ABOVE any other metropolitan city in the UK, Liverpool is recognised for its special relationship with the Irish. It must be something to do with being on the outermost fringes of the continent and you could, also, throw in the shared experiences of a Celtic heritage, the sea-faring, the adversities of casual labour and propensity to dream of better days.

So, to coincide with the forthcoming annual Irish Festival, the Liverpool Playhouse has teamed up with the Bristol Old Vic to produce one of the classics of contemporary Irish drama.

Most of us have some understanding of the context of the Irish "Troubles" which, in itself, is an understated metaphor for decades of deep internecine rivalries suffused with religious bigotry, the struggle for self-determination and divided loyalties across the divide. It wasn't too long ago that the problems seemed insurmountable as yet more innocent people lost their lives to justify a never-ending cycle of violence.

Louis Dempsey, Des Mcaleer and Aoife Mcmahon. Pix by Stephen Vaughan

Louis Dempsey, Des Mcaleer and Aoife Mcmahon. Pix by Stephen Vaughan

This is the world in which Sean O'Casey knew of as home turf. Life was incessantly bleak, people went hungry, men drank to oblivion and women had more children than they could cope with. The communities of the slums were born into, lived and died in a wretched state of "chassis".

The Civil War drama focuses on the shenanigans of the Boyle family being steered towards the rocks by their own “Captain Jack" (Des McAleer) with his stooge/drinking partner “darlin” Joxer Daly (Louis Dempsey). All this is much to the exasperation of long-suffering wife Juno (Niahm Cusack) who has to keep everything together, including a wayward daughter Mary (Maureen O’Connell) and a debilitated son Johnny (Donal Gallery) following a failed ambush as a volunteer.

Salvation seems to arrive with the unexpected prospect of a legacy left by a distant cousin and delivered by an effete English Wooster-type, Charles Bentham (Robin Morrissey). This sparks off a spending spree on the never-never, with a house party to match it, including neighbour Maisie Madigan (Aoife McMahon) to spice things up a bit. As Yeats put it rather well, things began to fall apart when the centre could not hold. In this case, the consequences of a poorly-written will which gives carte-blanche to every first and second cousin in the 32 counties to lay claim to the inheritance.

Eventually, Bentham can’t be traced to sort it out as he’s scarpered back to England, leaving Mary pregnant. When the debts start to roll in, the new furniture has to go back, even Maisie resorts to claiming the new gramophone player to pawn. One by one, each of the magnificent tail feathers of the Paycock are cruelly yanked out as his world begins to implode. Their collective dreams were never to see the light of day, no matter how many stars looked down in their favour.

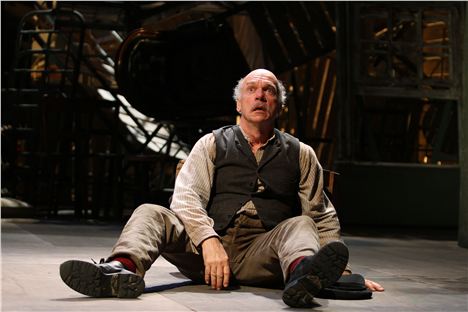

The finale sees Captain Jack and Joxer in a state of drunken stupor, the dawning realisation that his world has come to a crashing conclusion. The final line sums it all up… "Th' whole worl's in a terrible state o' chassis".

O’Casey said himself later in life, “the tenements were full of hardship and hope, with plenty of laughter and drinking. But, beneath these were much sorrow, darkness and death”.

This production goes some way to reveal the spectrum of that, particularly when all hope seems lost as Juno implores for divine intervention to come to her aid. One of the most powerful moments arises when she cries out in agony after Johnny has been executed for treason by his erstwhile Republican Army compatriots…”Blessed Virgin, where were you when me darlin’ son was riddled with bullets? Sacred Heart o’ Jesus, take away our hearts o’ stone, and give us hearts o’ flesh!”

So, much credit for this joint collaboration and for Gemma Bodinetz’s commanding direction. Credit, also, the staging and set designers who came up with an ingenious barricade of assembled chattels and bric-a-brac which Albert Steptoe himself would have been proud.

All in all, the ensemble gives polished performances in a play that condenses many themes of its day. The passage of time has diluted its original shock value (it was first staged at the Abbey in Dublin in 1924), and you could argue that O’Casey fitted too much in for dramatic effect. But, without doubt, this play reflects a good deal of the lived experiences of the tenements’ own troubles of the day. Worth a trip.