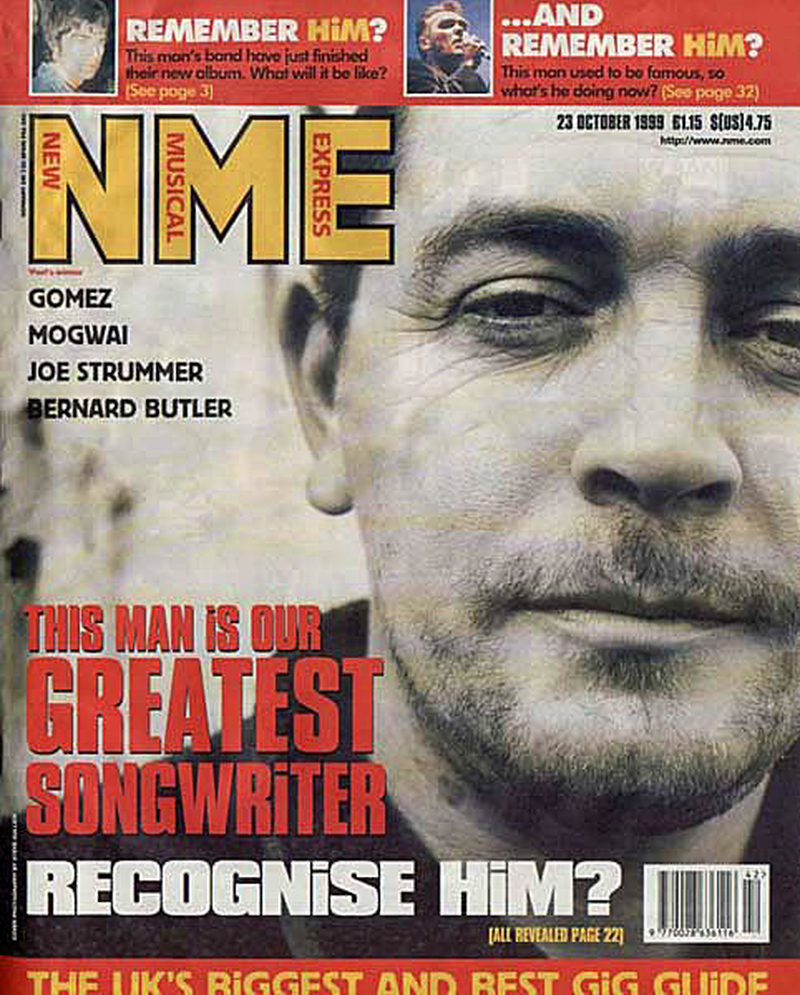

On the eve of the release of his first album in a decade, the man once dubbed 'our greatest living songwriter' talks love, loss and redemption. By Gerry Corner

AFTER his tragicomic tumble, worse for wear, from the stage of a dry bar, it looked like a long way back for Michael Head.

The man they variously call poet, dreamer, nearly man, our greatest living songwriter, Head had already accumulated his share of complications, even by pop star standards.

Now another attempt to invigorate the career of the man behind cult Liverpool bands The Pale Fountains and Shack, via a gig at recovery social enterprise The Brink, had fallen rather too literally flat on its face.

Fast forward five years… Sunday, June 19, 2016.

The cave-like surroundings of Liverpool’s Zanzibar Club. Rammed, sweaty, it would be claustrophobic if anybody cared. They don’t, because Head is tearing the house down.

Gone the glazed expression, nervous shuffle and anxious tics of previous performances. Tonight he is clear-eyed, smiling, in the zone. At a quiet moment, a member of the audience shouts out what they’re all thinking: “You’re on fire, Mick!”

That summer night at the Zanzibar, with his latest alliance, the Red Elastic Band, only those closest to Head knew for sure the secret of this metamorphosis, but for those standing out front, watching, the reason was clear.

It’s another 16 months down the line when I finally meet Head: lean, feeling strong, excited about the future. After 30 years adrift on a sea of drugs and alcohol, the boy from Kensington has come home.

I was like ‘no chance, I’m not going into Probe and buying fucking Sultans of Swing for you mate, they’re shit’. And he went ‘if you buy it for me you can have that guitar in the corner’

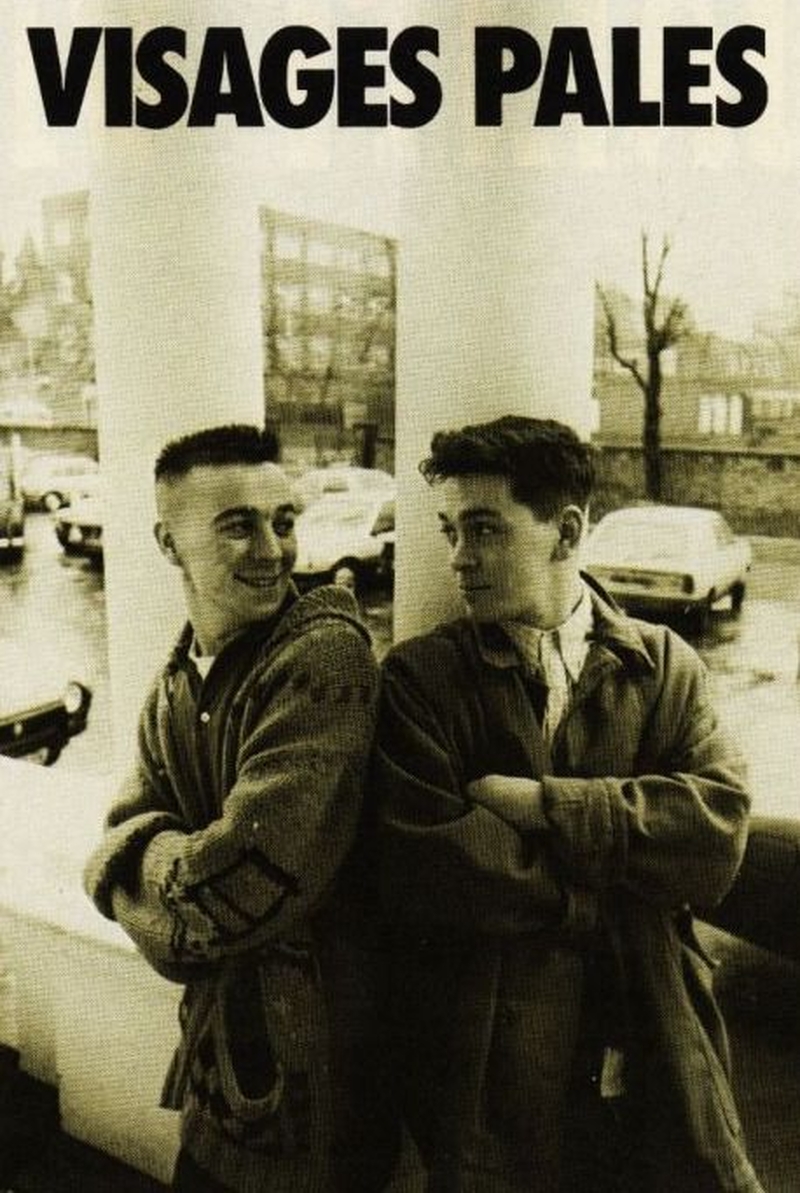

For those unfamiliar with the legend of songwriting genius Michael Head, it’s fair to say his life has not been entirely plain sailing. The Pale Fountains, his first band, signed to Virgin Records (almost 35 years ago to the day, as it happens) with a record-breaking advance, were set for stardom with their fusion of Arthur Lee and Latin rhythms, Burt Bacharach and Conan Doyle chic, bombed commercially in the UK, but won the hearts of France.

Head recalls: “With the Paleys, from day one, the French kind of took us on board because the English didn’t know what to do with us. So the French thought, well, we don’t get the English either.”

Shack, his second band, formed with brother John, harder edged, harder to define, drug-tinged “psychedelic folk”, made their much-acclaimed Waterpistol album in 1991 but didn’t manage to release it for another four years due to the recording studio housing the master tapes burning down and consequently going bust. By the time a stray tape was miraculously recovered from the glove compartment of a hire car, somewhere in New Mexico, and Waterpistol went on sale, via a German record label, it had missed the moment and joined Head’s growing list of “great forgotten albums”.

There’s more, much more actually: like backing his hero Lee, leader of influential LA rock band Love; the loss of Pale Fountains bassist and comrade in arms Chris “Biffa” McCaffrey to a brain tumour, major issues with drugs, major issues with drink and, along the way, somehow managing to compile the best least-known back catalogue in British popular music history.

Sometime next month he will mark two years off the bottle, a milestone he had truly believed was beyond him. Even the intervention of the law, in November 2015, failed to provide the necessary jolt. In the end it came down to a father’s love for his son.

Approaching his 57th year, there is now much to look forward to, most immediately a first studio album in over a decade, Adiós Señor Pussycat, with the Red Elastic Band, which is less a band, more a “fluid inclusive collective”, expanding and contracting according to the occasion.

Most of them get a look-in on the album, from some time members of Liverpool’s Sense of Sound Choir (Head’s sister Joanne included), to Nina (“we only know Nina as Nina”) on piano and Karina Townsend (wife of Pale Fountains trumpet player Andy Diagram) on hand saw (he’s on it too, along with Martin Smith, the REB’s more regular horn player these days).

Released this Friday, it has gathered a clutch of enthusiastic reviews already. A baker’s dozen exquisitely crafted “folk-pop” songs, all bar one written by Head between the late 1980s and the present day.

Liverpool photographer John Johnson’s album cover shows him wearing the smile of a man who has unburdened himself.

At the Florrie, the Dingle community centre he enthusiastically supports, Head is reeling off his to do list: a collection of short stories to be published by his Violette record label, another project with the Red Elastic Band, an album of piano pieces, a possible tour, a screenplay for which he has real hopes, and a trip round France in a Fiat Amigo (yet to be purchased) with “someone of the female species who I’ve got in mind”, which will end, all being well, with a gig in Paris.

The week before our first meeting I see Our Greatest Songwriter pushing his bike along Upper Parliament Street. Whether this new work, from a happily settled Michael Head, will finally bring the fame and fortune that have so determinedly avoided him, who can tell? But that really never was the priority.

Head says: “There’s no set agendas, no ulterior motives. We’ll do what needs to be done for the benefit of the album. We all need money obviously, it’s a necessity, but for me, personally, I’m a songwriter, I’m a storyteller at heart. I’ve been doing it since I was 17, and I want as many people to hear it for the songs as much as anything.”

That 17-year-old was a tea boy at Brian Green Business Machines in Liverpool when he unexpectedly acquired his first guitar. “I’d just left school. I think calculators were the new big thing. I was the peggy (‘peggin’ it everywhere’), the tea boy.”

The new recruit had noticed the boss had a guitar. “I’d pick it up and he’d come in so he’d obviously clocked me. And this day he goes ‘you’re into punk aren’t yer?’, and I said ‘well, bits of it’, and he goes, ‘in your lunch hour will go to that shop you go to,’ Probby, he called it, ‘and get me a punk record?’.

“And I said ‘no problem, what is it you want?’ and he goes, ‘er, Sultans of Swing by Dire Straits’ and I was like ‘no chance, I’m not going into Probe and buying fucking Sultans of Swing for you mate, they’re shit’. And he went ‘if you buy it for me you can have that guitar in the corner’. So I went to Bunny’s – miles away – and he said, ‘there you go’.

Now the young Mike Head had a guitar to play, he needed someone to play with: enter Biffa, aka Chris McCaffrey, a fellow resident of Kensington who would become his best friend, kindred spirit and fellow traveller with the Pale Fountains, their bond abruptly broken when, aged 28, Biffa was diagnosed with a terminal tumour on the brain.

“We were on different sides of Kenny but I used to notice Biffa because we had similar clothes. I’d played five-a-side against him, heard him play bass in the cellar of a pub called the Lord Seldon, but I’d never spoken to him.

“I had a copy of (Love’s album) Forever Changes and I thought he plays bass, I’m learning to play guitar, I’ll take a gamble here. I went over. His dad, Gordon, answered the door, and I said: ‘is your Biffa, errrrr…’, I didn’t know his first name, he said ‘do you mean Christopher?’ and I said yeah.

“I said ‘give him that, he might like it, and tell him to pass it back’. A few days later he passed it back and said, ‘I loved it’. I said, ‘come in’ and we had a cup of tea, said shall we form a band? and that was it.

“Biffa was like a brother. To tell the truth when brothers are 17, 18, they kind of drift apart, so it’s a different kind of brother. You’re at that age where you’re getting into adulthood and you’re inside each other’s pockets, you’re like a little unit.

“He was a beautiful man, beautiful lad. You know people say that thing, ‘he wouldn’t hurt a fly, he doesn’t have a bad bone in his body’ but you’re talking about the real deal there. So it was a big loss.”

Head was on the bill at the Liverpool International Music Festival in July, 2016, when talk of an album, which had begun a couple of years before, suddenly turned serious. In Sefton Park, he met up again with Steve Powell, producer of Head’s The Magical World of the Strands, paid for with French money, fuelled by heroin, co-starring brother John and widely considered his masterwork.

Powell’s son, Tom, the REB’s newly enrolled bassist, was on stage with Head at LIMF. Powell senior, there to lend fatherly support, liked what he heard and invited Head back into the studio.

Kismet, Head calls it. The Red Elastic Band’s regular drummer and bass player had both left at the same time so “meeting Tom and Phil (Murphy, another REB regular) who played bass and drums, at the time that I did, that was really kismetic, meant to be”.

“It was kismet meeting them and just a lot of things that happened within the album. Like on Picasso, Andy Diagram’s wife came in with a saw , she was picking him up to take him back to London. We said, get the saw out, she said ok, mic’d it up, and she does that eerie thing on the end of Picasso (the album’s haunting opening track) and it’s beautiful. Little things like that.”

Initially, Head had stalled over the album, unsure of himself. “I was thinking, nice idea, but it’s not really going to happen, because I don’t think I’m going to be able to cope in the studio without fucking up.

“I was still confident that my mindset about stopping (drinking) was intact, but I was having doubts about the world in general, things were starting to get to me, I couldn’t understand things.”

In the end, he says, the support of those around him pulled him through. “The lads in the band, they’re so chilled and turned on, and were there for me, from top to toe, emotionally.”

Booze had been “a massive crutch for me. I never thought I’d ever stop drinking.” He’d wanted to? “Oh god, yeah, wanted to for 10 years, I just thought, nah, that’s not going to happen.”

There is, he says, no going back: “There’s far, far too much to lose. Now I’ve actually got the opportunity to put my money where my mouth is.”

It does no harm that his new found partner is also teetotal. They met on a Virgin Intercity. “She was coming down to do PR for us. We fell in love on the train. By the time we got to Euston I’d sacked her and we were an item.”

She (in the course of three conversations, Head is careful not to refer to her by name) stopped drinking two months before his own life reached a turning point in the late autumn of 2015.

Here, for the first and only time, he is deliberately, understandably, vague on detail, but you’ll get the gist. “I suppose the end of it was getting arrested and having to leave the family home, knowing it was the right thing to do, taking myself out the equation.”

Alone in a bedsit on the other side of town, “I was obviously not in my comfort zone, where I’d been with my girlfriend for 25 years, and the lads (their two boys). I felt sorry for myself, carried on drinking with a demon vengeance.”

A couple of weeks later came what Head calls “the pivotal moment”. A telephone conversation that changed the course of his life. The call was from his estranged partner who was worried about Arlo, the eldest of their teenage boys.

“She said to me that Arlo, who’s on the autism spectrum, was getting picked on and he was crying. She told me Arlo had said to her that ‘it’s not worth it’ and that he’s got no friends and he’ll never have friends.

“I just slumped to my knees. I said to her, ‘I can fix that.’ And that was it. That was the day. I thought, yeah, I can fucking fix that.

“And I have to an extent, because when I said to him on Saturday what do you want to do, because he doesn’t ask for anything, you’ve got to draw it out of him like blood out of a stone, he doesn’t want the computer, so he goes, ‘where’s Ben Nevis?’, and I said it’s in Scotland, why? Because he’s fascinated by a lot of different things, and he said, ’I’d like to go there, check it out’. And I said 'well there’s Snowdonia, in Wales, and there’s Scafell Pike' and he said, ‘no, that’s the big one isn’t it?’ So I’m taking him there for his birthday.”

In some ways Adiós is just that, farewell to a former existence, the title borrowed from a Tom and Jerry cartoon and chosen, in part, for its “relevance to the whole moving on with my past”.

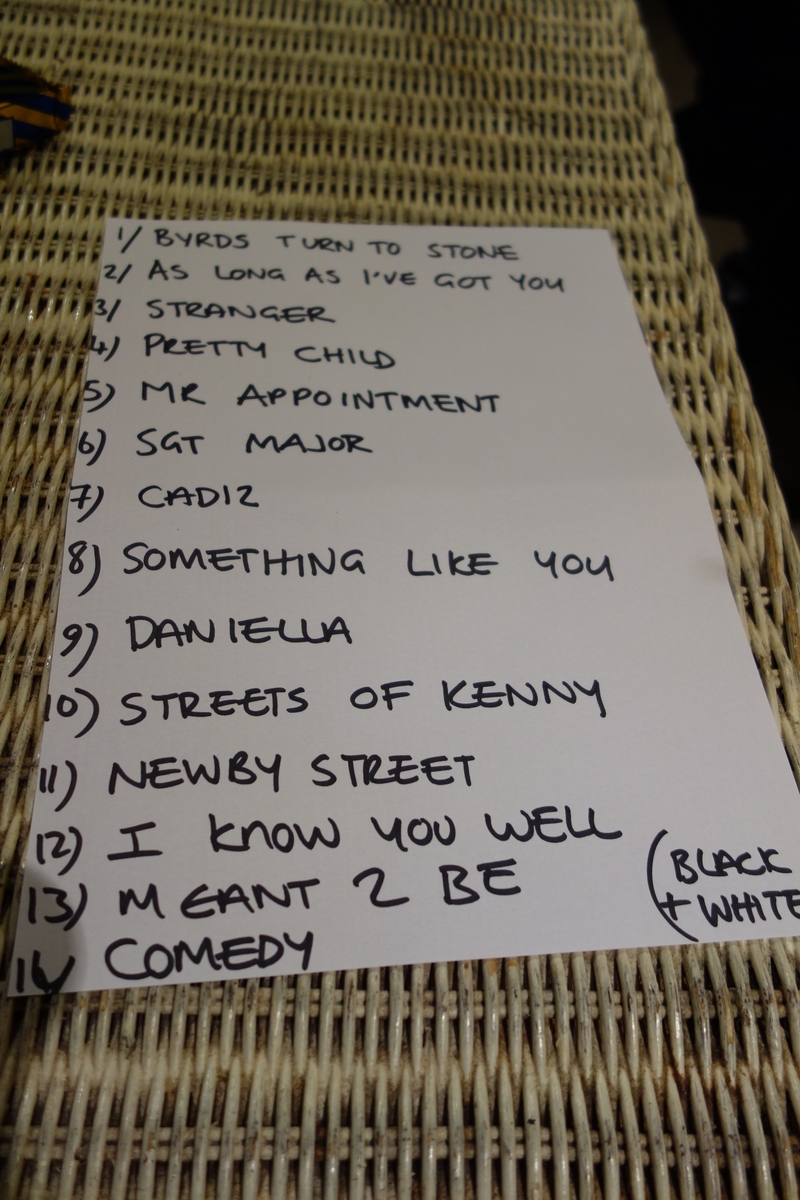

In Glasgow, for a performance a fortnight ahead of the album release, there, too, was the sense of a line being drawn. Nothing from Adiós, instead an electrically charged run through the archives.

Oran Mor, in Glasgow’s West End, is typical of the venues Head chooses to perform in, a former church whose intimate auditorium is packed with fans who goad him good-humouredly: “Got any eccy, Mick?” Briefly puzzled, he asks a man at the front, “what’s eccy?”

Ecstasy. “Oh, yeah,” he grins, patting his pocket. “Always packin’.” Ever the Kenny lad.

He’s the canny lad tonight, the Scottish branch of his supporters club every bit as enthusiastic (“WHAT. A. SONG!” someone shouts at the conclusion of the mariachi-rich Meant To Be) as his hometown crowd.

He rewards them with the best of Shack and more: Cadiz, Comedy, the achingly beautiful Something Like You and Streets of Kenny, the latter his biographical, uncompromising, unsettlingly rousing anthem to the desperation and elation of addiction in late 1980s, smack-addled Kensington.

Earlier, he recalled being quickly disabused of his romanticised view of heroin. “The honeymoon period’s too short to really develop. You end up actually writing about getting it instead of what it does to you. After a couple of weeks you are taking it just to feel normal and that’s the beauty and the romance gone right out the window, Thomas de Quincy’s just a dream, a lie down and an opium pipe.”

In good shape, he looks well, he’s lost weight. One young woman, registering the absence of fat on his face noted, “It’s got cheekbones!” with typical Liverpool directness. “Compliments,” notes Head, “came in various guises”.

Making the album allowed him to stay "sane and focused, getting my life back on track, to turn it round and be here sitting with you here, for example, and get back that connection with my family and kids, which is the most important thing”.

Of family, he says: “The love is always there, it’s never going to go away, it never does, but we see a lot more of each other, there’s a lot of positivity.”

And on gigging: “I massively prefer it now because you can actually see the appreciation of people who are there to see you. I applaud the crowd because we’re all in it together and a lot of them have been there since day one and it’s more than just coming to see some fella they know from Kenny. A lot of them feel like they’re part of it, which they are in my eyes.

“One of my things when I stopped drinking was not going round to everyone I’ve fucked off because I’d be there still, now. But I thought on the album I’m going to thank everbody, no big deal, no big like ‘I’d lke to thank the Oscars Committee’, just a thanks across the board.

“Some people turn round and say, ‘do you know what, it wasn’t that bad’, and you go, ‘listen, I fucking know it was.’”

Another day. Over cappucino at the monster-sized Tesco Extra in Park Road (“we call it Tesco Airport”), a hop and a skip from his home, the talk is of blackmail and paedophilia, subject matters for Sunny Vale, the holiday camp setting for his “fairly well formed” screenplay set across three decades. “It’s the opposite of Hi-de-Hi!” You don’t say.`

Then there is his return to France, where he and she will “just drive around for a bit, live for a few months, a bit of writing. Pascal (a French graphic designer and fan who creates artwork for Head’s record label) is organising a gig for us in Paris. It’s complicated but he’s on it.”

His new favourite thing is the piano. “Nina from the band gave it to me. It’s by the front door, it’s so big and heavy I can’t go past it without playing it.” A piano-based album is planned, with entirely new songs and Head on the ivories.

For Matt Lockett, Shack fan turned de facto manager of the REB, and co-founder, with Head, of Violette Records, all this is music to the ears.

Lockett has done much behind the scenes to facilitate Head’s music but, he says: “I met Mick the other day and he was happy, excited about his music and the band, enjoying his life and looking forward to the future. That’s enough for me.

“He says that he has enjoyed making this record like no other. He seemed genuinely saddened when each of the musicians left after completing their parts – and he finished wanting to do more.”

Through nearly 40 years of making music, the songs have never stopped coming, even “when I was a junkie”. And as Lockett observes, unlike many contemporaries “the quality of his records has never once wavered”.

Has music saved him? Head is emphatic: “Yes, completely, definitely. I feel for people who are coming into stopping drinking or drugs – you do need something to fall into and I was lucky to have the guitar.

“I’ll always say that. Without the guitar I’d probably be fucked. It’s a piece of wood in the corner. It’s not much but it’s something.”

*Adiós Señor Pussycat, Michael Head and The Red Elastic Band, released Friday 20th October on Violette Records.