YOU won't find much about Kif Higgins in the archives of our local media. No Wiki entry or anything much in the way of an authorised biography - digital or otherwise.

Perhaps that's how he would have had it. For Kif Higgins, artist, promoter, musician, community activist, was not the sort to stand on ceremony. He just got on with the job.

'Earthbeat was a fantastic collective of beautiful, artistic and creative people who brought their individual influences and talents together to provide some amazing gigs and public art events to an otherwise very dull city'

Yet listening to the talk of the town this week, it is hard to believe that the whole city didn't know him.

“He was a person who went out and did things, he made things happen,” says Jayne Casey, lifelong ally, friend, and mother of the eldest of his three children.

"The job” was making a difference, and he and his like-minded band of brothers and sisters remained completely independent from political or artistic control.

Kif Higgins grew up on the streets of Granby in the 1960s. By the late 1970s he had crossed the line out of L8 - a time when the idea of a wider multiculturalism, for Liverpool, existed only on the far flung shores of academia.

Hardman Street: a Sunday afternoon in 1977. It was the Hope Street Festival and Higgins and pals, out on a stroll, just happened to pass the racket that was Big In Japan, performing only their second ever gig on a Baltimore Street stage.

He stopped to watch. It was, after all, something of a spectacle. What had started out as a gig was rapidly unfolding into a police incident, recalls front-person Casey, after nearby residents had snapped and called the local constabulary.

She was, she admits, never one to go quietly into a van, especially in possession of a live mic, and the ensuing fracas made an impression on the 20-year-old Rastafarian.

A week later Higgins was down in Mathew Street looking for more. He found it. And them. And Eric's – the only “white” club outside London pumping out reggae. And he found a new set of possibilities.

“We were reinventing our view of the world,” says Jayne, “and Kif was too. He immediately fell in with that.”

Following the 1981 riots, which introduced Toxteth to the world, it was Higgins who first gave credence to the notion that some damage can be healed through artistic endeavour.

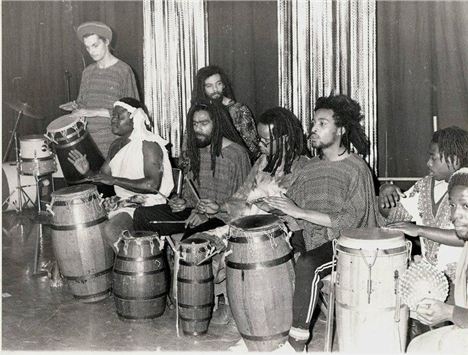

Exchange Flags shenanigansWhile Michael Heseltine was planting trees on Princes Avenue, Higgins was sowing seeds of a different kind in the scorched earth of his streets. He set up the African drum and dance collective Delado which went into schools and gave the angry, young and dispossessed a different focus: an articulation, a sense of spirituality and an idea of who they were.

Exchange Flags shenanigansWhile Michael Heseltine was planting trees on Princes Avenue, Higgins was sowing seeds of a different kind in the scorched earth of his streets. He set up the African drum and dance collective Delado which went into schools and gave the angry, young and dispossessed a different focus: an articulation, a sense of spirituality and an idea of who they were.

“It had a massive impact on the kids in L8,” says Jayne. “So many of them grew up with the confidence to carve themselves positions in the system. They were able to make a real difference too. That's his legacy.”

By the mid 1980s, Higgins had set up HQ on the upper floors of a Bold Street building. Nobody lived in the city centre then, there was certainly no Ropewalks – and most of those who had created the post-punk buzz had swarmed off to the London hive.

Even the Larks In The Park team had abandoned the Sefton Park bandstand – previously the focus of so much summer love.

With the city soundtrack careering towards Rick Astley and the Reynolds Girls, Higgins stepped in with an incendiary: Earthbeat, which would rally the next wave “too young for Eric's”.

Earthbeat also took place on the bandstand - over the late 1980s and early 1990s - and from the off was auspicious. The first one, in 1987, saw Pulp, The Stone Roses and The La's sharing the same stage. For free. But it was never a straight bat and there were plenty of avant garde acts like The Goat People to sate those hungry for inspiration.

Paul Fitzgerald, who runs the Liverpool One Bridewell pub, was in the band Eat My Dog. He recalls: “Earthbeat was a fantastic collective of beautiful, artistic and creative people who brought their individual influences and talents together to provide some amazing gigs and public art events to an otherwise very dull city. Some light. Some colour. Amazing nights and days, which will remain in my heart and my mind for ever.”

Higgins drew his own crowd easily, because, says Jayne, “he was charismatic, elegant and co-ordinated”. Along with performance artist Jonathan Swain and other activists who went under the name the Stress Block, Higgins oversaw large-scale happenings such as the Urban Vimbuza.

It was the height of the Thatcher years and the collective focused on controversial and confrontational subjects.

Another collaborator, Simon Crab, wrote: “Because they were held in Liverpool, a long way from anywhere else, it meant they were ignored by the rest of the country.

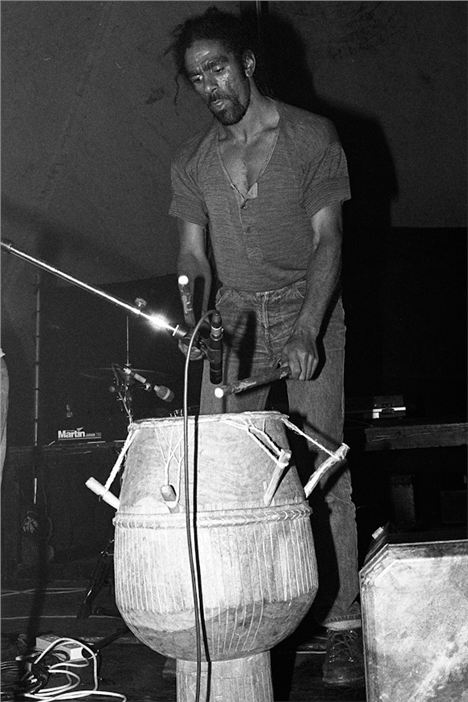

Kif At Earthbeat - Picture By Mark McNulty

Kif At Earthbeat - Picture By Mark McNulty

“Vimbuza scrutinised racism, capitalism, slavery, terrorism, violence, hypocrisy and threw it back in the face of an ever-widening consumer society. The spectacle succeeded because it drew on genuine anger and spontaneity.”

Such as Death By Free Enterprise.

“On Saturday the fourth of June 1988, as the sun set on the Bluecoat courtyard in central Liverpool there occurred an hour long incident,” Crab writes here. “A monumental barrage of sound, light, image, daring, dance, fire, music, speech and performance. A spectacle based on the African Vimbuza ritual, designed to strengthen us all in the fight against those evil and negative spirits that have polluted the world sporting the brand names of Colonialism, Market Forces and Incentive, but all the time disguising the real sponsors: Greed and Negligence.”

It was powerful, heady stuff and there was more to follow: at St George's Hall Plateau, we were all treated to another “Visual Stress”: This time screeching armoured cars, African dancers, manacles, slaves and Artemy Troitsky (Russian rock journalist, author of several books, one time boss of Playboy Russia and head of MTV Russia) on the top of a 50 metre high column declaring sections of Das Kapital in Russian through a megaphone.

With "Sold Down The River" by Nina Edge

With "Sold Down The River" by Nina Edge

When he died last weekend, at the age of 54, from lung and secondary brain cancer, Higgins had amassed a considerable body of his own visual art, so far unseen by the public, and had become an avid collector of African artefacts. He liked ritual, say those who knew him, and symmetry - which drew him to create Ethiopian-coptic shrines.

He was also described as a dedicated father and leaves partner Natalie Gledhill, two grown up sons – Ra and Sunni – and a 10-year-old daughter, Ayla.

Kif Higgins, his deeds and his projects, shone like a beacon on the horizon of the restless and yet were massively off the radar of the establishment who might, might, have funded some of it, if they had, indeed, got it; a heavy double-edged sword to carry for all but the bravest outsider.

His were shift-changing movements that have endured down the years purely in the heads, memories, chat and the faded snaps of a generation who witnessed them.

This, of course, may now change.

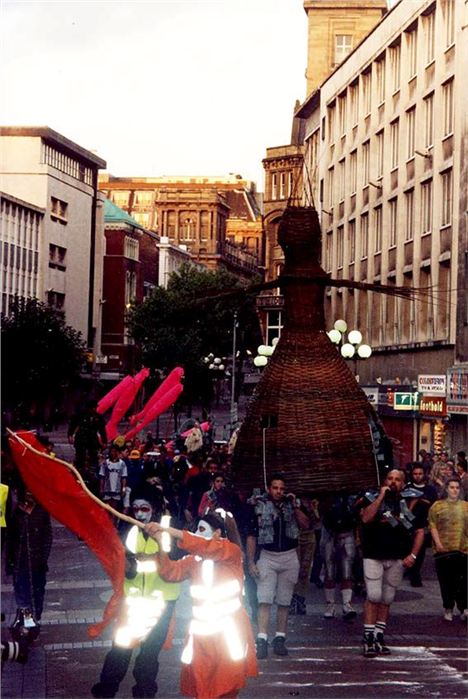

2011, Bold Street. Picture by Saul Hughes

2011, Bold Street. Picture by Saul Hughes

*The funeral of Kif Higgins takes place on Friday June 1, 2pm, at the Unitarian Church 57 Ullet Road, Sefton Park, Liverpool L17 2AA, followed by Springwood at 3:30pm. Following onto The Picket, 61 Jordan Street L1 0BW, 4:00pm.