The band from the Deaf School’ were at first a random line-up of rotating frontmen and women, eclectically dressed, preferring skits and wit to musical skill or singersongwriter sincerity. Joining them was akin to reinventing yourself as a comic character. Most recruits were art students, some were college staff. It’s quite possible that some simply wandered in off the street. They were all over the place. Clive Langer was driving the tramcar, but his ad hoc band still had a touch of the Frankensteins.

Chapter One: Tramcar to Frankenstein

The Surrealist Republic of Liverpool 8

High on a city hill is the Anglican Cathedral of Liverpool, in brown square-shouldered loneliness like a double-crossed gothic gangster, wondering where its world went. But climb to the top of that tall tower and look down. See all the little dramas of love and lust, riot and poverty, played out by those tiny figures in the streets, chasing their insect destinies.

Up here we can see for miles. Buffeted by winds from the Irish Sea we try to make sense of Liverpool. Well, we try. What are those? Giant iron turbines rotate idly out west in Liverpool Bay. Grey distance, Ireland behind. Beyond that, next stop Pier 92, West 52nd Street. On the skyline a vast spread of bruised blue Welsh mountains. But nearer, two silver strips of river, the Dee and the Mersey, defining that weird peninsula the Wirral, mystically known as ‘across the water’. We see pony-owning villages and dying publand proletowns.

Back over here, at the water’s edge two Liver birds perch above a tangle of city streets built for warehouses and whorehouses and counting houses, and everything needful for an enormous seaport.

If Liverpool is not exactly England,

then Liverpool 8 is not exactly Liverpool.

Turning to look inland we see some vaguely green horizon. Travellers from this eastern region speak of a land called Lancashire. They describe the mighty city of Manchester. Perhaps they are right. Liverpudlians are not so sure.

Whatever. Now look down below. Right down at Gambier Terrace, regal as a queen and full of secrets. At her feet, the vertiginous cliff-face of St James’s Cemetery, a mossy necropolis in the void of a former quarry, dug in the sandstone spine that separates Liverpool from England. North along that spinal ridge sits Hope Street.

Here, in fact, is the much-mythologised district of Liverpool 8, whose name is more than merely a postal zone. If Liverpool is not exactly England, then Liverpool 8 is not exactly Liverpool. In the city’s psychic geography it came to represent two worlds outside the Scouse mainstream, worlds we can roughly summarise as ‘foreigners’ and ‘white layabouts’. If you’d grown up locally with any inclination to la vie bohème then you were steadily drawn here on both accounts. It offered difference, a thrill of the unfamiliar and perhaps a slight dash of danger.

Handsome old precincts still give Liverpool 8 the look of a slightly battered Bloomsbury, and it was often compared to that area, especially when the stolid merchants who built it made way for artists and poets. The look was also reminiscent of Dublin, compounded by the various corner pubs whose tobacco-browned rooms might host the repartee of literary wits or the mournful bellowing of a sentimental drunk.

Numerous ethnic communities also made this singular arrondissement their own. Dubious late-night joints attracted curious adventurers. And slowly a Kingdom of Outsiders took form here. John Lennon at the art college, and Paul McCartney at the grammar school next door, each sensed something wonderfully exotic on their doorstep and hurled themselves at it.

And writers always loved Liverpool 8, with its abundance of raw material – professorial flotsam, red-light jetsam – and the contrast of prosperous facades with shadowy backways, and ruined stables whose last horses bolted a hundred years ago. Beryl Bainbridge constantly re-lived her local upbringing, weaving in the legend of Adolf Hitler’s lost years in Stanhope Street. Her friend and fellow novelist Alice Thomas Ellis wrote of passing an alley and hearing a frightened girl’s voice: ‘Let me go and you can have yer ten bob back!’ That is the bleakest haiku of Liverpool 8.

Deaf School grew from this fertile soil. With a pungent identity of its own, Liverpool 8 would draw these dozen young people from all corners of Britain and propel them into reckless, life-changing decisions.

********

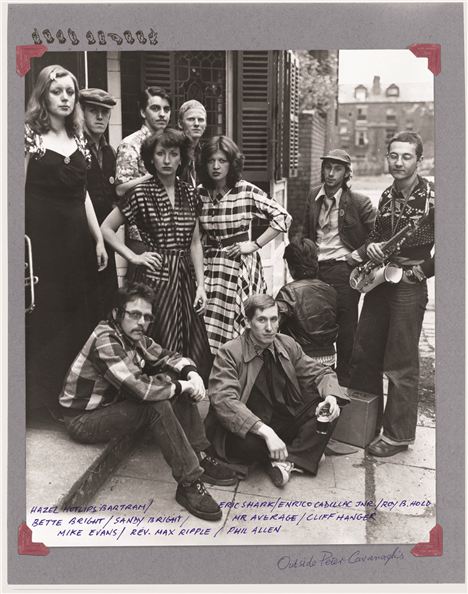

Deaf School Outside Peter Kavanaghs

Deaf School Outside Peter Kavanaghs

********

In autumn 1973 the new academic year brought to Liverpool a London boy named Clive Langer. He was already, in some ways, a typical product of the art school/ pop music interface.

Born on 19 June 1954, he’d taken his one-year foundation course at Canterbury, attracted there by the town’s musical reputation for brainy, jazz-inflected rock acts such as Caravan and Soft Machine. The latter band featured a particular hero of his, the drummer and vocalist Robert Wyatt.

Canterbury’s art college was also home to a tutor named Ian Dury, destined for pop stardom with the Blockheads despite his relatively advanced age and the pronounced limp he’d acquired through childhood polio. ‘I remember I opened the door for him in a corridor once,’ says Clive, ‘and he was pissed off, because he was hobbling about and it was as though I was taking the piss out of him.

But I was just trying to be gracious.’ Dury’s band of that time, Kilburn & the High Roads, were frequent Canterbury visitors and their musicalstyle, eclectic, rough-edged, theatrically presented by a sprawling line-up who dressed in artfully improvised jumble-sale clothes, would make a deep impression on the teenage Langer. After Canterbury he enrolled at Liverpool, largely unaware of the Liverpool 8 scene but certainly conscious of the Lennon connection. ‘I chose my art colleges because of the bands that were there.

I wasn’t that interested in art, I was more interested in music. Lennon was my favourite as a kid. I was in the cloakroom of my primary school, singing “Twist and Shout”, screaming my head off in front of my mates.

In fact if I’d known about the Dissenters I think I would have called Deaf School the Dissenters. It would have been a good name.’ Growing up in North London his young neighbours included future members of Madness.

As early as primary school he played in a Saturday morning band at the Swiss Cottage Odeon. Then, at his grammar school, William Ellis in Highgate, he was inspired by Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson to study the flute: ‘I failed my Grade 3, which is the first one you can take. I wanted to play blues flute. I didn’t want to learn music. I’m not good at reading music.

But I’m smart enough to listen, and to know what I want.’ Soon he was in a new band, with his schoolmate, the future film-maker Julien Temple. ‘Basically,’ Clive explains, ‘I’d just been obsessed by bands since I first heard the Shadows.

Suggs gets upBecause of this obsession, I just knew I could get into gigs, it didn’t matter if I didn’t have a ticket, or I was too young, there were ways. We could bunk into anything. I’d go to loads by helping the band, like at Klook’s Kleek [a club at the Railway Hotel, West Hampstead]: Family, John Mayall. Led Zeppelin I saw on their first tour when they just did some pubs. Like a blues band on speed, quite punky, but later they got a bit grandiose for me.’

Suggs gets upBecause of this obsession, I just knew I could get into gigs, it didn’t matter if I didn’t have a ticket, or I was too young, there were ways. We could bunk into anything. I’d go to loads by helping the band, like at Klook’s Kleek [a club at the Railway Hotel, West Hampstead]: Family, John Mayall. Led Zeppelin I saw on their first tour when they just did some pubs. Like a blues band on speed, quite punky, but later they got a bit grandiose for me.’

With Julien Temple, he went to a Wembley TV studio for the filming of the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus. ‘We’d just hear that something was happening and we’d go for it. By the time I was in the sixth form, because of this band I was in with Julien, it opened my ears to John Coltrane, and Weather Report and the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Rock and jazz were mixed up for me after Miles Davis’s performance at the Isle of Wight.

In fact I was there, and saw Hendrix too.’ Langer’s cool determination could well be inherited from his father, a Polish Jew who, alone of his family, escaped the Nazis and settled in London via spells with the British army and the Polish air force.

He married an East End girl, became a businessman and in time acquired a couple of hotels in Bloomsbury, the Gresham and the Crichton, which would often serve as Deaf School’s base in the capital.

Deaf School’s inception can probably be dated to the art school’s first day of term in 1973, when Clive Langer noticed another new student who might make a potential ally. ‘I thought, Well, he looks interesting, he’s the only bloke here with slicked-back hair and tight jeans. Everybody else is boring.’

The young man who caught Clive’s eye was Steve Allen, the future Enrico Cadillac Jnr. Exactly the same thing had happened there sixteen years earlier, when Bill Harry spotted John Lennon, teddy boy rebel among the academic dowdies.

l**Paul Du Noyer's book, Deaf School, The Non Stop Pop Art Punk Rock Party, £15.95 is published by Liverpool University Press on Monday October 21.

l**Paul Du Noyer's book, Deaf School, The Non Stop Pop Art Punk Rock Party, £15.95 is published by Liverpool University Press on Monday October 21.

***Deaf School will be playing a very special celebration concert to launch the book at East Village Arts Club, Seel St, Liverpool, next Saturday October 19. Special advance copies of the book will be on sale and the last batch of tickets for the gig itself can be bought here