'There was something about his mere presence that instigated events and made change seem possible' - Bill Drummond

HE started out with ambitions to become an opera singer but instead of The Great Caruso, Allan Williams became the Great Carouser.

He was The Man Who Gave The Beatles Away, Singing Dolphin, founder of the Blue Angel and Jacaranda clubs, and, many would say, a charmer and a chancer.

Without Allan Williams, Liverpool would be a completely different place. So would the history of western culture in the second half of the 20th century

But Williams, who left on life's last train out of 2016, was something else. His seismic effect - intentional or otherwise - on Liverpool and, by turn, the world as we know it, deserves serious consideration and recognition.

Whether that happens is another matter.

Lew Baxter, who wrote his second volume of memoirs, Fool On The Hill, in 2003, says Williams was “undoubtedly one of the most colourful and charismatic, if often disparaged, figures in the seemingly never-ending circus of the Beatles”.

Artist and writer Bill Drummond told Liverpool Confidential : “Some people make a difference. Allan Williams was one of those people.

“Without Allan Williams Liverpool would be a completely different place. So would the history of western culture in the second half of the 20th century.”

Born in 1930, in Litherland, Allan Williams was the product of a pollen which had drifted in on the Welsh breeze and settled in the petri dish of early 20th century Liverpool.

His father, Richard, said to be a descendent of Owain Glyndwr, was a corporation building inspector and joiner. Allan never knew Annie, his real mother: she had died while giving birth to twin sisters who also failed to survive. Instead, for years, he thought Dick’s second wife, Millie, was his mother.

Evacuated to North Wales during World War II, Williams returned to become a plumber at the age of 15. But pipes of a more physical kind were his strength - a glorious tenor voice which led him to sing with the Joe Loss Orchestra, the D'Oyly Carte and with the Bentley Opera Society.

It was there he met Beryl Chang in 1953. She would later become one of the most formidable and successful landladies and business women in the city, but not before being wooed and wed by Williams in 1955.

It was the start of a long and eventful relationship which would earn both of them the disapproval of their respective Sino-Welsh families.

Away from Liverpool they encountered no such taboos and the carefree young couple would often take off around 1950s Europe, hitch hiking, hosteling and sampling the coffee bar and jazz club scenes of Paris.

“We loved to go to the Saint Michel jazz clubs and see these youngsters in cellar clubs having fun. It was not possible in Liverpool then, but I thought it was a great idea,” Williams later said.

23 Slater Street, the Jacaranda club, did not need to sell booze to be a success, it made money out of Pepsi by the gallon.

The differences didn’t end there. Its house band were fresh from the Windrush and the shebeens of Upper Parliament Street, a Trinidadian steel calypso ensemble led by Harold “Lord Woodbine” Phillips who would become Williams’ early partner in capers. “I didn’t think they would last 10 minutes, they lasted 10 years!” said Williams.

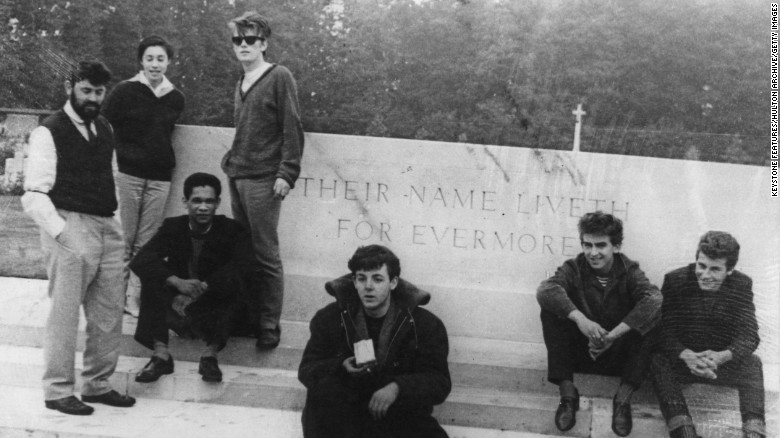

Quickly the Jac became a haunt of Liverpool Art College students who, along the way, were enlisted to paint the cellar. One of these volunteers was Stuart Sutcliffe. Stuart Sutcliffe brought his friends from his other life which involved toying with a bass guitar in a fledgling beat group. Those friends were John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison.

What followed was a whole chain of events that changed history but there was no compass, no road map - at least none that Williams had drawn. His initial idea of the bright lights for the Beatles involved a regular gig backing a Mancunian stripper called Janice in a Garston social club.

Nor was there any real strategy when he, Beryl and Woodbine drove the group, with newly enlisted drummer Pete Best from Liverpool to the red light district of Hamburg, the place where members of the calypso band had fled, sending back stories of good times.

And no one could foretell that the teenagers would become the tightest band on the Reeperbahn, one of the toughest streets in Germany. Nor that upon their return to Liverpool, kitted out in leather trousers and attitude, they would tune up and turn on every screaming girl in the city; not to mention one restless young Whitechapel record shop manager whose greatest gift was a line in London gab.

Williams had played his walk on part, extraordinary stuff had followed, and it didn’t end when he “gave the Beatles away” - in reality a dispute over some unpaid commission in Germany.

Drummond says he first met Williams in 1975 when, as newly appointed master carpenter at the Everyman, he rented theatre digs from Beryl in an unlovely part of Kensington.

Over the next eight years, he says, he had four very different but meaningful encounters with Williams, which he describes as “departure points”.

He says: “Allan may never have been an obvious visionary and apart from his tenor voice I was not aware that he contained any obvious form of creative talent. There was something about his mere presence that instigated events and made change seem possible."

Williams, who already had his first autobiography out, had been introduced to the late, great theatre director Ken Campbell via Peter O’Halligan. His vocal talents were seized upon, earning him a place in the Ken Campbell Roadshow, an ensemble that played pubs in places like Kirkby and Cantril Farm.

He was then cast, alongside the likes of Bill Nighy and Jim Broadbent (Drummond was the set designer) as Howard the Singing Dolphin in Campbell’s 1976 production of Illuminatus! which began life in Mathew Street’s Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun before transferring to the National Theatre.

Cut, then, to the tantalising notion that Liverpool - Ginsberg’s proclaimed “centre of the creative universe in the 1960s” - might never have had the courage to reclaim its place if it hadn’t been for an encounter of a third kind, on Mathew Street, “the place where it all began” a year later.

“It was May 5, 1977," says Drummond. “Clive Langer, Phil Allen, Kev Ward and myself were sitting having a quiet pint in the Grapes. We were planning to go and see The Clash play, two doors up, in Eric’s. Then in walks Bob Wooler and Allan Williams. They get their pints and sit down beside us.

“Bob Wooler’s legend was and still is legend. He had been the DJ at The Cavern. It was him that turned the ‘Hi-fi high and the lights down low’ for the generation before us. Bob Wooler always had a twinkle in his eye.

“Conversation ranged far and wide,” he said. “And one of the topics that they were most insistent on pursuing was that we – Phil, Kev and myself - should form a band. The fact that we had never been in any bands before, they saw as a positive plus.

“Clive Langer was then the leader of Deaf School. Kev Ward designed their record sleeves and Phil Allen was the brother of the singer. The next morning Clive was leaving for an American tour with Deaf School. Allan and Bob told Clive he should let us use their equipment while Deaf School were in the USA as they would be hiring gear over there.”

Langer duly agreed.

“The next morning Kev, Phil and I wrote our first song," says Drummond. "It was called Big In Japan. We decided to name the band after the song. Others joined our band. And others formed bands in our wake.

“Without Allan Williams’ presence in The Grapes that evening, Liverpool would have continued to struggle under the shadow cast by The Beatles and a whole generation of bands would never have happened.”

Tales of hellraising and barring out from pubs are legion, as are the anecdotes from the Wooler-Williams days (the two had founded the city’s first Beatles conventions).

Baxter witnessed an incident in the Mathew Street Grapes, in 2002, when Williams (who by now had formed a later life relationship with the former Mrs Wooler, Brian Epstein’s secretary Beryl Adams) was attempting to flog off a shoebox, allegedly filled with Wooler’s ashes, to some Japanese tourists.

“He was a fabulous raconteur, wit and richly amusing company on most occasions - until the demons began spitting fire once the drink was ‘on him’."

Yet when he wasn’t in his cups, or guest speaking at one of the hundreds of Beatles conventions around the world, Williams was a shy, mild-mannered man whose soft spoken cadence owed more to a Bootle elocution teacher in childhood than to the Valleys.

It was this version Liverpool Confidential recognised last May, at Liverpool Town Hall, where he was being made a Citizen of Honour for the key role he had played in the city’s Beatles industry, now worth £80m a year.

By now living in a Dingle nursing home, Williams gamely played for a picture for us on the famous balcony where the Beatles appeared before 100,000 fans in 1964.

He quipped: “It is not only the first honour I have received, it’s the only honour."

Perhaps not. Drummond cites a chance meeting with Williams in a Boston lift, in 1983, which caused him to give up managing Echo and The Bunnymen with whom he was on tour.

“He told me if he had not given The Beatles away they would have never done a thing. It was the act of giving them away that made them happen. It was later that night I decided that if I really wanted Echo and The Bunnymen to become the second greatest band in the world I should give them away.”

He added: “As yet I am not sure if the plan is going to work out.”

“There was a stillness, a melancholy about Allan,” says Baxter. “Sometimes he had this thousand yard stare, and it was hard to break it, or to see behind it. He had had a troubled childhood which he never elaborated on, but said he recognised the same traits in Lennon, which drew him to him and the Beatles.”

Maybe that, or maybe because, in Williams’ opinion “all the other Merseybeat bands were as thick as pigshit”.

Does a clue lie therein? For despite the bemused delivery, one suspected there was too much going on inside Williams to tolerate the cold light of fools - of which there were many in his midst.

“Sure he was a rascal, with a waspish tongue when roused, but never really irascible,” Baxter says. “People like Allan Williams take up a big space in the world and enliven our lives. He’s now where he should be: amongst the meteorites.

“He once told me: ‘I could be regarded as the world’s biggest loser but then I look around and realise that actually I am one of the survivors. Me and Pete Best.’”

When, some years ago, the Daily Mirror ran a list of the 20th century’s biggest business blunders, Allan’s decision to throw away the most influential musical group in history, just as they were on the cusp of success, came bouncing in at a resounding second place.

He would frequently delight in the accolade - but only up to a point.

“I didn’t give the Beatles away,” Williams would spit. “I told them to fuck off.”

*Allan Williams, March 17, 1930 - December 30, 2016, is survived by Beryl Williams, son Justin and daughter Leah.