“PEOPLE with no sense of humour have done a huge amount of damage in the world. Can you imagine Stalin telling you a joke?”

Terence Davies, maker of some of the most anguished films ever to have seen the dark of day, is pondering this over breakfast eggs - “sunny side up” - in a Castle Street restaurant.

Stalin might have had his lighter moments, I venture.

“Yes,” he bats right back, “did you hear the one about the Englishman, the Irishman and the Ukrainian?”

Not for the first time, the master of tragedy is displaying his mastery of the witty riposte, and he has had plenty to smile about of late.

'There were some men working in there making a wall, and they just had jeans on. No shirts.' He pauses. 'I didn't know what it was called, but it ruined my life. Just like that.' He clicks his fingers

Davies has been in town for the last nine months, and latterly in Cannes where his shoestring documentary, Of Time And The City, one of three cinematic commissions for Liverpool 2008, has been going down a storm.

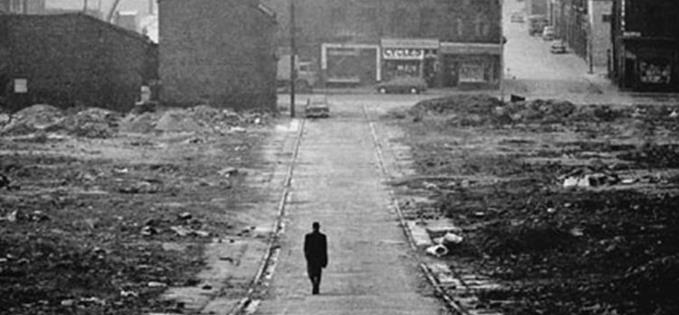

With its archive, monochrome footage (“we've seen every bit of film ever made about Liverpool,” says producer Roy Boulter) juxtaposed with fresh shots of the modern city, a wildly varying soundtrack and Davies' own Noel Coward-esque narration, Of Time And The City is poised to turn the Kensington-born director into the comeback kid after years in the cinematic wilderness.

It has received rave critiques on the Riviera, with Time Out (to pluck just one from the posy of plaudits) declaring it “some kind of masterpiece” and the team behind it are still having difficulty taking it all in.

But Davies, maker of the autobiographical Distant Voices, Still Lives and the lesser known Trilogy, also about his Liverpool upbringing, reveals that as far as his birthplace goes, this "eulogy" is positively his final act.

"It is a farewell,” says the one-time bookkeeper (he left to find films and fortune in 1973). “A lot of my family are dying. The ties are becoming looser and looser.”

He describes new Liverpool as an alien landscape, stays with his sister in Whiston, and yet “I always think of home as 18 Kensington Street, no matter where I am. From the ages of seven to 11 I was ecstatically happy there. For those four years, I was literally sick with happiness.

“Then it went,” he adds flatly. “And I've never been happy since.”

Davies is full of these stark and frank assertions. His traumatised childhood is well documented. One of nine children, his brutal father (played by Pete Postlethwaite in Distant Voices), a rag man, subjected his family to regular beatings. He died when the young Terence was starting to think he could cope with no more, and all the lights instantly went on in his world.

“At seven, my father died and we began to live,” he says simply. “My mother began to get her hair done. She looked so beautiful when she did that.”

Around then, Davies also ventured into the portals of the local picture house for the very first time: The film? Singing In The Rain). “It was a huge revelation,” he recalls. “I remember absolutely being bowled over and I couldn't stop crying.

“And my sister said, 'what are you crying for?' And I said, 'Because he (Gene Kelly) seems so happy.' And for the first time I thought you could be happy. When my father was alive it was utter misery because he was psychotic. You were terrified all the time.”

Then just as abruptly, when Davies was 11, the lights went off again.

Davies recalls: “That summer between finishing primary school and starting secondary school was very hot and there was a big garage at the back of the street where I lived, called Smettles. And there were some men working in there making a wall, and they just had jeans on. No shirts.

He pauses. “I didn't know what it was called, but it ruined my life. Just like that. He clicks his fingers.

Almost as afterthought, he adds: “Then when I went to secondary school (Sacred Heart) I was beaten up every day for four years, which just destroys you.”

Davies' new found homosexuality did not rest easily alongside his Catholic upbringing. He is celibate and calls his sexuality a curse.

“I'm not religious. I don't do sex. I don't do rock and roll and I don't do drugs. So what's left? Typhoo?” he laughs.

“I'm an absolute atheist, but I can't give up what was instilled in me as a child. It was the Jesuits who said give me the child and I'll show you the man, which is really sinister. You can't get away from it. I examine my motives all the time. You get fed up with it, this conscience constantly saying, 'have you done the right thing? No you have not done the right thing.'

“But the penny didn't drop about God until I was 22, for God's sake. With everyone else it was 13. And, at 22, I thought 'Oh, it's a lie. Thank goodness!'"

Davies doesn't subscribe to the view that what doesn't kill you makes you stronger: “That was said by Nietzsche and he suffered from syphilis, so I'll take it with a pinch of salt,” he says with another camp guffaw.

“I think it does something far worse: it fosters bitterness and there were times when I did feel terribly bitter. And that's no good. You just get eroded.

“One day, about five or six years ago, I thought: I don't love my father, because I never could, but I don't hate him any more. It was extraordinary, I can tell you.”

As much as he despised his father, Davies adored his mother, and it was a chance photo-shoot of her, not long before she died, that was to ultimately lead to Of Time And The City being made.

Sol and Roy of Hurricane Films

Sol and Roy of Hurricane FilmsPhotographer-turned-film maker Sol Papadopoulos, who runs the Hope Street-based Hurricane Films with Roy Boulter (drummer in The Farm and a successful TV writer), called Davies up last year and asked him if he wanted to enter North West Vision's Digital Departures competition.

“He said: 'Do you remember me?' and I said: 'Of course, you took some very beautiful pictures of my mother, which I still have. Although she was ill, I still think they are beautiful.'”

But Davies said he wasn't interested in a proposed work of fiction. “I've done fiction,” he says. “I said what I would be interested in doing is a film about the Liverpool I knew, contrasting with Liverpool as it is now. And that's how it happened.”

Next stop for Of Time And The City is the Edinburgh Festival. Next stop for Davies, who admits his view of life is "intrinsically tragic", is a comedy. Finally. It's about a ménage a trois at a fashion magazine.

“I do love to make people laugh, and I do love to be made to laugh, because it's life affirming.”

Amy's Back to Black strains in the background, and Davies tells me his life has never been a success. “I knew in my heart that it would be a struggle. Even as a child I was aware that moments of absolute ecstasy were going, even as I was experiencing them.

"I need help," he says, "lots of help."

Then with a grin. “That's what my therapist says anyway.

“And even he hates my father now.”

Of Time And The City plays Liverpool in October and goes on general UK release in November.