THE value of art as a political dynamic is well-established. Ruling classes since the Renaissance favoured the works of the Great Masters to instil elite establishment values, often linking material wealth and privilege with heavy religious and imperialistic overtones.

These can be found in many municipal galleries around the country – the large canvases within ornate frames, the country houses, the idyllic rural scenes, the glories of conquest. Yet, you may ask, was life really like that for the rest of society?

The artistic means of production in the 21st century, whether it be photography, printing,

digital or any other media has seen a seismic democratic shift away from the elite

Alternatives certainly did exist and would make eventually make their mark to prove that the peasants, then the working-classes, could celebrate their own culture and identity across the increasingly fractured social structures emerging from the Industrial Revolution.

In order to assess this, Tate Liverpool has provided a opportunity to discover how, what and why this all happened.

Atelier Populaire 1968Not only that, it’s on a grand scale covering nearly every inch of the 4th floor – everything from trade-union banners AND hand-printed agitprop posters from Paris in 1968, samizdat Situationalist leaflets, the images and reports from Mass Observation and much more. Liverpool hasn’t seen anything like this since the opening of the People’s Republic gallery at the Museum of Liverpool.

Atelier Populaire 1968Not only that, it’s on a grand scale covering nearly every inch of the 4th floor – everything from trade-union banners AND hand-printed agitprop posters from Paris in 1968, samizdat Situationalist leaflets, the images and reports from Mass Observation and much more. Liverpool hasn’t seen anything like this since the opening of the People’s Republic gallery at the Museum of Liverpool.

Given the range of themes involved, some issues need to be addressed. Art as Propaganda is probably the most obvious. These range from early Bolshevik posters of Lenin, Molotov and the other Russian Revolutionaries, some with intriguing Arabic script, to recent Chinese prints depicting “The Production Brigades Reading Room” (main image, top). Well-scrubbed happy workers all.

Compare these to the camaraderie of labour activism through the lens of British Victorian trade-unionism and we arrive at a more down-to-earth Walter Crane and William Morris. These two embody a utilitarian socialism which promoted artisanship, influenced by the craft movement, rather than collective struggle against the bosses.

Crane’s Utopian view extols the solidarity of [worldwide] labour. Interesting to see an original Kelmscott Press “News from Nowhere” from Morris, as well as some textile design prints and hand-printed wallpaper.

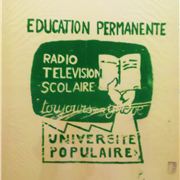

At the other extreme: “sous les pavés la plage” and the symbols of the student/intelligentsia/trade-union General Strike of revolutionary Paris in May 1968. These really capture the mood of the time through hastily-silkscreened satirical posters by Atelier Populaire attacking the Establishment, de Gaulle in particular. This was class-warfare writ large and they certainly had a revolutionary impetus at the time.

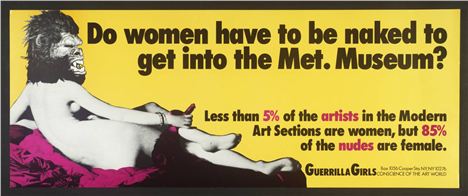

A more recent phenomenon was the emergence in 1985 of the Guerrilla Girls whose by-line was “conscience of the art world”. Post-feminist, yes, but still using street-media to attack the male-dominated art establishment in the US. The same could, also, be said of the Hackney Flashers [a women’s collective] who sought to expose the inequalities of domestic drudgery, low-paid work and lack of opportunity.

Then we come to the downright anarchic through various offshoots of the Situationalist International in the form of the Guy Debord, King Mob and Black Mask. Their output ranges from a homage to the Luddite Rebellion to the taking over of a West End Christmas Grotto and giving out all the presents to the kids for free. Likewise, Meireles preferred a more anti-capitalist approach. In this case, he put political slogans onto Coca-Cola bottles and returned them to the supermarket.

The work of Mass Observation isn’t so much left-wing socialist as popular-culturalist.

Insertions Into Ideological

Insertions Into Ideological

Circuits - Cildo Meireles 1970Initially, Madge and Jennings were keen to develop social anthropology with an emphasis on documentary records to reveal the often unseen lives of the working-classes in Britain. This was the catalyst for both Grierson’s G.P.O Film Unit but, also, the keeping of diaries by ordinary people. Humphrey Spender was invited to become the photographer/agent-in-the-field and this collection is a rare opportunity to see at first-hand how people and their communities dealt with the daily grind of everyday life.

There are a couple of quite unusual additions which, although avant-garde, seem out-of-place. These include a kinetic installation, a golden cloth where you can stitch your own personal work, a piece called Retrograde [which serves to underpin collectivist credentials] and a variety of modernist sculptural pieces by Hendricks.

There’s even a drop-in “Office of Useful Art” at the heart of the exhibition which they describe as “promoting the idea of art as a process – a part of everyday civic life rather than simply a rarefied spectator experience”.

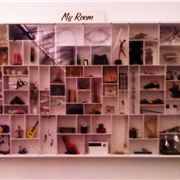

Now that’s original and if it works as they hope, then there could be an important legacy factor. At the very least, it goes some way to transform the visitor experience into something more potentially creative and participatory. To show how this could happen, there’s a collaborative piece [My Room] produced by the locally-based Black-E project which confirms the fact that art can, indeed, be a positive exercise.

![News From Nowhere [Kelmscott] 1893 News From Nowhere [Kelmscott] 1893](https://assets.confidentials.com/uploads/imported/i/MQB/6Q23_K.jpg) News From Nowhere [Kelmscott] 1893

News From Nowhere [Kelmscott] 1893

Overall, given Liverpool’s own history of union militancy and intermittent civil unrest, it seems fitting that Tate Liverpool should choose to explore the creative dynamics within movements which reflect left-leaning core values - although it will cost you £8 to get in.

The works on display illustrate the wide number of personal and communal interpretations of this, yet it’s perhaps ironic that they’re being shown in a converted dock warehouse and funded through the philanthropic generosity of one of the Victorian grandees wealthiest families.

My Room - Black-E ProjectThat said, Art Turning Left asks more serious questions about the current state of the art market, individual/collective creative effort and the importance of the political context[s] which influence struggle and resistance to help deliver change.

My Room - Black-E ProjectThat said, Art Turning Left asks more serious questions about the current state of the art market, individual/collective creative effort and the importance of the political context[s] which influence struggle and resistance to help deliver change.

One thing is certain, the artistic means of production in the 21st century, whether it be photography, printing, digital or any other media has seen a seismic democratic shift away from the elite. It may not be entirely Utopian, but it’s unquestionably egalitarian.

Indeed, we are all capable of creative expression now so, if you think that the system is unfair and life needs to change for the better, then this exhibition basically says "No more excuses…just get out there and do something about it”.

*Art Turning Left, Tate Liverpool, Albert Dock, L3, until February 2, 2014. Adult £8.80 (£8 without donation). Concession £6.60 (£6 without donation).