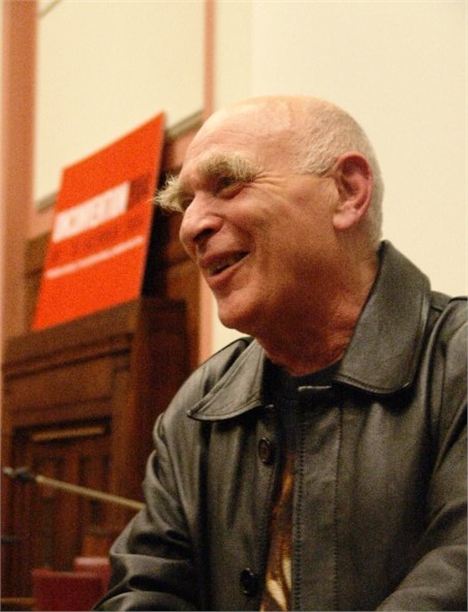

Author Jeff Merrifield has recently completed a biography of the great theatrical entrepreneur and innovator - SEEKER! Ken Campbell: His Five Amazing Lives.

Ahead of a special Q&A at Mello Mello, next weekend - where Ken Campbell made his final Liverpool appearance in 2007, Jeff looks back at some of the major moments in Ken's Liverpool escapades.

ON 23 November, 1976, the “most remarkable play staged on Planet Earth” opened in Liverpool - at the Liverpool School of Language Music Dream and Pun in Mathew Street.

It was a dramatisation of the Illuminatus! Trilogy, by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson. It was also the first production by the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool, the brainchild of theatrical maverick and innovator Ken Campbell, Chris Langham and some more actor chums.

Many people regarded Ken’s production of Illuminatus! as stupefying and astonishing. Science fiction author Brian Aldiss was one of the most outspoken champions of the sensational happenings that took place on the first of the complete cycle performances in that upper room Liverpool café parlour, colloquially known as Aunt Twackies, now Flanagan's Apple.

'Nobody, I told myself as I staggered afterwards, is going to believe this… I can’t recall ever sitting in a theatre sweating with suspense, while laughing my head off… Here is genius with a Gee!'

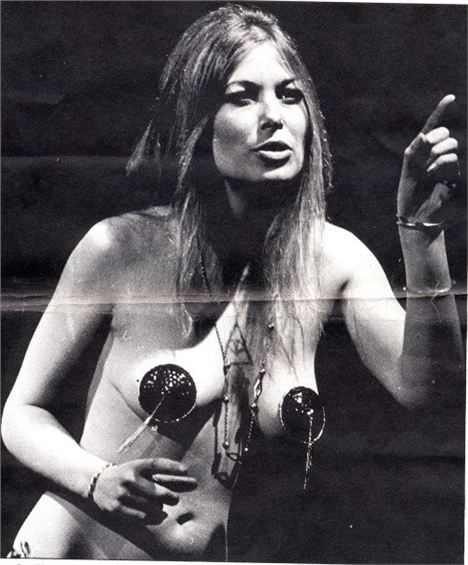

Writing in the Guardian, Aldiss, in using the descriptor “genius with a Gee!”, evoked a ringing pun on the name of Prunella Gee, who played the sexy guerrilla Discordian revolutionary, Mavis, as well as Eris, the Goddess of Discord/Chaos and was one of “many remarkable actors in a remarkable piece”

Prunella Gee, Goddess of Chaos

Prunella Gee, Goddess of Chaos

The overriding themes of Illuminatus! - described as a drug-,sex- and magic-laden trek through a number of conspiracy theories, imagined or otherwise - reflected one of Ken’s major considerations: the struggle of the underdog against the monstrous forces of misplaced totalitarianism.

Ken had struggled against the conservative forces of the theatrical establishment and carved his own place as an underdog nonconformist. This profound identification with other earnest underdogs and the sharing of an adventurous journey impressed Michael Coveney, along with many other critics.

'As we reeled out of the tiny theatre at 10.30 on Sunday night (having arrived at 9.30 on Sunday morning) and repaired once more to the Corkscrew Wine Bar (open all day for those wearing a badge proclaiming membership of the League of Dynamic Discord) we knew that if the Illuminati remained predictably unvanquished, we at least had been part of an exciting dream that was, perhaps, only just beginning…'

He went on:

'Far be it from me to describe what Illuminatus! is all about. That would be like trying to write the history of the world on the back of a postage stamp… the result is about nine hours of excitement in which anarchy is as tightly programmed as the pairing of crocodile chromosomes.'

Aldiss, meanwhile, was bubbling with enthusiasm and admiration for the production. He talked of "miracles on a shoestring budget" and congratulated the Arts Council for "subsidising so manic a creature", albeit modestly.

Such enthusiasm did not diminish. When I interviewed him some 20 years after the original Liverpool production, he was equally ebullient and declared in all seriousness that “Ken Campbell’s production of Illuminatus! made Wagner’s Ring seem like a frog’s arsehole”.

The Cottesloe Line Up: Paul McKay, Gabriel Connaughton, Wayne Bell, Bill Nighy, Thirzie Robinson, Janice Murray, Prunella Gee, Christopher Fairbank (courtesy of Chris Bernard)

The Cottesloe Line Up: Paul McKay, Gabriel Connaughton, Wayne Bell, Bill Nighy, Thirzie Robinson, Janice Murray, Prunella Gee, Christopher Fairbank (courtesy of Chris Bernard)

So profound was the impact of Illuminatus! that Peter Hall sent a team of very establishment theatrical persons to Liverpool to check it out. The production was snapped up to open the newly completed Cottesloe Theatre at the National. Thus underdog Campbell had forced his way into the conservative establishment without any compromise to his own principles.

The Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool flourished and became one of the most productive periods of Ken’s very productive theatrical lives. Some shorter productions, The End is Nigh, a post-apocalyptic romp, and Psychosis Unclassified, an adaptation of a Theodore Sturgeon short novel Some of Your Blood, were followed by another major blast, a 24-hour theatrical experience called The Warp.

On paper, this epic piece of theatre was written by Neil Oram and directed by Campbell, but in reality the process was much more collaborative than that and did lead to acrimonious disagreements between the two in later life.

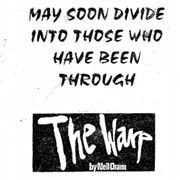

However, The Warp was a phenomenon. Michael Coveney made a radical statement that the company accepted as a manifesto: “The world will soon divide between those who have been through The Warp and those who have not”.

“Going through” The Warp was a good description, for the audiences were taken on a journey from a beatnik bohemia to the ecological communal living and free festival thinking of the post-hippie movements. It was 25 years of experience distilled into 24 hours of occurrence.

It was presented first at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, still under the banner of the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool. Later, it was revived for an Liverpool Everyman Theatre production when Campbell took over there as artistic director in 1980. There it played as a serial over 10 weeks.

This show is still fondly remembered in Liverpool and remains the World’s Longest Play, according to the Guinness Book of World Records – an accolade of which Ken was particularly proud.

Other Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool shows further explored the amazing and the epic legendary, including a staging of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy in which the audiences were put on a hover-diaphragm platform and moved around the theatre to sets placed on the outer perimeters, as well as a drastically-failed attempt to produce the same show in the 3,000-seater Rainbow Theatre.

There was a Science Fiction opera, devised from the H P Lovecraft novel The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, featuring the music of Camilla Saunders, actor Jonathan Hyde at his very best, and some of the best low-tech production values imaginable. Then there was a production of The Third Policeman, by Flann O’Brien, in which the problem of Irish accents, on behalf of the actors, was overcome by the use of distorted false teeth, hairy nostrils and spitting.

Campbell goes underwater at

Campbell goes underwater at

Liverpool UniversityFinally, there was a marvellous production of War with the Newts, based on the famous Karel Čapek novel, one of Ken’s favourites, where a huge water tank was placed on stage for the newts to inhabit and where actor-impersonators played well-known contemporary media and political figures.

This latter production proved to be a most forceful of establishment acceptance when harsh theatre critic Harold Hobson, long a detractor of Ken Campbell’s work, actually gave this an excellent review, describing with admiration the final scene, an enactment of Sir Robin Day and Malcolm Muggeridge sitting in a dingy, surrounded by endless desolation, contemplating the ruin all around them and debating it “endlessly, dispiritedly, aimlessly and uselessly”. That was a “Godot” moment indeed, and one that filled Ken with immense pride.

There was one other monumental event that the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool arranged as a swansong: The Great Underwater Concert. This remarkable happening took place in the University of Liverpool experimental pool, the Deep Pool, which was normally used for underwater diving research and other experiments in marine and aquatic exploration.

The audience Lighting equipment was installed on a rig, microphones and underwater sound equipment set up. There was a buzz of excitement. Actors, musicians from Liverpool band The Lawnmower and poets were on the poolside, the audience was in the water with snorkels and aqualungs.

The audience Lighting equipment was installed on a rig, microphones and underwater sound equipment set up. There was a buzz of excitement. Actors, musicians from Liverpool band The Lawnmower and poets were on the poolside, the audience was in the water with snorkels and aqualungs.

Tables and chairs were fixed to the base of the pool, people sitting on them, breathing through aqualungs, passing them round like joints, and having a party. The music, the poetry and other sounds, whale and dolphin singing, was played into the water through special sub-aqua speakers and acoustic pipes designed for communicating with marine mammals.

Writer and poet Heathcote Williams wrote a special epic ode to Leviathan, which would later become the best-selling book Whale Nation, and this was recited from the poolside with music by Camilla Saunders and Lol Coxhill. When actor Neil Cunningham performed the poem on the bank of the pool, anyone above water would hear it normally, whereas those underwater would hear it in a completely different way, almost as if the sound were entering the body through the skin.

As Ken said: 'The notion was that we would bathe in music. The thing being that sound travels three and a half times as fast in water, than it does in the air, unbelievably. Sounds like it should be the other way round. It goes faster underwater. And the thing is, you can hear sounds underwater, but you don’t hear them with your ears, they go straight into your body.'

This was a sublime finale to the visionary antics that were the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool, bathing in the Pool of Life that Jung had dreamed about, that Peter O’Halligan had interpreted and Ken Campbell had brought into reality. It had been a great decade or so of magnificent theatre and those who experienced will never forget, whilst those who missed it can only listen to the tales.