'In the days after the death of Pete Burns something grew in me. Some major sense of loss'. By Bill Drummond

WHEN I heard the news that David Bowie had died I felt little.

Even less when it was Prince.

When the news was announced, in June 2009, that Michael Jackson was dead, I think I thought – “Well of course.”

You Spin Me Round, by Dead or Alive, is great art. As great a work of art as anything else produced in the 20th century

As for George Harrison, there was a time he was my favourite Beatle and I had worshipped The Beatles. They are still the artists - in any sphere of the arts - who have had more influence on my life and work than any other. But when the news was announced that George Harrison had died of cancer, back in 2001, I just thought, “that is what happens to people.”

People die of cancer or heart attacks or strokes or any number of other things. Plenty of people in my extended family have died of such things. Many of those members of my extended family had died before their three score years and ten were up. Why should pop stars be any different? And anyway they have had rich and fulfilled lives, so what's the problem?

When I was young, rock stars died at the age of 27 from drugs and fast living. It was part of the career path. When that did happen to someone close to me, and for whom I felt responsible, it was different.

It was a motorcycle accident and he had just become a father for the first time and was getting over his breakdown and life was mending and sorting. And then he had a motorbike accident. And he was dead. And the band played on, but never the same.

Not a month goes by without him being in a dream of mine. We talk about this and that. But motorbikes accidents happen to young men who drive motorbikes fast through the night. They know that is the risk and part of the attraction. Even young men with new baby daughters.

When I first learned that Pete Burns had died it wasn’t, in any big way, different. What Pete Burns had supposedly put his body through over the years, with all the nips and tucks, no wonder it responded with a heart attack.

What was he thinking it would do?

But in the next four days something grew in me. Some major sense of loss. No, that is not quite it, I have lost nothing personally. But his death has created some landmark in my own life. Like when Tony Blair first became Prime Minister and Tony Blair was seven days younger than me. From that point on, those running the world would be younger than me. This was a difficult thing to comprehend. Barack Obama was not just seven days younger than me, he was more than seven years younger than me. From now on this was going to be the way things were.

But Pete Burns is dead.

The day after the news broke, my very close friend and colleague since 1978, Dave Balfe, sent me an email and I quote: “Hi Bill - bearing in mind the recent sad news, I thought you might like this old photo that just popped up on Facebook.”

I don’t do Facebook so had not seen it. Had never seen it.

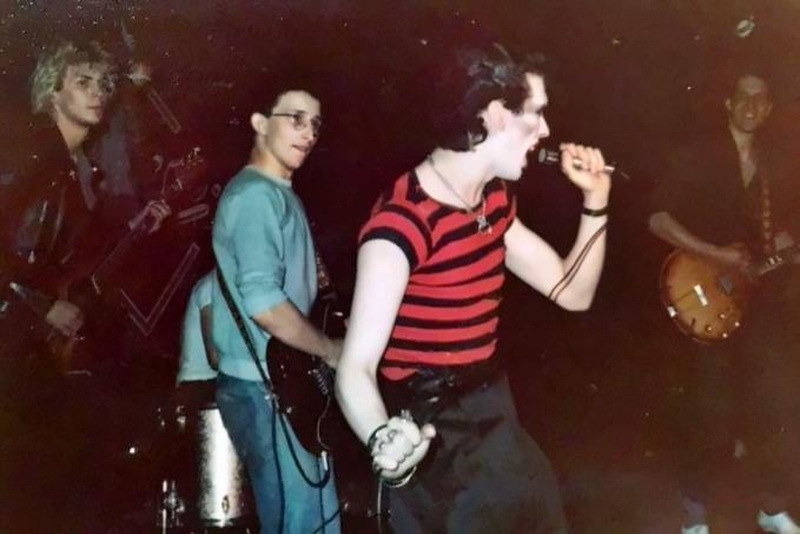

It was a photograph of Julian Cope, Ian Broudie, Budgie, Pete Burns and myself playing music together. When he first sent me the photo, I had no memory of what or when or why we might have all been playing together on the same stage at the same time. We were never a band. And although one cannot see much more than Budgie’s elbow, one knows it is him, as I am sure the others in the photo would concur. Who else would it be?

But over those next few days, memory upon memory came back to me. And as those memories revealed themselves to me, the effect of Pete Burns’ death grew in significance.

Pete Burns and I were never close friends but…

******

The trouble is I do not do nostalgia. I have no truck with it. But the further the late 1970s recedes, the more I know I was part of something in Liverpool. That something is a thing that does not happen that often and only in a few cities.

And whatever that thing was that happened in Liverpool in the last few years of the 1970s and the very early 1980s, I was very lucky to be part of.

The roots of whatever it was can be traced back to is down to whoever is doing the tracing. If the tracing was left to me I would trace it all back to a certain manhole cover, in Mathew Street, at the centre of where it was all happening. Nothing of significance occurred more than 100 yards from that manhole cover. And it can all be traced back to some point, in early 1976, when I first stood on the said manhole cover. But that is my version.

It was a scene, a classic scene, with its rifts and fall-outs and opposing sides and factions within factions. The thing is, at most, there were probably no more than 40 of us in this scene. And, of course, none of us knew it was a scene at the time. Scenes are only observed by those outside, who maybe want to be part of it. Those that were part of it could only know of its existence when it was all over.

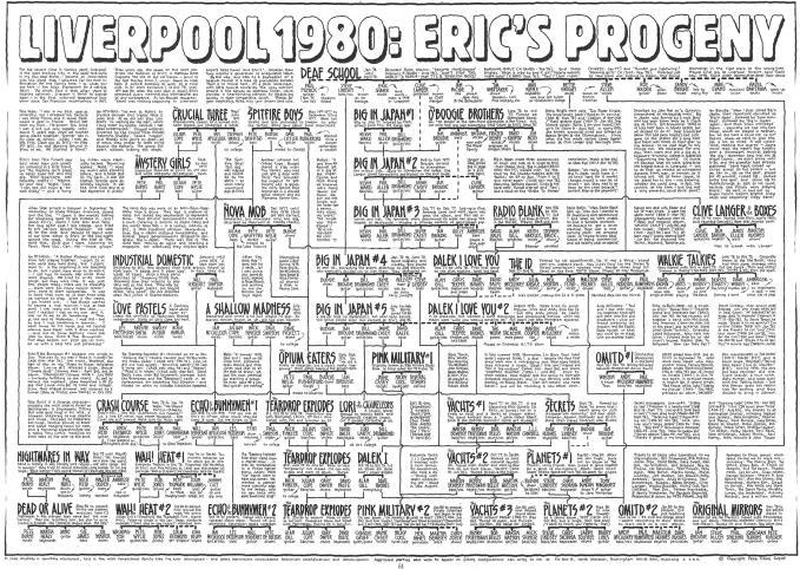

In 1980, the founding father of the greatest UK rock magazine ever, ZigZag, came to Liverpool to make and create one of his Rock Family Trees. This was Pete Frame. Pete Frame had been a sort of hero of mine in the late 1960s when I was a schoolboy into rock music. Pete Frame knew his stuff. He knew his shit. Or at least he knew what was shit and what was cool in a late 1960s sort of way. And here he was, in the spring of 1980, coming up to Liverpool and proclaiming we were a scene worth his while documenting in one of his, by then, legendary Rock Family Trees.

When it was done and published that August, I could not believe it. And I quote, and the reason why I can quote has nothing to do with my memory or even Google but because I have the original of what Pete Frame did framed on the wall in front of me: Liverpool is about to explode again – in the first unforced geographical rock boom since San Francisco mushroomed in 1967.

It never really did explode, like San Francisco but…

I want to rewind a couple of years, before Pete Frame arrived and proclaimed. I want to go back to the photo mentioned above.

On seeing this photo, on Tuesday, a photo I had never seen before, I did know the unseen drummer was Budgie and that we were playing on stage in Eric’s and it was sometime in the spring or early summer of 1978.

It was the person playing bass that was the giveaway. Budgie, Ian Broudie and myself were then in a band called Big In Japan. If it had been earlier than the spring it would have been our then bassist, Holly Johnson, playing.

It was in early spring that we had sacked Holly for turning up late to rehearsals and not seeming to take the whole thing seriously enough. The trouble was we all liked Holly and him and me lived near each other so we would get the bus into town together. But you can’t have someone in the band if they are going to turn up late.

The trouble was we all liked Holly and him and me lived near each other so we would get the bus into town together. But you can’t have someone in the band if they are going to turn up late.

So it wasn’t Holly and it wasn’t either of Holly’s replacements – Steve Lindsey or Dave Balfe, it was someone else. It took me a bit of time to realise it was a very young Julian Cope on bass. A Julian Cope before I knew Julian Cope proper.

I then realised that it was probably this Julian Cope that had instigated this performance. Julian Cope had already formed a band with Pete Burns called The Mystery Girls, with Pete Wylie on guitar and Phil Hurst on drums.

The greatest achievement of The Mystery Girls was to start a petition for Big In Japan to split up. Or was that The Nova Mob? Anyway, it was a band with Julian in. They proclaimed that if they got 1,000 signatures we would have to split. Of course they tried to stop us in Big In Japan signing the petition.

I look at the photo some more and I think. I vaguely remember how there had been a rift between Julian Cope and the guitarist in The Nova Mob, the guitarist being Pete Wylie.

I remember having a conversation with Julian Cope, some time around then, about the chord structure of The Kingsmen’s version of Louie Louie. How although it was one of the simplest traditional chord structures used in rock music – A to D to E to D and start again and no shifting until you decided the song has ended. But what made Louie Louie different to all other rock songs that may have used this chord structure was the E in question was not a Major chord, not even one with a flattened 7th, it was a Minor, maybe even a Minor 7th. This is what Julian told me, and I remembered correcting the way I was playing it, from then on, even though the E Minor always sounded strange. Exotic strange.

Was that the song we were all playing in the photograph?

Then I remembered something else. I had always wanted to play Paint It Black by the Stones in a live band situation. There is no way we could have played it with Jayne Casey singing it. Jayne being the singer and front person of Big In Japan. Jayne would not have had the voice or temperament and anyway we only played our own songs.

And then I remembered us playing Paint It Black. And how brilliantly Ian Broudie could play the riff. And the commanding presence Pete Burns had over the vocals. And Budgie’s pounding on the drums.

Had Julian Cope’s rift with Pete Wylie - and the failure of the petition for Big In Japan to split - caused Julian to have other plans? Julian had become friendly, he had a totally different musical perspective to what we collectively had in Big In Japan. His musical perspective was very refreshing. Our perspective had been filtered through The Beatles, The Monkees, filtered again through our idea of Andy Warhol’s Factory. Julian’s perspective was all these American bands from the 1960s that I had never heard of like The Seeds, Red Crayola and The 13th Floor Elevators.

However back to the photograph and what was going on and why. I am now remembering Julian orchestrating this performance. But not in some cynical, string pulling way, but in a let’s-have-some-fun sort of way. But was he trying to move in?

We all knew that Pete Burns would be, could be, should be a brilliant frontman. He had it all – the looks, the attitude, the presence. We had sacked our bass player, Holly. Julian would have known how great Budgie was as we had stolen him from The Nova Mob. Budgie, Ian Broudie and myself were a solid band that could play tight and fast and on time. Whatever you may have read about us, we were the tightest band in all of the North West. Was this Julian making his move? If he was on bass and Pete Burns was out in front, it was bound to happen.

But that is just conjecture. We all loved Jayne, our frontwoman. Pete Burns loved Jayne. Julian Cope loved Jayne. All of Liverpool loved Jayne. And we all still do. She is our collective mother or at least the caring big sister we never had. Or the wayward auntie. She was the one we could all go to. And she still is. She is the leader of the gang.

So in the photograph we are playing Paint It Black, in Eric’s, sometime in the spring of 1978. Things are happening and things are changing.

A couple of months later we knocked Big In Japan on the head, but before we had played our farewell gig at Eric’s. And before the idea of The Zoo, as in Zoo Records, started to evolve and become a reality.

I have just remembered something else...

Pete Burns and I shared a bus ride back towards L8, or maybe Sefton Park way, but out of town, back to our respective living quarters. And we discussed future plans. We discussed the idea of forming a band together, as I am sure others must have discussed with him. This was a serious discussion. Pete was not the Pete of legend. There were no quips and one-liner putdowns. This was the real Pete. Or maybe one of the many real Petes, because we are all many.

But nothing happened, or Zoo happened and a backwater of rock ‘n’ roll history followed its course.

Pete Frame came to Liverpool and made his Rock Family Tree about all of us. Tucked away is the following paragraph that I have just read and maybe have not read for 36 years:

"Pete Burns is a strange character – probably the most bizarre fucker on Merseyside: a psychedelic Sitting Bull with rings in his nose, a cosmetic blitzkrieg of eye shadow and rouge, cascades of elaborate ear-rings, several pounds of beads and bones hanging around his neck, and a tonsorial superstructure like a rasta Tony Curtis modified by 5,000 vaults of live wire up his anus."

And just for the sake of historical clarity a "Tony Curtis" is a haircut.

THE years move on and times shift and the centre does not hold. It was March, 1985, I had a very small office in the middle of Soho, just off Wardour Street. I was an A&R consultant for a major record company. Thus I was working for the man.

This was not how it was supposed to be. This is not what I had hoped or even planned – not that I had ever planned anything.

It was just gone ten in the morning and I walked into my office and sitting on the chair, waiting for me, was Pete. But no, not Pete Wylie, or Pete De Freitas, or Pete Frame, or even Pete Burns. Or even Pete from the Libertines, as he had not been invented yet.

This was Pete Townshend.

By the time I had turned 17 I had seen every living rock act that history deemed were… anyway I had seen The Stones, Hendrix, The Doors, Zeppelin, Floyd, Dylan and all the other ones and they had all been disappointing, I had walked away from them all thinking: Is that it? Is that all there is?

If that's all there is, my friends Then let's keep dancing

And that is what I thought the first time I saw The Who, in 1969. But the second time I saw The Who, in the summer of 1970, they were everything that The Who should have been. Not that I was ever bothered about buying records by The Who. But Pete Townshend was, and still is ,the only live rock guitarist that had ever delivered for me as a teenage boy. I might have wanted to play like Peter Green, but it was Pete Townshend who made me want to smash the world up. Or at least my bedroom.

And here he was sitting in my office, unannounced and waiting for me. Did he want to smash my upright piano – it would have been a pleasure. The, I am not worthy line, in Wayne’s World Two, must have been based on this very moment. What do you offer a rock god? A cup of tea? A mug of Camp coffee?

But Pete was not bothered by any of that. He didn’t want to talk about the best way to smash up a guitar, or how old is the old before which you should die.

He wanted to talk about books.

Pete Townshend kept talking... he told me whatever it was that I was involved with in Liverpool was over

Pete Townshend was now Faber & Faber’s celebrated editor at large. Pete Townshend thought I should write a book about the whole thing I had been part of in Liverpool, in the late 1970s. Pete Townshend knew who I was. He knew about Eric’s and he knew about Zoo. Pete Townshend was talking to me. This was the same Pete Townshend who…. And… What can you say…? What has he not seen…? What offering should I give him? I am definitely not worthy! Over and over again in my head.

But Pete Townshend kept talking, he was not listening to what was going on in my head. He told me whatever it was I was involved with in Liverpool was over. Scenes do not last for that long; that whatever bands came out of that scene had now run their course, had delivered whatever they were going to deliver. And the best thing I could do was take stock: look back, write about it all. Write about it now before I forgot about it all.

And I was the person to do the writing. I should start writing that very day. Walk out of this record company and start writing now. And next week send him everything I had written. And do that every week until I had nothing left to write. And then we would get together and pull apart what I had written and he would help me then try and pull it back together again in a way people would want to read. And he told me it had to be me. No one else could do it.

This was Pete Townshend talking to me. Pete Townshend from The Who. Not the one that nearly married Princess Margaret. Or any other Peter Townshend. The real one. The one from The Who.

I tried to challenge him. I tried to ask why he continued to do music, if not The Who stuff, then his own stuff. If he believed all of what he was telling me, he should have quit making music back in the early 1970s. I held back from saying that nobody listened to his own albums anyway.

He tried to explain. He felt he had a duty to carry on making records for a small group of people in the USA who seem to need what he did. If it was just down to him, he would stop today and just get on with writing books.

Then he shook my hand and told me to send what I had written by this time next week.

And that was that – Pete Townshend was gone. I have never heard from him since, or for that matter seen The Who play live since or bought any of his records. But those 40 minutes he spent in my office have had a long and lasting impact on me. Even if I never sent him anything I wrote.

So, after composing myself, I walked out of the building and went to the café on Berwick Street which I used regularly when I wanted to disappear. I got my notebook and pen out my bag and I thought.

Pete Townsend was right. Everyone from my class of 76/77 in Liverpool had done whatever they were going to do. The Teardrops had imploded, Ocean Rain by The Bunnymen was obviously going to be their high point. Pete Wylie had done his Story Of The Blues. Holly Johnson and Paul Rutherford had trounced us all with the Frankie hits, but even they were over. Jayne had left the building for a better building, Budgie had joined Banshees and Broudie was a record producer down in London. As for Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark…

There was only Pete Burns left and it seemed that I had been wrong when I thought back in ’78 he was going to be the one. Pete Burns had tried, but to no avail. Every record he had made had sounded shite and did nothing. I had been wrong.

It was time I stopped wasting mine and everybody else’s time trying to be interested in bands that were never going to do anything or go anywhere. I had even signed some of these bands to this major label, knowing full well they were not going to amount to anything.

One of these bands was called Brilliant. They were managed by Dave Balfe. He was the only reason I signed them. In reality they were another turgid London band. Their only point of interest was they were a band with two bass players – I mean, who needs two bass players?

Then, just as I was about to start my book about those Liverpool years – the opening page was going to be my resignation letter to the music business – a record comes on the café radio.

I recognise the voice. And the record is a record, if not of genius then one of marked distinction. It is the voice of Pete Burns and the record is You Spin Me Round (Like a Record). This is the first time I had heard it.

This is the record that Pete should have always made. It had ditched all pretensions of rock or goth or any sort of guitar shit. And it did not need any of the glorious pomp of the Frankie records. This was just a pure pop dance record, with no shit or poetry or pretensions or… Anyway this is what pop music should be, could be, can be. And it is the voice of Pete Burns telling us all that.

You spin me right round, baby Right round like a record, baby Right round round round You spin me right round, baby Right round like a record, baby Right round round round

Over and over and over and over again. And in this café in the middle of Soho, it sounded like the best record in the world at that very point in time.

I never started the book, didn’t even get the resignation letter done. And nor did I finish off the cheese omelette, chips and beans I had ordered. I headed straight back to my office so that I could find out more about this record and how Pete Burns had made it.

When I got back to the office, there was a man sitting in the chair Pete Townshend had been sitting in only 30 minutes earlier. He was neither a rock god or anybody that I had ever met before. If he actually introduced himself in any sort of polite way, I am not sure, before launching into a whole tirade of reasons why I should hire him as a producer for any of my second rate acts that needed to have a hit.

He could do me a deal on using his studio at the same time and it didn’t matter if my second rate bands could hardly play because his lads would play all the music on the records and it would be a hit and the kids would love it and he knew what the kids were dancing to. And if it wasn’t a hit here in the UK it would be a hit in France or Norway or somewhere else and they could start tomorrow. And had I got anything to play him?

“What did you say your name was?” I asked when I could get a word in.

“Pete Waterman.”

“And what hit records have you produced already?”

“You Spin Me Round by Dead or Alive.”

“What? That record that Pete Burns sings on, that I have just heard in the café?”

“Yes and every other café and every club and on every radio station in the country. That record is an all time classic and it will be number one next week, or the week after or maybe the week after that. And if it is not number one here it will be number one in France or Norway or…”

The conversation took twists and turns and provocations were leapt over and we were talking about Betty Wright playing the Locarno in Coventry, circa early 1975, where I was in the audience and this Pete Waterman was the DJ. But wherever the conversation went it always came back to this Pete Waterman telling me he knew what the kids wanted to dance to and what records they would ask for and what records they would buy on a Saturday morning. And you could keep your art and your shit and your reviews in rock papers and your supposed… because all of that was crap and had nothing to do with… And had I got any bands that needed a hit? And…

As it happened I had a band that needed a hit and they were shit.

I played this Pete Waterman the first single we had released by Brilliant. He told me to sack the band but keep the singer and he had just the song for her. It would be a cover version of It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World by James Brown, but done totally different, so it would be like a feminist anthem.

How this might work I had no idea, but it surely was a sign of vision if he thought this song could be sung by a woman, a modern woman, an intelligent woman. But anyway…

I told him I could not sack the band. And after talking with Dave Balfe on the phone a compromise was arrived at. We keep the singer but also the bass player, as he had formed the band and had vision, and the guitarist because “he was good at artwork and could play like Jimmy Page”.

Two weeks later You Spin Me Around was at number one, not only in the UK but in loads of other countries if not France and Norway.

And two weeks after that Brilliant were down in this Pete Waterman’s studio in South London. And I didn’t resign from the music business or whatever, and I didn’t start that book that Pete Townshend told me to.

The way Pete Waterman and his boys, Mike and Matt, worked was a total revelation to us – nothing to them was sacred. Everything could be scrapped or changed. Nothing could stop them.

That said, It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World, which this Pete Waterman and his boys made with Brilliant, never made the Top 40 in France or Norway let alone the UK. Nor did the subsequent album that they recorded with him. It was all shit.

But something else did, very much, happen. The bass player out of Brilliant was called Youth, he started to learn how to really produce records and has been producing records ever since, from The Verve to Kate Bush.

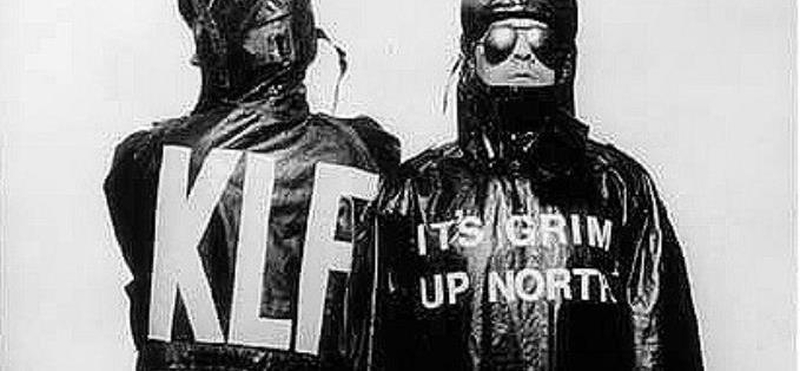

Dave Balfe learned what a hit smelled like, and that sense of smell which he developed was a major part in his success with Blur. As for the guitarist in Brilliant, who could draw and wanted to play like Jimmy Page, that was Jimmy Cauty. It was where he and I got to know each other.

What Jimmy and I both learned in those few months, in Pete Waterman’s studio, we were then able to use and abuse in our subsequent quest as The KLF and all the other names we chose to use.

You might hate the subsequent records Pete Waterman made with the likes of Kylie and Jason and the rest. But if Pete Burns had not made You Spin Me Around with Pete Waterman, my journey would have gone in a totally different direction.

And I did resign from it all and left music behind, so as to get on with writing just as Pete Townshend told me to. And the world turned and the winter solstice passed and the sun rose and it was January 1987 and the question had to be asked:

‘What The Fuck Is Going On?’

On Thursday - as in the Thursday after Pete Burns died and not some Thursday back in the mid 1980s - I was contacted via text by a friend of mine. An old friend. A very good friend. A friend who I had known from that time in London. A friend who had been very much part of the early 1980s London scene of Boy George and all that Blitz crowd thing. She wanted to know if I knew, and how I felt, about the passing of Pete Burns. And I told her how it affected me more, far more than I was expecting.

She was surprised: surely he was just a one hit wonder, with barbed tongue and too much attitude?

There is no doubt Pete Burns was basically a one hit wonder and his wit was acerbic. But my mind was focused.

That trashy one hit can leave more legacy of standing and lasting artistic merit than a whole lifelong career of well received long playing albums.

I had, and still have, no interest in what Pete Burns became for viewers of reality TV or the readers of tabloid papers.

Pete Burns may have been the last out of our class of Aunt Twackies and O’Halligan’s Parlour and the Liverpool School and Probe and Eric’s and that manhole cover I keep going on about; the last of that class to make a record that clawed its way into the top 10 and then the number one spot and into…

Nevertheless, if it was not for hearing that record in that café, in Berwick Street, between being confronted by Pete Townshend and Pete Waterman on a March morning in 1985, I may have never thought it worth trying again to use pop music as a medium to make art, great or otherwise.

And You Spin Me Round (Like A Record), by Dead or Alive, is great art. As great a work of art as anything else produced in the 20th century. And if you can’t see, hear or understand that, then there is something sorely missing in your imagination.

Now roll over Chuck Berry and tell E. H. Gombrich the news.

******

Before reading through everything that I have written above and trying to make sense of it, I will look at the photo again and see what else I might be able to remember.

Nothing much. I don’t even know who took the photo. Most probably Hilary Steele, she was always taking photos. And I liked the photos she took. I like this photo.

But I do know while that photo was being taken, while we were all on that stage in Eric’s blasting out our version of Paint It Black, or whatever it was, some other things were going on in Liverpool.

Somewhere there would have been a brooding Pete Wylie, planning his next Wah! move to outmanoeuvre Copey.

There would have been Mac backcombing his hair in the mirror, knowing he had the greatest voice in all of Merseyside if not the universe.

There would have been Holly, with his voice and his songs that none of us had ever heard, knowing that he knew what was needed and how it should sound and where it should go.

And Jayne will have been standing a few feet away goading us all on.

The world moves fast and within a very short time we would all be over and done with. Part of a fading history, not even of an interest to the likes of Mojo. Not even up there with the Blitz crowd of new romantics, or the synth pop wave, or the shoe gazers, or those that signed to Creation, or the Madchester gang, or the ravers, or Britpop bands or the end-of-pier indie boys and girls hoping for one last hurrah, when guitars and their jangle no longer meant anything to anybody.

I had not spoken to Pete Burns since sometime in those very early 1980s. We had little in common.

But we were in the same trench when our officer blew the whistle and it was time to go over the top and meet whatever the enemy had for us.

Pete Burns may have been the last over the top, but he was the first to fall.

Rest in peace, Pete, and on this Remembrance Sunday we that are left to grow even older will remember you.