It was revealed this week that developers paid £4.9m for Josephine Butler House, home of the UK's first Radium Institue, on the corner of Hope St and Myrtle St. Now it is set to be demolished and a 16-space car park laid in its place (that's £306k a space). Here, Hilary Burrage gives her appraisal.

THERE weren't many grand ladies who chose to spend part of their lives ministering to the needy, in the workhouses, in Josephine Butler's day. But she was one of them, protecting - and fighting for - the health and education rights of Victorian society's most vulnerable.

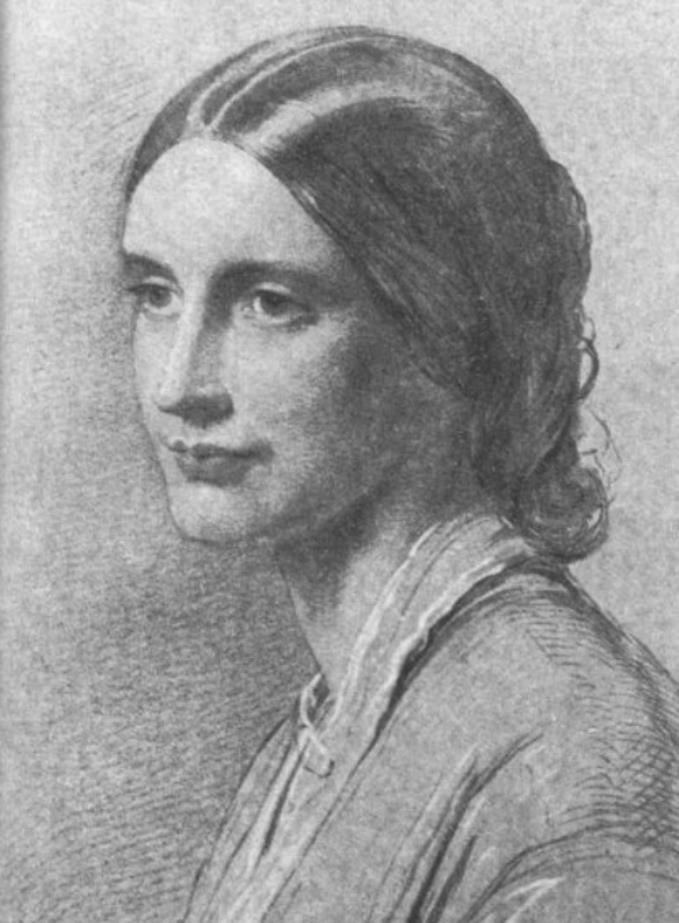

However, slowly (and arguably too late) the name of this Liverpool College headmaster's wife, who was once described as “the most distinguished woman of the 19th century", is permeating the modern civic psyche of her home town. But for all the wrong reasons.

Josephine Butler has been remembered in archives and institutions around the UK and beyond; her achievements have not been totally lost on Liverpool either. There is a window in her memory in the Anglican Cathedral; the University of Liverpool has a named archive; the Hope Street / Mount Street 'Suitcases' commemorate her, and, until now, Liverpool John Moores University has also acknowledged our collective debt to her reforming zeal, naming one of its properties in Myrtle Street for her.

But recently things have changed.

Before

BeforeMore than a year ago, LJMU came to a £10m commercial arrangement with Maghull Properties which saw Josephine Butler House and three other buildings in the Hope Street Quarter, including the the Hahnemann Building, site of the first homoeopathic hospital, and the School of Art, transferred to the Maghull portfolio.

There was, at the time, considerable public concern about the plans which Maghull then presented for agreement by Liverpool city council - plans which included demolition of the LJMU Josephine Butler House.

The small patch of land on which it stands, at the corner of Hope Street and Myrtle Street, is the only non-conservation site in the Hope Street quarter - a surprise, not only because several organisations have been repeatedly urging the city council to rectify this oversight for years, but even more so because Josephine Butler House was, before its academic use, the home of the first Radium Institute in the UK.

Worse, however, was to come.

When the Maghull demolition plans were lodged, several bodies and individuals launched objections and a move was made to have Josephine Butler House listed (it would have been protected without further ado, if within the conservation area), or the permissions for the development refused. Liverpool Riverside MP Louise Ellman called on the council to put a preservation notice on the building.

None of these actions was achieved.

Hammer horror

Hammer horrorInstead, before any of this could happen, and a few days before a city council planning committee site visit, scaffolding was erected around JB House, and hammers were applied to almost all the frontage of this, until then, quite useable building.

Amazingly, the city council - who might well be judged to have been cocked a snook by these actions - then capitulated to the planning request to demolish it, perhaps because by now the building was in a state of disrepair.

And this is where, a year later, things still “stand”. The tarpaulins have fallen from the building and the scaffolding has gone, leaving a huge, gaping, sorry and derelict building, previously a very decent example of the construction of its time, at the heart of Hope Street.

In the latest move, the apparently-credit-crunched owners, Maghull, have succeeded in another application to the city council - to use the land it would acquire by razing Josephine Butler House, not to create a commercial, “boutique hotel” development as originally intended, but to lay... a 16-place car park.

Residents of the adjacent Symphony apartments, every visitor to the Philharmonic Hall, and, crucially, the very many travellers who every day pass through this prime gateway to our cathedrals, universities and city centre, none of them can miss the grim evidence of civic neglect which the shell of Josephine Butler House now presents.

It would be fair to say sympathy is limited for those who now wish to “develop” the Josephine Butler House site, credit crunch or not. Nor is there much evidence of sympathy for the city council, which gave the permissions which have allowed this situation to develop.

Why did no one listen to the many concerned voices? Perhaps some of them now rue overriding the deep concerns of many ordinary people and not “just” the usual conservation suspects.

The Josephine Butler House saga is not over. Many still wish fervently that it can be restored to good, sustainable use. How this might be achieved lies with the city council and commercial stakeholders in the building.

The shroud goes on

The shroud goes onBut that is not all. Increasingly, and especially following the critial article by Ed Vulliamy in the Observer of 20 March, the eye of those further afield is also upon us.

What is happening to the memory of Josephine Butler and the building named for her is important for Liverpool, a city which claims to be restoring its civic pride and wider reputation.

Not everyone as yet knows about Hope Street's association with Josephine Butler, but most are aware of the connection between another of Liverpool's citizens, John Lennon, and the School of Art which he attended, a building bought and leased back by Maghull to LMJU until 2011.

Now might be a good time to reflect on how 'developments' may look in the longer term, if we do not take account either of the buildings which define the Hope Street area, or the sons and daughters of the city who have conducted their business for more than a century in this uniquely special quarter.

Past notes: Josephine Butler

Having relocated to Liverpool with her husband, the scholar and cleric George Butler, when he became head teacher of Liverpool College in 1866,Josephine Butler (1828-1906) made Liverpool the family home for her three sons, her husband and herself.

Sadly, this family had originally comprised four children; but shortly before they came to Liverpool the six-year-old daughter, Eva, died in an accident. This tragic turn led Josephine - always the owner of a stirring social conscience - to immerse herself even more in helping others, perhaps as a way of deadening her own pain.

Any consolation for Josephine cannot however have been as immense as it wasfor those whom she sought to protect and champion: women who had turned indesperation to prostitution, women who yearned for higher education, andnumerous others besides. There were not many grand ladies in Liverpool whospent a part of their lives ministering to substantive effect in theworkhouse.

And from these earnest endeavours emerged the image of Josephine Butler towhich later social reformers turn, that of the social pioneer whom thesuffragette Millicent Fawcett herself described as “the most distinguishedwoman of the 19th century".