YVES Klein was a visionary showman with an expansive approach that led him to erase the boundaries between life and art, anticipating later movements such as pop, performance and installation.

His work leads three new exhibitions, on the top gallery of Tate Liverpool.

As well as Klein's Theatre of the Void, we have the first UK retrospective of Polish artist Edward Krasinski, Director of Spectacle, and Cécile B. Evans' new multi-dimensional installation, Sprung a Leak, featuring two humanoid robots and a robot dog.

Each portrays a pivotal phase in European art: from post-war flux to post-millennial technological advance.

On one hand, Klein focuses primarily on the use of pure colour to challenge any preconceptions of either subject matter or context in what can be best described as “immaterial sensibility”.

Klein: Leap into the Void, 1960

Klein: Leap into the Void, 1960On the other hand, Krasiński explores the realms of minimalist sculpture and artefact through an intense devotion to mathematical convolutions of line, shape and occasional colour. Underpinning this is a desire to strip-down their inherent basic elements to create abstract configurations.

Finally, Evans Sprung a Leak explores the complex relationship between humans and machines using state-of-the-art technologies to i'nvestigate how they respond to each other’s sense of identity and co-existence.

In terms of Klein’s work, having experimented with various pigments and applications with sponges and rollers, he created a synthetic deep ultramarine blue, subsequently inventing it as IKB [International Klein Blue] having been influenced by seeing Giotto’s frescoes at Assisi.

These monochrome canvases became his signature theme throughout Klein’s career, imbuing a sense of meditative contemplation which underlined a respect for East Asian enlightenment. Indeed, he became proficient at judo as well as practising katas which involved the synthesis of the human frame in both a pictorial and spiritual space.

Over time, these elements coalesced and, in 1960, he created a piece of performance art in which a number of naked female models daubed themselves with IKB and made prints both against a wall as well as being dragged across the floor whilst a music quartet played in the background. Shock value? Of course, and deliberately so. Klein obviously thought it would result in his elevation as the artistic Pimpernel of the emerging French nouveaux réalisme movement of the 1960s together with Pierre Restany, though it all seems quite tame by comparison now.

The resultant prints include one with a lipstick kiss and, I suspect, Adrian Henri would have loved every minute of it. That said, they’re reminiscent of the kind of images which resulted from sitting in various positions on a photocopier. Apparently.

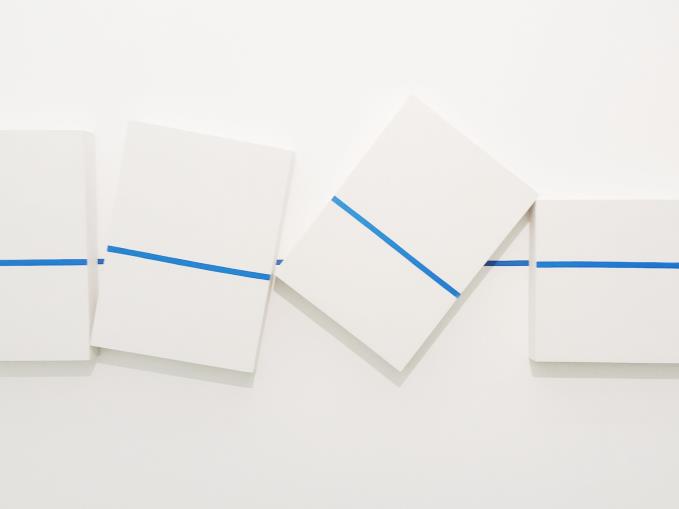

Next, given the degree of simulated simplicity of Krasiński’s uber-minimalist sculptures, you only have to scratch the surface to reveal his playful, even humorous, nature. By example, marking the whole of the interior gallery space with blue scotch tape sticking it at the height of 130cm. This became his individual hallmark as he later explained “A line is a coincidence but I expected that”.

Krasiński: Interventions, 1980

Krasiński: Interventions, 1980That said, credit must be given for the curatorial team who put all together since it was spot-on, particularly the hall of hanging mirrors which beckoned the viewer in to a bewildering multi-dimensional environment. The various Interventions and Compositions were intriguingly juxtaposed with their own shadows for additional perspectives with sparing use of colour.

Similar trends were taking in the Italian Arts Povera movement of the time – a good example can be found in work of Marisa Merz in the Constellations collection at the Tate. In the context of the time, you get the sense that Krasiński was using his individual avant-garde approach to counteract the prevailing art-of-the-state ideology imbued within the walls of Warsaw’s Palace of Culture and Science. Not an easy task but he managed to achieve it with a wry smile as he blurred the taken-for-granted distinctions between art and everyday life.

Finally, by way of contrast, a glimpse at the various installations by Evans’ on the ground floor. It’s very much an interactive experience with pirouetting humanoid robots, a succession of LCD flat-screen pole dancers and NASA Challenger piggy-backs and a cubic water feature all contained within a stark-white gallery.

Sprung a Leak

Sprung a LeakBetween the three, there’s a deliberate attempt to downplay the role of the artist altogether in order for the works to somehow “speak for themselves”. However, Klein tends towards creating a more ego-driven context as evident in his filming of his events, namely the Anthropmetrical phase of the Blue Period and successive Fire pictures.

Krasiński is, by contrast, more subtle in both initial inspiration and execution. To be frank, his abstractions tend to bring you in for closer inspection rather than simply staring at identical panels of deep IKB.

Evans simply does away with the very act of the artistic endeavour by incorporating binary code instructions to instruct his robots to graze around the room, making occasional announcements to bewildered on-lookers. It’s another aspect of spectacle, albeit in polished white plastic and huge LCD screens, but ultimately sterile.

*Yves Klein/Edward Krasiński/Cécile B. Evans, Tate Liverpool, Albert Dock, until March 5, 2017