The revered wizard of odd brings talk of tricksters, witches and cosmic thinkers to Liverpool Confidential ahead of his city appearance

A CORNER of the Dingle becomes the centre of the groovy multiverse this weekend when a "gathering of the tribes" descends on the Florence Institute.

Yes, it's April 1, and it would be foolhardy not to celebrate the moment with legendary DJ Greg Wilson and a ship load of people here for his Super Weird Happening.

Top of the bill is revered writer Alan Moore – creator of Watchmen, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and the “genetic mythology” of recent novel Jerusalem.

You can get the full lowdown, as revealed by Liverpool Confidential, here. But meantime, Northampton's greatest export is going to rock you with his magic list of mystics and magicians.

1: Alexander of Abonoteichus (c. 105-c. 170): The Puppet Master

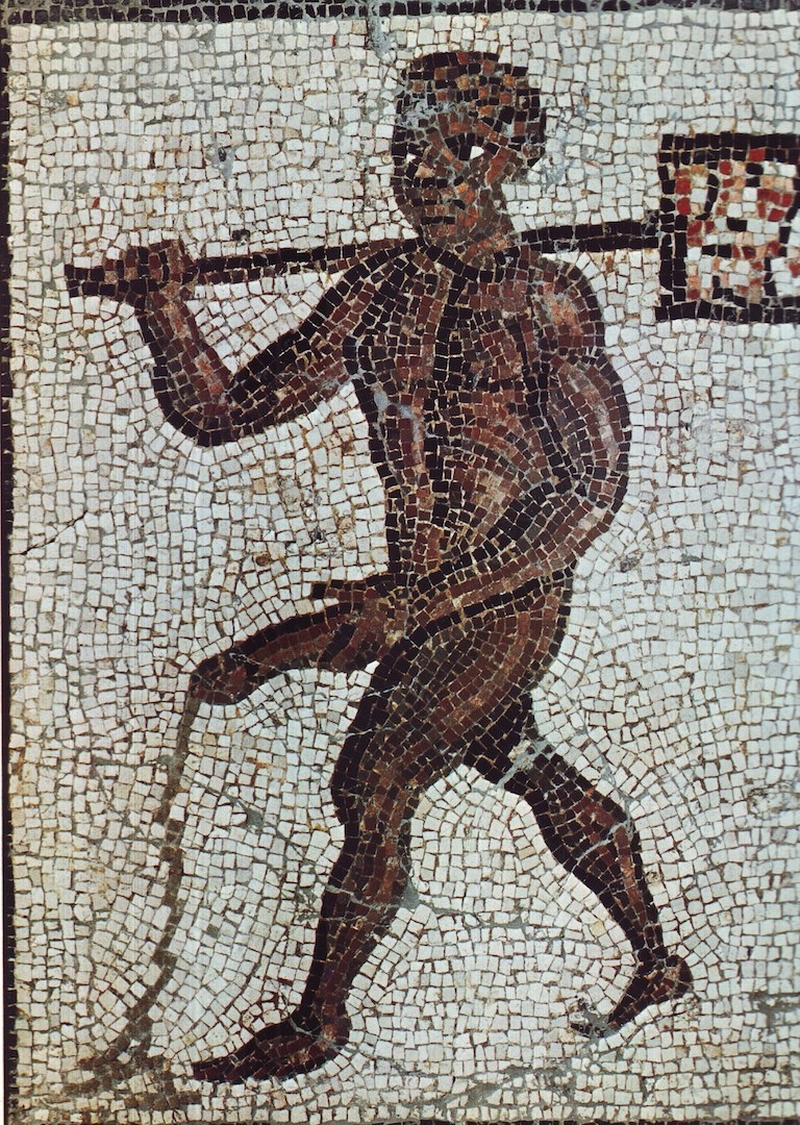

This first-century Black Sea Gnostic is mostly known from the vituperative account of his rival sophist (a kind of stand-up philosopher), Lucian of Samosata, who depicted Alexander as a former rent-boy turned dodgy remedy salesman, alleged paedophile and occult conman with his obviously fake, talking snake-god, Glycon.

A less biased reading by modern historians, however, allows us to assert that, whatever else he was, Alexander was definitely a Pythagorean and equipped with the latest Pythagorean ideas including the concept of “statue animation”.

This basically involved meditating strenuously upon a statue or image of a god until it was felt that the conceptual essence of the deity was somehow implanted within the icon, allowing a direct communion between the god and its worshipper.

By employing new techniques of stagecraft and ventriloquism in his creation of Glycon, Alexander was able to up the game with a kind of sophisticated, hi def theology where the image would also be moving and able to answer back. He established his three-day “Mysteries of Glycon and Selene”, a mystical and theatrical event that sounds like the precursor to a modern music festival.

Glycon’s cult lasted for 150 years after the death of its founder before being obliterated, like all the other Gnostic faiths, by the rise of Christianity.

Alexander is the first magician whose existence we can actually prove and the creator of the last classical god, practising a very sophisticated and illuminating form of magic on the very brink of the Dark Ages. Surely this shifty snake-handler is deserving of a reappraisal?

2: Dr. John Dee (1527-1609): The first 007

This Elizabethan magus is, for my money, the most creative and influential practitioner of magic who has ever existed. A brilliant 16th century mathematician and astronomer/astrologer, adviser to Queen Elizabeth I, Dee (literally) wrote the book on navigation that helped to establish Britain’s famous sea power; coined the phrase “British Empire” and suggested its implementation, to Elizabeth, in the colonising of America.

- He provided the basis for most modern Western thought with simply the books that remained in his Mortlake library once the mob were done with it;

- Was the inspiration for Ben Jonson’s Alchemist, Marlowe’s Faust and Shakespeare’s Prospero;

- Served as a secret agent in Francis Walsingham’s prototypical British Intelligence under the code name/number 007;

- Greatly improved the design of Manchester while losing most of his family to the plague;

- Spent most of his later life in communication with entities that he diplomatically referred to as “angels”, and who had revealed the complex structure of their universe and their “Enochian” language to Dee and his sometime partner, Edward Kelly through the agency of a crystal ball or scrying mirror.

John Dee pretty much built the modern world that we exist in, and his Enochian magical system at least appears to work if approached according to his instructions. They don’t make magicians like that any more.

3: William Blake (1757-1827): The Cosmic Creator

Blake summed up the artistic, anarchic soul of magic with his statement, “I must create my own system or be enslaved by another man’s”, and he certainly lived by that difficult dictum.

Though knowledgeable about subjects such as kabbalah or the transcendent teachings of Immanuel Swedenborg, Blake created his own intricate cosmology and expressed it through his visionary art and writings.

And though his gaze saw eternity in a grain of sand and raised an ethereal, fourfold, eternal city over the reeking slums of 18th century London, he was fiercely grounded in material and political reality. Politically a radical, he’d waved his red cap exultantly while watching Newgate prison burn and suffered sedition trials for repelling an attack by a drunken British soldier. He saw celestial or demonic visions on the stairs of his Lambeth home, sat naked with his wife Catherine in its garden, and was a friend of Tom Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin.

He could not tolerate cruelty, to people or animals, and if you read his poem London it could have been written last week. He left a glorious body of work that allows us spiritually anaesthetised moderns to catch a glimpse of the archetypal world that he inhabited.

As an artist, as a mystic and as a human being, it is very, very difficult to improve on William Blake.

4: Aleister Crowley (1875-1947). The wickedest pantomime villain

To be honest, if there was any way of avoiding Aleister Crowley in this roughly chronological list – say, in favour of at least one female magician like Dion Fortune or Rosaleen Norton – then I would have gladly taken it, given both the enormous attention that Crowley has received already and the fact that much of this is from sensitively reared thrill-seekers who are attracted to Crowley’s reputation as the world’s wickedest pantomime character.

But there isn’t really a way that Crowley can be ignored. His practical experience of magic is obviously vast, and his explanation of it is usually as accessible and as lucid as anyone could conceivably manage.

Although it follows on from the work of Éliphas Levi and the magicians of the Golden Dawn, Crowley’s greatest accomplishment is his beautiful and elegant synthesis of a wealth of pre-existing magic systems and magical ideas into one coherent philosophy and methodology.

Some of his books – Magick in Theory and Practice, Liber 777, The Book of Thoth, The Vision and the Voice – are essential for an understanding of the magic landscape, and the Thoth tarot deck he created with Lady Frieda Harris is, to my mind, still unsurpassed.

Too bad he had to discourage all of the proper scrutiny his important work deserves with his publicity-stunt Satanic posturing, but it’s undeniable that he provides magic with lot of its entertainment value, for better or worse.

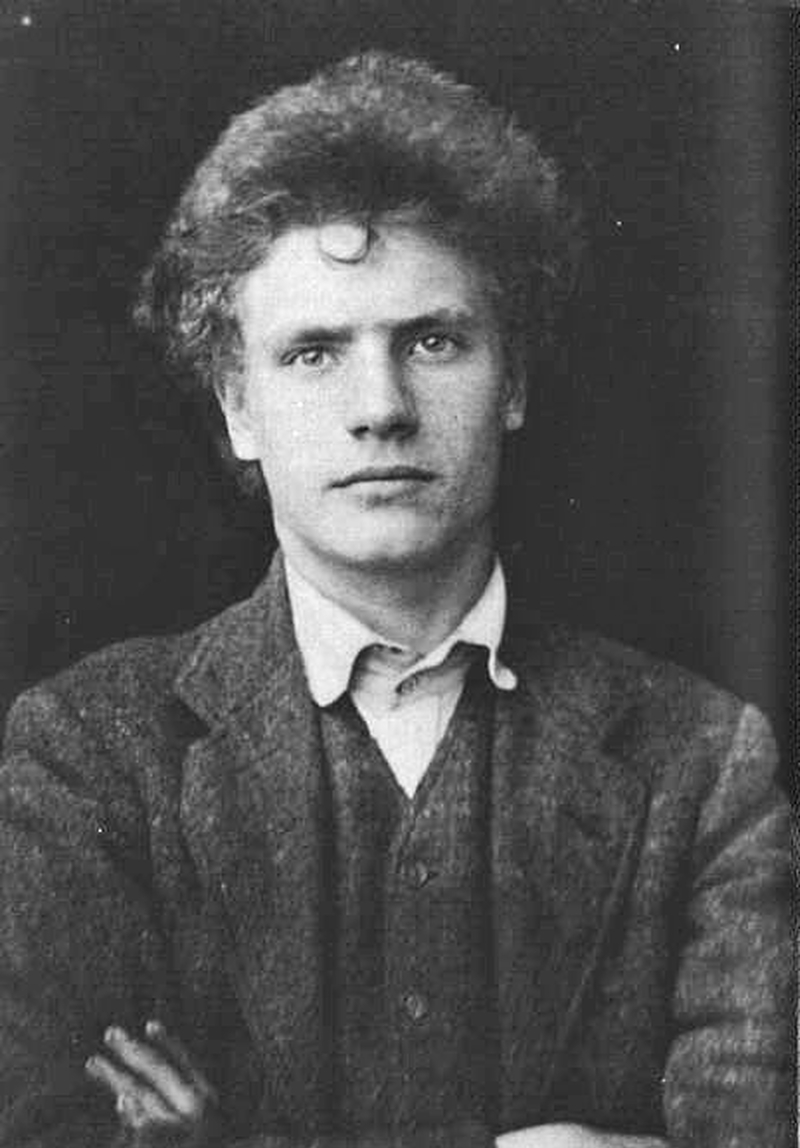

5: Austin Osman Spare (1886-1956): Magic with the common touch

The only authentic successor to William Blake, Austin Spare was an artistic prodigy who was hung in the Royal Academy from the age of 16 and, during his student days, was a teenage crush of the future Mrs. Pankhurst.

Turning his back upon his middle-class upbringing and the west end gallery lifestyle that could have been his, he went to live in south London amongst his preferred company of prostitutes, criminals, working people and a lot of adopted stray cats, working on his art, his writings and his uniquely personal self-created brand of magic.

The stories about Spare as an immensely powerful Brixton diabolist, while colourful and exciting, are nowhere near as convincing as the extraordinary power of his art, its grotesque and melting vistas giving the impression of landscapes and entities actually perceived and experienced. Spare’s earthy populism – he chose to exhibit only in pub back rooms and, when he died, left everything (which wasn’t a lot) to the RSPCA – is perfectly balanced by his ethereal mysticism.

He knew and possibly shagged Aleister Crowley, but regarded Crowley as “an Italian ponce out of work” and utterly rejected Crowley’s lore-bound and formal magical system.

Spare was approached sometime in the 1930s by Adolf Hitler with a request that he paint the occult-obsessed fuehrer’s portrait, which he declined, replying “if you, sir, are the superman, then I am proud to remain an ape.”

When Spare and his Brixton studio were later bombed during the Blitz, Spare suffered some kind of stroke and was left paralysed down his right side, including his drawing hand, but, being Spare, he simply taught himself to draw with his left hand and then, when his right side subsequently recovered, could draw with both hands at once. A working man’s magus, Austin Osman Spare is in my opinion the most important English magician of the 19th and early 20th century, Crowley included.

A savage, south London saint.