“CONFUSED?” My heart sank.

“Confused” was code for what coppers called “crazy and a pain in the arse.”

I picked up my baton and looked back the smart, detached house behind the lady I was talking to.

“Is she violent?”

“Oh no, she is 70,” the lady replied, twisting a tea towel.

I frowned. All “70” meant was I wasn’t allowed to hit her back.

I heard a car drifting into the kerb behind me and I turned, one hand on still on the baton, the other lifting the peak of my cap a little.

It was Colin. He nodded to me as he switched off his engine. I frowned and then turned to look back at the house.

“Tell me why you called?”

“She was standing in the road, confused.”

“She’s not the only one.”

“She said she was lost.”

“And she lives here?” a picture was forming that was not yet an assumption. “What’s her name?”

“I don’t know.”

“You her neighbour?”

“Yes.”

“Have you only just moved in?” I looked at her.

“Five years ago,” the neighbour looked away.

I nodded. Modern neighbours. I couldn’t judge, I was one of them. Colin joined us, half a pace behind me; I was there first so I was the lead.

“I’m going to knock on the door, could you stick around so she can see a friendly face?”

The neighbour nodded. I knocked. We waited. I knocked again. We waited again. I looked at Colin. We waited.

I sighed, and then knocked once more as he went around the back of the house. I took a step back and then opened the letterbox, waiting a moment before I put my eyes near the opening, just in case anyone inside had anything sharp.

She was in the hallway, wearing a long coat that should have stayed in the cupboard for another three months, and carrying a handbag that was big enough to hide the Queen Mother in.

“Hello?” I said. She smiled.

“Could you open the door please?” She smiled.

“It’s the police; I was hoping to talk to you?” She smiled.

I closed the letterbox and turned to the neighbour. “Do any neighbours have spare keys?”

“I don’t know.”

I wasn’t surprised. The tea-towel twisted, this time in embarrassment.

I turned back to try again at the letterbox, but the door opening beat me to it.

I looked up. Colin looked down.

“Back window,” he said, as ever a man of few words.

I followed him into the hallway. The old lady smiled at me, like it was perfectly normal to have a policeman climb in through a kitchen window and open the door for his less agile colleague.

“Hello,” I said.

“Have you brought my dinner?” she replied.

“No, have you not had your dinner?”

“I don’t think so.”

I nodded, listening to Colin as he made his way around the ground floor of the spick and span house.

“Do you live alone?”

“I live with my husband.”

Colin was passing behind her when she said this. Our eyes met, we both sniffed the air for sign of a dead man.

“Where is he?”

She frowned, I frowned, Colin frowned, and then looked up the staircase to his left.

“He has gone out.”

Colin and I stopped frowning and Colin started to climb the stairs.

“Where has he gone?”

“I don’t know.”

“Does he have a phone?”

“Yes.”

I brightened, then faded as she pointed to the landline telephone that sat like a plastic toadstool on a table by the door.

“That’s it.”

Colin appeared at the top of the stairs and shrugged.

Nobody, and, more importantly, no bodies upstairs.

I pointed towards the living room.

“Shall we sit down?”

She nodded and slowly led the way into the living room like she’d never been there before. She sat, handbag balanced on her knees, a curious uncertainty in her face, a whisper of doubt, like someone unsure of something trivial.

I heard a kettle being filled somewhere not far away.

The neighbour hovered by the threshold, half in half out with lingering glances to the still open front door.

“What is your name love?” I said it quietly, with a smile. Even though we weren’t supposed to say “love,” there were times when “madam” didn’t seem right.

She smiled back, she looked younger. She told me her name and then looked back at the window, suddenly old again.

“When did your husband go the shops?”

“He’s gone the shops.”

“I know love, when did he go?”

She put a shiny pink knuckle to her lips.

“I don’t know,” she said almost to herself, with a sudden brimful of eyes.

I sat down next to her, all body-armor and clatters of plastic and metal. I put my cap on the floor like a dog bowl, and she looked down into it and then up at me.

“Shoey?” she said, reading my nickname out of the inside.

“Yeah,” I smiled because she looked so young again, her eyes like a child’s.

“Do you have children?” the eyes danced, and I could see the watery window reflected in them.

“No I don’t.”

“I’ve a daughter lives in London, she is a doctor.”

“Wow, you must be very proud.”

“I am,” the smile again.

Colin put some sugary tea down and she gave him that smile as well. Colin didn’t smile much as a rule, but he did for her. She broke the rules.

I looked at the neighbour.

“Have you seen the husband?”

“Today?” the neighbour replied, maintaining her winning streak of being totally useless to me.

“Ever?” I replied flatly.

“His car was there this morning.”

I perked up.

“What kind of car is it?”

“A little yellow one.”

Great, I was looking for Noddy.

Colin appeared in the doorway, I hadn’t noticed him leave the room, he was good at that sort of thing. He was holding one of those little phone books we all used to have. The kind of phone book that was full of doodles and numbers, and swirls of ink and scratches that came from almost dead pens that were struggling to start.

I looked at our old lady. “What is your daughter’s name?”

She told me. Colin flicked pages, nodded, and then disappeared. Two coppers working without words.

I heard long distance dialing on an old rotary phone and waited.

And waited. And waited. And waited.

Then the phone was put down. Nobody home.

“Do you know where she works?”

“Who?”

“Your daughter?”

“She’s a doctor.”

“Do you know where?”

“What?”

“Your…” I faded away and adjusted my body armour. “Drink some tea.” I said and she saw the cup waiting.

She leaned forward as I looked at Colin, back in the doorway, back turning pages in the old phone book.

“Shoey?” she said.

“Yes?”

“Is that your name?”

“Yes,” softly again.

“Do you have children?”

“No.”

“My daughter’s a doctor.”

I looked at the neighbour.

“You can go, thank you for your help.”

She nodded, twisted the tea towel and then left. At least now she knew her neighbour’s name.

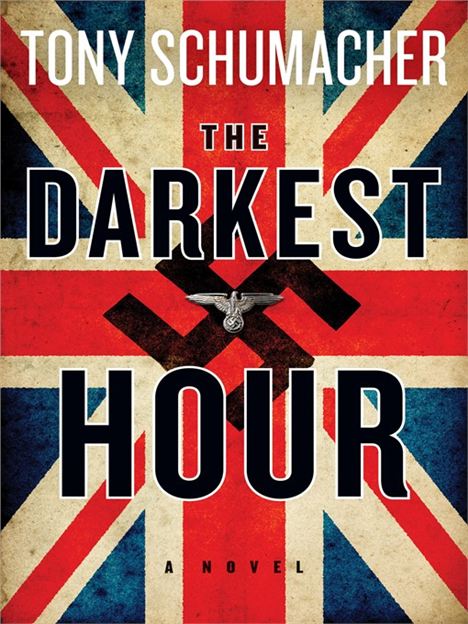

Tony Schumacher's debut novel, The Darkest Hour, is a thriller set in German-occupied post-war London.

It is published by Harper Collins, £7.99 and is out now.

It is safe to say that he's not driving a taxi any more.

Follow him on twitter @tonyshoey