THE sub-title “Modern Master” might be designed to provide a patina of gravitas to the exhibition, but is Marc Chagall really in the same league as, say, Picasso, Braque and Duchamp?

Debateable. However, the purpose of Tate Liverpool's crowd-pulling 25th anniversary show isn’t about that.

I found myself comparing Love on The Stage

to Banksy’s early works. It was enchanting –

my highlight of the exhibition

It’s more about how Chagall managed to develop a deeply personal body of work which, though influenced by the succession of “ism’s” in the early part of the 20th century, maintained an individualistic and instantly recognisable style.

This retrospective (the last was 15 years ago) spans a good deal of Chagall’s work but concentrates on his early influences: namely his upbringing at Vitebsk and the time spent mixing with the Cubists and Fauvists in Paris between 1912-14.

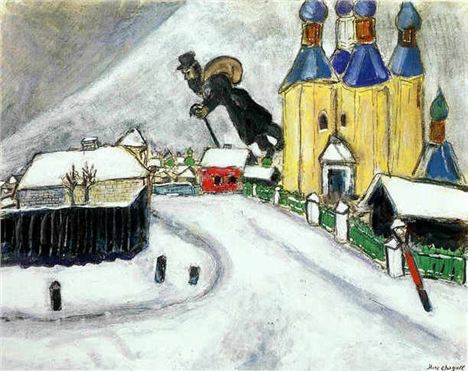

Perhaps more importantly, his deeply-held Hasidic Jewish identity became a central theme throughout his artistic life. This resulted in a yearning for self-expression which tended to echo Russian-Jewish folk-culture; in particular, his home village and almost Bruegelesque depictions of everyday life amongst the artisans and farm-workers.

Another recurring theme was the deep emotional attachment which found expression through the loving transfer of pigment to canvas. Love of family life, of tradition, of country, of dachas, farmyards and animals he knew from childhood.

Commentators may describe this as primitivism. However, it could be argued that he created something quite unique to himself – atavistic art in a modernist context. These Hasidic roots ran deep in Chagall’s world-view and he returned to them time and time again.

This was encouraged in his early training at the Zvantseva School of Drawing and painting in St Petersberg in 1907, where he first became aware of the Parisian trends in cubism and fauvism.

In order to fully immerse himself in this new creative dynamic, he set up his own studio at “The Beehive” in Paris in 1912, mixing with poets Cendrars and Apollinaire and showing his work at the Salon des Independents. It was a heady time.

Consequently, his paintings began to incorporate novel ways of representation but, importantly, not fully cubist as such. He did it his own way, stating “I detest reducing everything they depicted to mere geometry – I was seeking liberation”. Certainly, he felt part of this new wave of semi-abstraction but wasn’t a fully signed-up member of the cause-celebre.

That said, Parisian café-culture gave him the chance to experiment – in poetry for one, but also, figurative work and nudes, something quite novel considering his upbringing.

His Homage to Apollinaire (1911-12) is dedicated to his erstwhile compatriots including Walden and Cendrars. During this time, he discovered a new concept – orphism, promoted by Apollinaire and the Delauney’s as a means of “pure painting” which allows for imaginative [almost unconscious] treatments to follow through.

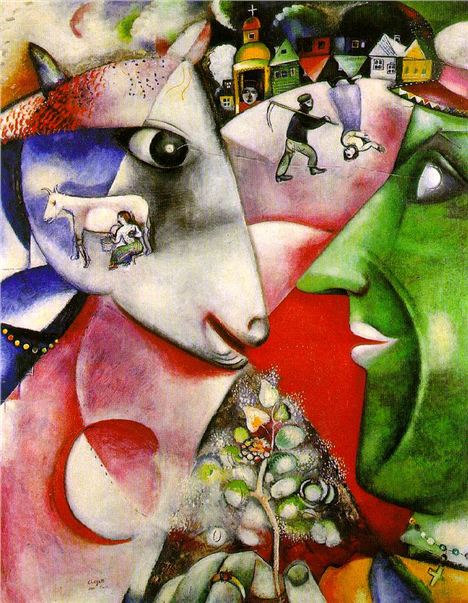

One work in particular, I and the Village (1911), is probably the most well-known and best example of Chagall’s work. It’s a synthesis of Yiddish folk-culture with strong fauvist abstractionism. There’s no particular narrative to hold it together, but the colours just spring out at you.

Notice the Tree of Life at the base and the floating woman in the background. Floating figures were to be a recurring signature throughout his career, perhaps signifying being in a state of dreamlike sleep. As he said; “If I create from the heart, nearly everything works. If from the head – almost nothing”.

Just as Chagall’s career was beginning to become established in Paris, the outbreak of the Great War prompted him to leave for Berlin and, soon after, to return to his homeland in Vitebsk. Not exactly the prodigal son, but certainly prodigious. Jewish-Russian themes predominate again and he underscores this period with reference back to his singular obsession with village life – not exactly a rural ideal but more rural surreal.

Surprising, then, that Chagall decided to throw his lot in with the post-revolutionary Soviets by being appointed “Arts Commissar” for Vitebsk itself where he was invited to establish the People’s Art College.

He hardly had the best credentials to merit the role and it would have caused a great deal of friction with his compatriots who considered him to be too avant-garde for the supremitist elite. Nevertheless, he stayed for a year before handing in his resignation. His involvement with the Theatre of Revolutionary Satire (I kid you not) mustn’t have worked in his favour, then.

By 1920, he found himself back in Moscow where he became closely involved with the State Jewish Chamber Theatre, including set and costume design. These murals and friezes form the largest pieces of the exhibition as “Chagall’s Box”, a custom-made reconstruction of its original presentation.

One piece, in particular, stands out…Love on the Stage (1920). It almost seems unfinished at first, yet there are some delicate subtle contour renditions with quite novel organza-type monoprints and filigree swirls. I found myself comparing it to Banksy’s early works. It was enchanting – my highlight of the exhibition.

Marc ChagallThe course of the next decade found Chagall back in Paris having decided his future lay in a more liberal European/American art establishment. It proved to be a wise move. His reputation progressed as critics and collectors alike became more aware of his unique contribution to the art world. By the outbreak of World War II, he’d gained French citizenship before finally settling in America.

Marc ChagallThe course of the next decade found Chagall back in Paris having decided his future lay in a more liberal European/American art establishment. It proved to be a wise move. His reputation progressed as critics and collectors alike became more aware of his unique contribution to the art world. By the outbreak of World War II, he’d gained French citizenship before finally settling in America.

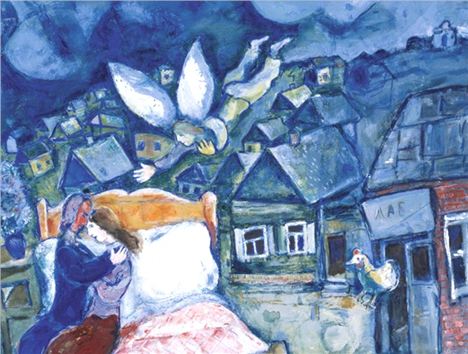

His work varied little as you can see in The Dream (1939). It’s all there – Vitebsk, the loving couple, the urge to reminisce.

Indeed, as he said himself, “Love helps me find the colour… I only have to apply it to the canvas. It is stronger than I am and it comes from the soul. That’s how I see life”

*Chagall: Modern Master, Tate Liverpool, Albert Dock, L3, until October 6, 2013. Adult £11.00 (without donation £10.00). Concession £8.25 (without donation £7.50.

Other events: Curator’s tour with Stephanie Straine, June 27, 5pm/Chagall: Modern Master with Rabbi Anthony Walker, July 11,5pm/Chagall Summer School, July 16-18, 10am-4.30pm