YOU know it's going to be a good day when one of the country’s most experienced chefs sets off for Liverpool, at 6am, from his house in Bristol, carrying a curry he has made in his own kitchen.

Goat curry.

Confidential had idly lamented, last week, how, apart from Ragga’s, the odd specials board and the Africa Oye weekender in June, there was not enough goat curry going around Liverpool.

Lean, free range, deeply different to lamb or beef, and the one time munchies must-have in every shebeen in Liverpool 8; just the thing to go with a crate of Red Stripe and some Judge Dread. Come on!

Then today this shows up: a bubbling Dutch cast iron pot. Heavily spiced marinated meat, carrot, potatoes, coconut, red pickled onion, rice and peas, brought not from Trinidad but Temple Meads.

Its creator, Colin Scott, is telling how he started his career at 16 alongside another school leaver, lifelong chum Jamie Oliver. The training ground was Mr Oliver Snr’s pub, The Cricketers, in Saffron Walden, Essex.

After many adventures, Scott is now the daddy of food for Turtle Bay, the Afro-Caribbean restaurant concept that plays with fire - to the appreciation of chilliheads across the UK.

Colin Scott: 'A chef can cook any cuisine well, as long as they understand the four tastes and how they work'

Colin Scott: 'A chef can cook any cuisine well, as long as they understand the four tastes and how they work'Turtle Bay opens to the Liverpool public this Friday, in Victoria Street, its first venue in the city, in what is now called “The Produce Exchange”. Another branch opens in Hanover Street next year, and Scott, a font of food knowledge, is here to give the army of kitchen staff the final drill.

"There's a lot riding on Liverpool," he says, "We've been mad keen to come here for ages, the big Afro Caribbean community, the nightlife. Everyone has Liverpool on the radar."

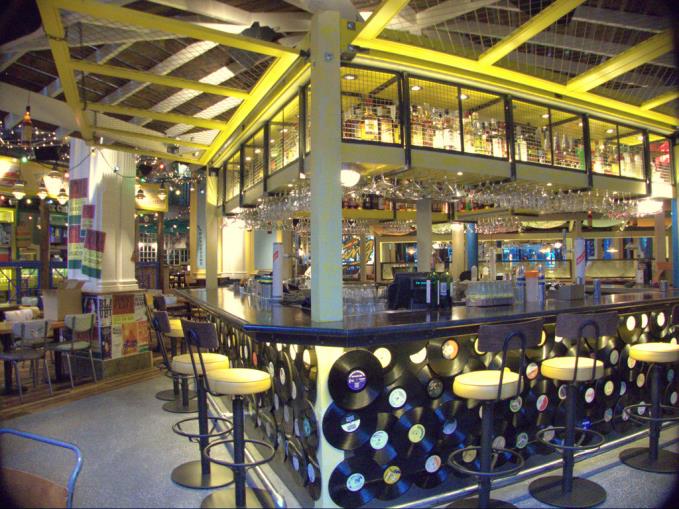

With its rum cocktails, murals of Bob Marley and faded timbers of yellow, blue and orange, Turtle Bay wants punters, via CAD, to live the Reggae Sunsplash dream everywhere from Milton Keynes to Newcastle.

However agreeable it all looks - and it is very easy on the eye - Scott insists the food won't bow to the traditionally timid, British high street palate.

First look inside Turtle Bay, Liverpool

First look inside Turtle Bay, Liverpool

He is pulling apart a scotch bonnet chilli, "the only sort we use. On the Scoville scale of heat of one to ten, these are a nine," he declares. "If people talk talk about a night out in Turtle Bay and say, 'blimey the food was bloody hot in there,' I know we've done it right. I'm addicted to hot food. Aren't you?"

West Indian grub is a world on a plate, influenced by the Spanish, British, West African, Portuguese, Chinese, French and the Dutch who all rocked up in the wake of Columbus. Not forgetting the swathes of Indian workers who arrived much later, bringing cumin, cloves, fenugreek, fennel and turmeric, making Jamaica famous for its curries today.

Elsewhere, spicy, vinegary Escoveitch fish arrived via Spanish Jewish settlers, The English could only manage pasties. Not to worry: throw in a few No 9 chillies and sweet potato and voila! glammy Jamaican patties.

Pride of place is the Caribbean repertoire is, of course, jerk, the word referring here to the movement of turning highly spiced chicken, pork and seafood over flames. Imported by shackled Africans in the darkest hours of slavery, today you will find jerk happening over pimento wood fires on the idyllic beaches of the islands at sunset. Or, in our case, in Smithdown Road cafes.

Hot jerk sauce anyone?

Hot jerk sauce anyone?Seeing as we are all here it would be silly not to talk Scott into rustling up a whole half jerk chicken for information purposes. While he does so, he is scrutinised by the whole kitchen including the gaffer, a Polish chef called Magic, now on his third Turtle Bay.

Scott is recalling how he launched the first Jamie's Italian for The Pukka One who, he admits, has suffered something of a backlash of late in his sugar tax efforts.

"And yet, he really does mean all the stuff, the campaigns," he says. "Jamie absolutely hates to see people eating rubbish food. It kills him."

Wait a minute. Jamie's Italian? Now Turtle Bay? Apart from the tenuous Message to Rudy link, it's a bit of a leap.

"Nah, a chef can convincingly cook and teach any cuisine well, as long as they understand the four tastes and how they work: sweet, sour, salt, bitter and, the fifth, the (addictive) umami, says Scott as he rescues the molasses-covered chicken from the flames, ladles over some hot lava, then an orange chutney and nails his point.

But back to the goat curry which Scott makes no bones about, either literally or figuratively.

"It doesn't have bones in it, how you would expect to find on a Jamaican food stall," he says. "That works best when you pick it up, use your fingers to eat it. We tried it early on. But people were unwilling to use their hands in a restaurant setting. And it's a little awkward to get round with a knife and fork.

"We call this Our Goat Curry and it's gone through 14 incarnations to where it is today. We are the only major restaurant making it at all.

With a flourish he removes the lid from a deep enamal pot, familiar, fragrant spices exploding into the air.

You've come a long way, kid.

Goat curry ends a journey of 180 miles

Goat curry ends a journey of 180 miles